Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

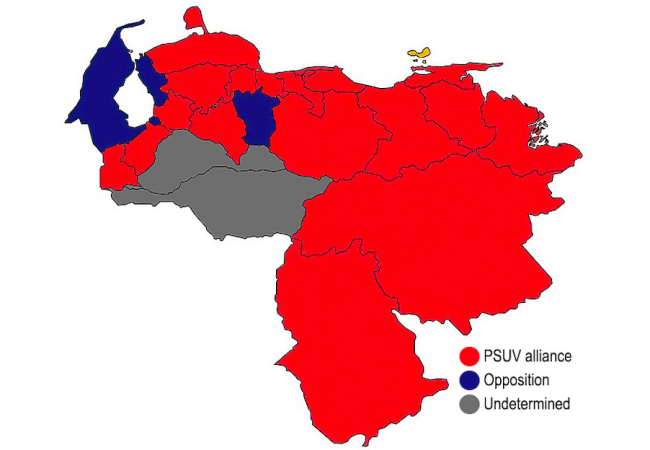

On November 21, Venezuela held regional and municipal elections. With 42.26 percent voter turnout, the PSUV won 18 of 23 states and 205 municipalities. The diverse opposition forces have secured three governorships and 117 municipalities so far. At the time of writing, two governorships remain in dispute and the results in a dozen municipalities are yet to be finalized.

The election results are a snapshot, not the feature film. These are elections in the middle of a country that is very rapidly changing. We have not had the time nor resources needed to take stock of the changes through rigorous social research. Consequently, we must interpret the election results with an understanding of how they sit at the crossroads of the country that is and the one that is emerging.

Politics often lag behind society. For at least three years, the country has been taking a turn. What some call “the collapse of the economic model” and others “the new crisis of the old development model” hints at substantial changes to the flow of daily life and social and political imaginaries.

Until now, polarization allowed the political class to coast on these realities. On the one hand, the government sold its supporters the idea that it would find a magical formula to escape the crisis. On the other hand, the opposition claimed to have its own magic formula to replace the government in the short term.

Both sides came up against reality. The government—completely isolated globally, sanctioned, hostage to its own macroeconomic mistakes, with severely diminished oil profits and pressured by domestic interests—has had to accept the need to loosen the economy, negotiate with business leaders, and guarantee full respect for private property. The government has flexibilized currency exchange policy, engaged in dialogue with business associations, spoken about facilitating foreign investment, permitted transactions in dollars, and hinted at possible privatizations of public companies.

For its part, the Democratic Unity Roundtable’s (MUD) return to the ballot box was a de facto recognition of reality: there are no shortcuts, military uprisings, invasions, shadow governments, or mass protests that can immediately remove the government from power. Despite such uneven circumstances, major disadvantages, and all kinds of abuses, elections are the opposition’s only path forward.

The campaign also heralded an interesting shift in the narrative across the political spectrum. In past elections, Chavismo has led reinforcement campaigns, with messaging addressed mostly to its hard base and especially emphasizing unity: “we’re all together” or “together we can achieve more.” This narrative was tied to messages of “anti-imperialist resistance” and staying “loyal” through difficult times. However, this time they pivoted to the slogan “Venezuela tiene con que,” an attempt at more optimistic messaging that seeks to appreciate what Venezuela has, encourage connection with the country’s brand, and persuade social sectors traditionally not linked with Chavismo.

In this sense, it would seem that PSUV candidates like Rafael Lacava in Carabobo, Jose Alejandro Terán in Vargas, or Georgette Topalían in Baruta, Miranda are the candidates that are best reading the changes happening in the country from within Chavismo. They ran convincing campaigns in alliance with business and commercial sectors and in consensus and dialogue with social actors unsympathetic to Chavismo. Lacava received the most votes of any Chavista candidate; Terán won support similar to that of his predecessor Jorge García Carneiro, a regional Chavista leader who recently died and had been undefeated in the state for 10 years; and Topalían achieved considerable votes in a municipality historically very adverse to Chavismo.

