Bishop Juan Gerardi was savagely murdered on April 26, 1998, two days after presenting the Recovery of Historical Memory Project (REMHI), the Guatemalan Catholic Church’s report recounting the atrocities committed by the Guatemalan Army during its 36-year armed conflict. The 78-year old bishop, who led the unprecedented effort of collecting war testimonies, was bludgeoned in the head and face with a concrete slab outside his parish home in Guatemala City’s Zona 1. A grief-stricken nation mourned his loss as a direct affront to an incipient democracy, still unfamiliar with justice after a blanket amnesty left all those involved in civil war-era crimes unpunished.

A crime thriller dealing with the series of events that unfolded following Gerardi’s assassination, Francisco Goldman’s 2008 book The Art of Political Murder encapsulates the postconflict climate in Guatemala by intimately focusing on the brave Guatemalans who invested over seven years in the prosecutorial efforts seeking justice. A new HBO documentary by the same name, directed by Paul Taylor, has not only received accolades, but an online effervescence also has brought this incredible story to a new and wider audience. “I am really amazed by the reception I am seeing,” Francisco Goldman told me. “Young people have been awakened to what the case represents in the past and its relevance now.”

The powerful visual elements of the documentary allow for many vivid portraits of characters, rather than just sketches of individuals trying to do their jobs. This offers necessary depth for understanding the complex network interplaying in the Gerardi case. The documentary chronicles not only the police investigation, but also the more fascinating investigation into the investigation. Beyond carefully describing the anatomy of a crime and the circus that ensued in an attempt to cover it up, The Art of Political Murder opens a window to a misunderstood country that is again flirting with authoritarianism by continuing to violate the rule of law.

Among the many interviewees are key members of Gerardi’s organization, the Catholic Church's Human Rights Office (ODHA), including director Ronalth Ochaeta and investigators Rodrigo Salvadó, Arturo Aguilar, and Fernando Penados. Also featured are Edgar Gutiérrez, director of the REMHI, who worked closely with Gerardi; prominent human rights activist Helen Mack, who remains an influential figure in the contemporary public sphere in Guatemala; former Guatemalan Public Ministry special prosecutors Otto Ardón and Leopoldo Zeissig; and Claudia Méndez Arriaza, a journalist “who was there throughout all the Gerardi hearings,” as Goldman noted.

Now, as popular discontent is on full display with anti-government protests reaching their fourth consecutive week, the documentary arrives at a pivotal moment in Guatemala. Goldman reflects on the contemporary effects of Gerardi’s case in a country stunned by decades of political violence. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Vaclav Masek: The brutality of Gerardi’s murder was such an obvious response to the REMHI human rights report that the military was automatically blamed by the general public. Many Guatemalans understood the message sent by the killing was that the army did not care about the REMHI and the ongoing Peace. And that no one, even including the most public-facing figures, was safe from their reach. Later, alternative theories were created to provide believable alibis and smear Gerardi by questioning his sexual orientation. Police investigators even went so far as to arrest Bishop Gerardi’s dog, Balú. What does it say about the connection between the three most powerful actors in Guatemala—the state, the Church, and the military?

Francisco Goldman: The Gerardi case was planned meticulously by the Guatemalan military; they took the lead in the planning as a work of theater. That’s why the book is called The Art of Political Murder. This murder could never have gone forward without a lot of very high-up people in power then—very powerful war veterans. This crime could be done to say that war crimes trials and this type of human rights work would not be allowed in the future. I think they did not have much trouble bringing the political sector along with it.

The Church was in a different position; it was no longer under a right-wing cardinal [Mario Casariego]. At the time of Gerardi’s death, there was a more moderate archbishop, Próspero Penados, that became the emblem of an elitist clergy in the capital. When the army pulled off this crime against Gerardi, they had no reason to ever suspect that they would be investigated by police. The army even knew what prosecutor was going to be assigned to the case before the assassination took place. They never foresaw that the whole script was that Bishop Gerardi’s human rights office [ODHA] had very strong support from Archbishop Penados and even by the man who replaced Bishop Gerardi, who curiously was Efraín Ríos Montt’s brother, Mario Enrique Ríos Montt.

To live close to this case was to endure waves of disinformation. Everyone could become easily confused if they were watching it from outside. I had the incredibly good fortune to be very close to the people who were investigating, even befriending the prosecutors like Rodrigo [Salvadó] and Arturo [Aguilar].

For example, I was there when the taxi driver agreed to give his testimony that would later send him into exile in Canada. I remember he started crying and saying, “Why do we have to leave the country if we are doing something good?” So later, when all the fake propaganda started that attempted to enforce counternarratives pushed by military intelligence, I was able to identify the shortcomings in their flawed arguments. Unfortunately, back then, even respectable Guatemalan journalists were replicating these narratives because they were not inside the case.

