This piece appeared in the Fall 2021 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

April 12 is the Day of the Black Ethnic Race in Honduras. It’s a national event in which Garifuna—a Black Indigenous people of West African, Carib, and Arawak descent—are celebrated for their “contributions” to Honduran society and culture. However, on April 12, 2021, the normally festive occasion was marked by a tenor of rage. Two hundred twenty-four years after their arrival in what is today Honduras, Garifuna activists affiliated with the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH) exclaimed: ¡Basta Ya! Enough! Enough failed promises. Enough displacement from their homelands. Enough killings of Garifuna land defenders.

Almost a year had passed since four Garifuna men from Triunfo de la Cruz, including the president of the communal governing council, Snider Centeno, were forcibly disappeared. Dressed in police uniforms, the assailants entered the community before dawn, detained the victims at gunpoint, and forced them into unmarked vehicles. They were gone without a trace. In her denouncement of the crime, OFRANEH leader Miriam Miranda implicated the state’s possible involvement, an accusation that stemmed from the government’s longstanding efforts to transform the Garifuna community Triunfo de la Cruz and the Tela Bay region into a glittering Cancún-esque tourist destination. The growing list of assassinations of Indigenous land and environmental activists across Honduras—perhaps most notably the 2016 murder of Goldman Environmental Prize winner Berta Cáceres—lends credence to Miranda’s concerns. Reporting by journalist Nina Lakhani revealed that Cáceres topped a military hit list ahead of her murder, and Garifuna leaders take the threat of similarly targeted attacks very seriously.

The kidnappings of Snider Centeno, Suami Aparicio Mejía, Milton Joel Martínez, and Gerardo Rochez followed on the heels of a 2015 Inter-American Court of Human Rights judgment that found the state guilty of violating Garifuna communal property rights in Triunfo de la Cruz. During the Court’s public hearing, held in May 2014, the Honduran attorney general argued that Garifuna are not an “original people”—that is, indigenous to Honduras—and thus should not be considered legitimate heirs to national territory. The negation of Garifuna Indigeneity, and the legal displacement of Blackness from the nation, is a strategy used by the state to uphold the rights of mestizo settlers and elite investors who have usurped large tracts of land within Garifuna territories, as I have written in my article “Adjudicating Indigeneity.” The state celebrates Garifuna racial and ethnic difference even as they deny it. This tension stems from the fact that Black culture is good for tourism, but Black land rights are not.

Since the Court’s ruling, attacks on community land defenders have intensified—with impunity. This failure of justice is not a coincidence; Black and Indigenous lands and labor are crucial to the accumulation of capital within Honduras and globally. As such, the marked escalation of violence against Garifuna land defenders in Honduras must be understood in relation to a larger pattern of racist violence against Black and Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas, which is crucially bound to the global resurgence of extractivism. State governments, national elites, and international investors deem the land, water, and mineral resources concentrated within Black and Indigenous territories essential inputs for the advancement of global capitalism, but in ways that show utter disdain for Black and Indigenous lives, and for all life on this planet. Writing in the 2020 volume Black and Indigenous Resistance in the Americas, edited by Juliet Hooker, the Antiracist Research and Action Network (RAIAR) has referred to the current political moment—marked by a dramatic rollback of minority rights regimes—as one of racial retrenchment.