That said, the results in terms of voter participation remind Chavismo what the rest of Venezuela already knows: each day, exhaustion increasingly sets in as their base diminishes. The ruling party can govern as a minority one more time, but the electoral trend is a threat to the status quo. As such, Chavismo has to consider a broader overhaul of its politics.

Chavismo lost Cojedes and was close to losing the entire Llanos region that traditionally has voted for Chavismo. It lost municipalities like El Vigía in Mérida, as well as Zaraza and Guárico, and it even lost the mayoral seat in La Grita in Táchira, places where before it had totally dominated. It also lost the governorship in Zulia, one of the country’s most important electoral regions in terms of the number of voters.

Considering total votes, Chavismo was a minority in the face of the different united opposition forces. However, the opposition carried out a very traditional campaign, basically seeking to capitalize on discontent. The MUD did not have a clear message around key questions: Why vote now when before it wasn’t necessary? What would the opposition do if the government seized any gubernatorial or mayoral seats they ended up winning? Why bother winning governorships and municipalities? These unanswered questions led to internal divisions, fractures, and the decision by some sectors to abstain.

For its part, the Alianza Democrática, an alternative opposition force, based its campaign around regional leaders, like Henri Falcón, former governor of Lara. However, accusations of a “co-opted opposition” or “complacent opposition” due to its alliance with certain parties weighed heavily, and the coalition’s messaging hasn’t managed to dismantle this perception.

Finally, in these elections there was an enormous number of “third forces” or so-called “independents” with quite positive results, like Antonio Ecarri in Libertador and other very interesting candidates. These candidates represented new narratives of reducing polarization and rejecting the government but also the traditional opposition figures. They used language with a more liberal tone and put forward proposals that suggested a closer relationship with the people. Even in losing, these candidates won, because they left a small opening by managing to burst onto the electoral scene.

Within the opposition, there were leaders like Roberto Patiño, who failed to secure the nomination to run for mayor in Caracas, Andrés “Chola” Schloeter, a mayoral candidate in Sucre, and other young opposition figures, many of whom studied at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello and whose resumés include both NGO and political party training and community work in popular sectors. The presence of these figures seem to be symptoms, albeit in their early development, of changes within the opposition. However, opposition gubernatorial candidates who won their seats were regional leaders like Manuel Rosales, Morel Rodríguez, and Alberto Galíndez—long-standing figures from traditional political parties, whose political trajectories follow party lines and whose discourses are regionalist.

Division and the lack of a clear and unified message impacted the opposition. But the message that Venezuelan society is sending to the entire political class, including Chavismo, is that of abstention. Abstention is due to many things—migration, militant boycotts by the most radical opposition sectors, abstention for religious reasons—but in general it signals apathy.

It is important to consider that within Venezuela, there are many Venezuelas, and this could be said of any country. However, in our case, the economic crisis, the services crisis, and the transportation problems make the gaps between these realities much larger than we could have imagined.

At the peak of the economic crisis, the country awaited a political solution that would change everything. Chavistas waited for the government to take action, opposition supporters waited for a way to remove the government from power. All expectations rested in politics.

Today, this has changed. I feel that one Venezuela lives within urban, commercial, and service bubbles benefiting different socioeconomic classes that, thanks to de facto dollarization and entrepreneurial ventures, have found personal solutions to weather the situation. Those in this Venezuela are starting to show great apathy towards politics. They have found more efficient ways to resolve their problems. They take refuge within their private and family lives, aiming to take advantage of and benefit from opportunities.

There’s another Venezuela where the internet very rarely reaches, where the only TV signal is the government’s channel, where for eight hours a day there’s no electricity, and where no government program nor opposition leader has visited for a long time, except when they seek votes. Those in this Venezuela, forgotten by politicians, have also somewhat forgotten about politics. They are subsumed in their own daily survival and no longer want to be swindled by grandiose plans, unattainable proposals, and boring speeches.

Our political class must transform itself. It will do so slowly, but it will do so. The people will not return to politics if politicians do not emerge from the everyday life of the people. The only way to change the trend is to change the way we do politics. These elections were a symptom of the changes.

Damian Alifa is a Venezuelan sociologist.