VM: Those interviewed include confidants of the bishop, prosecutors and journalists involved in the case, and a homeless man whose late-inning revelations will have viewers sitting up straight in their chairs. How has your relationship with the characters and to the story changed in the last two decades?

FG: This was a nine-year case. Having gone through that with all of them made us incredibly close, making for life-long friendships. Even among them, there have been some falling outs because of certain political choices they made later. What is remarkable is that many of them went out to play important roles in Guatemala to this day.

For pulling the book together, the most important thing I did as a journalist was find out where Leopoldo Zeissig was in exile. Zeissig was the man who figured out the case. I spent three days in Ecuador, talking with him in my attempt to piece together the moving parts in the investigation. Zeissig would come back to Guatemala to become a prosecutor for the International Commission Against Corruption and Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). Arturo Aguilar became a prosecutor for CICIG and for the Public Ministry under [former Attorney General] Claudia Paz y Paz.

VM: I wanted to ask you specifically about the role of prosecutors in a country where impunity has reigned supreme. I had the honor to interview Judge Yassmín Barrios for NACLA last year. Judge Barrios presided over some of the most important cases in Guatemala, including the historic genocide trial against Efraín Ríos Montt. Can individuals yield enough power to fight the structures that prevent change from happening?

FG: People approach this inquiry through legal abstractions, like fighting for justice in a democracy. But I always like to remind everyone that this is a profoundly human story. We forget that to make these things happen, we need human beings. If this murder happens in another time, maybe years before or later, we do not have the same constellation of people in place. And the case would never go forward. It takes extraordinary courage, conviction, and camaraderie for this to happen. Nobody becomes a prosecutor because they want to eat shit.

VM: Especially not a prosecutor in Guatemala!

FG: Exactly. They might have to look the other way and bend to the power of corruption to keep their families alive. Before Leopoldo Zeissig was assigned as the third prosecutor in the Gerardi case, Celvin Galindo, his predecessor, was doing a fine job. It was completely normal for Galindo, once the threats got more intense and repetitive, to decide it was not worth it for him and his family to take the risk, so he left the country. The same with all the judges assigned before Yassmín Barrios, who left out of fear of persecution.

Leopoldo Zeissig endured the most withering, awesome, relentless number of threats when he was pushing the case until the end, including some terrifying things. When they did the routine search through Byron Lima’s prison cell, wardens found maps that illustrated all the ways in which to reach Zeissig’s house. At night, he would hear footsteps on his roof. The terror that prosecutors put up with is incredible.

VM: Is this what you want the viewers to feel when they are watching the documentary? And moreover, what do you expect the audience to take away from the story?

FG: Obviously you hope people will like it but I did not think it was going to be this widely viewed. I did not expect this commotion; I only expected the usual right-wing bots [laughs]. But the outpour of emotion and recognition on Twitter has been really incredible.

VM: Of course. My read is that Bishop Geradi’s murder has a historical significance for Guatemala and the region at large. I wanted to ask you if it's reasonable to include him in the pantheon of Latin American martyrs, perhaps on par with Bishop Oscar Romero from El Salvador.

FG: Absolutely! I think Bishop Romero’s case is different from Gerardi’s. Romero is a different kind of leader—extraordinarily great, mystical in his courage, saintly. Gerardi is saintly in a different way; his story is so human. He has a period in his career when he is in disgrace after he closes the Dioceses in Quiché and the Pope [John Paul II] yells at him, saying that the Church ought to be close to the people. Upon his return, Gerardi is denied reentry into Guatemala, and his asylum request is rejected in El Salvador. He spent four years in exile in Costa Rica, frustrated and humiliated. When he comes back to Guatemala, he really tries to make the best of it; he became a pragmatist. Gerardi becomes indispensable for Archbishop Penados as a political tactician, gaining involvement in the peace negotiations.

When Archbishop Romero was murdered, no one had even a shadow of a doubt of who did it. The Gerardi murder itself, in a way, is part of his legacy. The collusion between politicians and the army, and even journalists, is what makes it so incredibly relevant today. This was really a fight that the Church and the prosecutors waged against misinformation and falsehoods.

VM: The story you created has artfully pulled back the curtain to reveal Guatemala's sinister political scene. There is an ongoing crisis in Guatemala with structural issues—violence, corruption and impunity, and mass migration—generally tied to weak institutions that did not consolidate after the peace process. Do you reckon much has changed for Guatemalans since the Peace was signed in 1996?