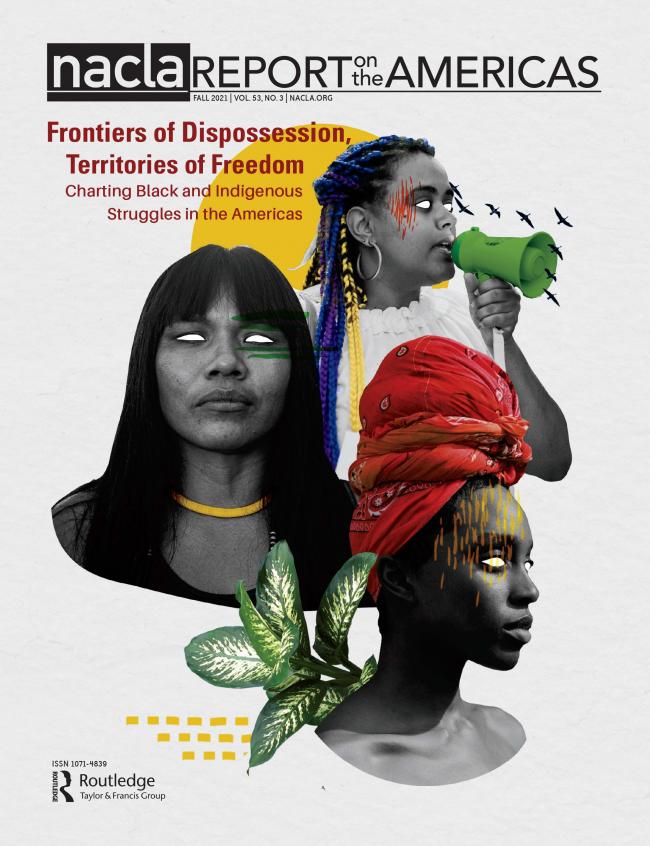

This issue of the NACLA Report brings together scholars, activists, and artists who are not only committed to documenting the catastrophe of racial capitalism, a term coined by political theorist Cedric Robinson, but also to investigating how racialism is bound to histories of “resource colonialism” (as Nick Estes puts it in this issue), mass criminalization, environmental plunder, and orchestrated tactics of erasure and dispossession. The contributors see these processes as interlinked, as are the movements and forms of life that have arisen in defiance of this death system. This issue centers the devastation and racialized effects of global capitalism, while also shedding light on the ongoing struggles of Black and Indigenous peoples for freedom, autonomy, and life.

Willful Entanglements

Romanticized notions of Black and Indigenous peoples living together in perfect harmony is a fallacy—after all, we know that enslaved Africans were held as chattel, not only by whites but also Natives and, in some cases, by freed Blacks. Historian Tiya Miles has been instrumental in bringing these stories into our political consciousness, while also recognizing that many enslaved men and women found freedom among Native peoples. Yet representations of Blackness and Indigeneity as fundamentally separate racial categories persist, violating and erasing centuries of coalitional politics, shared struggle, and cohabitation, however fraught.

What are the stakes of thinking across the silos? Or, as Roger Reeves puts it in his piece in this issue, “Why can’t we think Blackly and Natively simultaneously?” Research into the deeply entangled histories and contingent struggles of Black and Indigenous peoples past and present, beautifully captured by Miles and other scholars such as Mark Anderson and Tiffany Lebotho King, has helped to carve out new areas of inquiry. Perhaps more importantly, this emergent body of work is a testament to on the ground political and theoretical work, anti-racist struggle, and movement building.

This NACLA Report addresses a number of key themes that cut across the region, including how Black and Indigenous lands are rendered empty, or up for grabs, and how the capitalist system, predicated on the extraction of land and labor, colludes in the annihilation of life. The pillage of Indigenous and Black territories, carried out in the name of sustaining endless economic growth, has produced profound inequities and irreparable ecological destruction. Moreover, the turn to sustainable or “green” development, intended to abate raging environmental crises, such as severe drought, mega-storms, and energy meltdowns, are woefully inadequate. The contributors in this issue shed light on these processes, while also asking: how might we reimagine our shared future?

Read the rest of this article here, available open access for a limited time. View the table of contents of the issue here.

Christopher Loperena is assistant professor of Anthropology at the CUNY Graduate Center. He has served as an expert witness at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and in U.S. Immigration Court. He is completing a book titled, A Fragmented Paradise: Blackness and the Limits of Progress in Honduras.

Cover art by Mazi | @mziarte on Instagram (with images from Mídia Ninja)