FG: It is a long story. Early on, it was understood by many people that once the Cold War was over and the CIA was no longer interested in treating the military intelligence in Guatemala as its accessory that the military was going to betray the peace accords and hold on to power through existing political structures and their connection to organized crime. That’s really what the whole case was about.

One reason why the military felt so threatened by the support given to Bishop Gerardi and ODHA was because the pressure would eventually force them to give up control of military intelligence, which the peace accords called for, but of course never happened.

The only way to keep Guatemala from being a failed state is to strengthen its justice system against this fight. And that is why CICIG is so important, and why people love CICIG. The Commission grew right out of the Gerardi case and gave Guatemalans hope throughout all these years.

VM: Do you think that the dismantling of CICIG was a coordinated attack by the political elites?

FG: Yes. Narcos, political elites, corrupt Guatemalan powers trying to get in good standing with the Trump administration.

VM: Essentially, the right wingers across the hemisphere coincided in power so their mutual realization about the real threat of CICIG triggered their reaction.

FG: The Trump administration had a direct impact. For example, Marco Rubio cut funding for CICIG, even after decades of bipartisan support for a robust anti-corruption agency. Both Republicans and Democrats understood the importance of CICIG. That all collapses when [former Guatemalan president] Jimmy Morales sucks up to Trump by moving the Guatemalan embassy in Israel to Jerusalem…

VM: That and signing the so-called Safe Third Country Agreement, which was another attempt to curry favor with Washington.

FG: Exactly. Trump backed Morales in what is essentially a coup against the rule of law in Guatemala. If Trump had lasted four more years, it would have been as devastating to Guatemala as the 1954 coup.

VM: On that note, do you expect president-elect Joe Biden will bring about positive change, make it worse, or keep the status quo?

FG: He’s going to make it better. The Guatemalans who matter are in place. Biden has always been super interested in Guatemala and Central America, so I expect he will revert some of the punitive measures set in motion by the previous administration. His plan for the region has mechanisms to replace CICIG, in certain ways. You see that recently in Guatemala, with how the U.S. Embassy expressed its support for the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Corruption (FECI) just last week. FECI is the last remnant of the CICIG culture. And CICIG draws a direct line to the Gerardi case.

So prosecutors are defending democratic institutions from being captured by corrupted individuals or organizations. It is a really hard battle, but it is the battle in Guatemala.

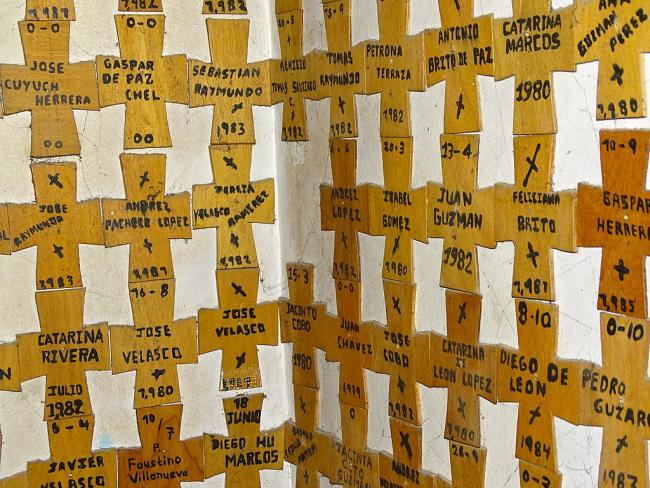

VM: Just like your book, the documentary succeeds at weaving a web in which justice appears impossibly elusive—which gives the ending all the more punch. However, the limits of impunity in Guatemala are constantly being redrawn by power brokers that operate in the political system. Are there any reasons for hope that justice will ever come to the victims of the war in Guatemala? Not necessarily for cases involving high-profile names like Geradi, but for those Indigenous communities who have been devoting themselves to seeking justice for all these years.

FG: I hope so. There are so many fronts on which they have to fight. Hopefully we’ll keep seeing these paradigmatic cases go to trial; I am sure they will. CICIG was not allowed to take up the Gerardi case, for instance, since their mandate was limited to contemporary cases. Maybe the first thing that ought to happen is strengthening the rule of law and garnering popular support to change the way Guatemalan political parties are formed and operate.

When people say, “Prosecutors are important because they go after captured democratic institutions,” the analysis must include a proposition to go after political parties. Even the way elections are organized must be questioned.

VM: To wrap things up: What do you expect the audience to take away from the documentary?

FG: Guatemala has incredible valiant people that are willing to wage this fight. In fact, they have been waging it all along, even before the Gerardi case, which represents a rare victory.

Vaclav Masek is a doctoral student in Sociology at the University of Southern California.