Unlike the U.S. youth and countercultural movement of the late 1960s that famously intoned “don’t trust anyone over 30,” the leaders of the Chilean 2006 high school and 2011 university student movements have intentionally taken their political visions to the highest seats of government. Representing that generation, 35-year-old Gabriel Boric of the Convergencia Social party and the Apruebo Dignidad coalition won the presidential runoff on December 19, becoming Chile’s youngest president-elect. Despite right-wing critiques about his youthful inexperience and his disdain for wearing ties, Boric’s mass appeal is grounded in what he represents for the social movements that, since 2019, have redirected Chile towards a future without neoliberalism.

Boric defeated the right-wing Republican Party candidate José Antonio Kast with 55.87 percent of the votes—a narrow victory considering Kast’s personal links with the 1973-1990 military dictatorship and familial connections with the German Nazi Party through his father. While low voter turnout and apathy has handed previous presidential elections to the Right, in this election feminists, sexual dissidents (queers), and Indigenous organizations mobilized to campaign for Boric. As Javiera Manzi, a spokesperson for the 8 March Feminist Coordinator (8M), pointed out in an interview with Democracy Now!, unlike Brazilian feminists’ “Ele Não” (“Not him”) campaign against the 2018 far-right presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro, 8M decided to endorse Boric, underscoring the political stakes for maintaining and advancing feminist victories. Similarly, looming over the vote was the ongoing Constitutional Convention, and many Chileans understood that Boric’s win would secure the path to finalize the vote for a new constitution in September 2022.

Despite a notable lack of transportation that slowed people’s ability to reach their polling stations, Boric’s victory was declared early on election night. And although there was concern that Kast would take a page from the Trump handbook by claiming voter fraud, he conceded via Twitter and congratulated Boric for his victory. Outgoing President Sebastian Piñera was quick to invite Boric the following day to La Moneda, the emblematic presidential palace where socialist President Salvador Allende made his last stand during the September 11, 1973 coup. All parties emphasized democratic stability and continuity.

After walking through the halls of La Moneda, Boric reflected upon seeing Allende’s bust, stating, “We will continue to build upon Allende’s dreams.” His quote encapsulated the broader meaning of his victory as well as the outpouring of joy in the streets: his win signaled the resumption of that socialist dream brutally snatched from the Chilean people almost 50 years ago.

Boric, however, is not Allende, but a progressive seeking to negotiate reforms. Positive public comments about Boric by Richard Von Appen, the president of Society for Industrial Development (SOFOFA), demonstrates this difference. Von Appen has described Boric as someone with “a genuine interest to improve Chile.” Following Allende’s victory, however, then SOFOFA president Orlando Saenz took an active role in destabilizing the economy and later assumed an administrative role in the dictatorial government. While Boric’s triumph gestures towards upcoming social reforms, national and international capital interests understand that he does not intend to abolish capitalism. And some of these interests see his proposed reforms as necessary to stabilize the country after years of social unrest.

A Society Divided

The presidential runoff was unprecedented in prompting the largest voter turnout since compulsory voting ended in 2012. The youth vote played a valuable role, further putting into question the age-old commentary that the youth are disinterested in politics. This time, they proved interested in a candidate who spoke to their values and issues. Similarly, women were key as the largest voting group, and women under 50 voted overwhelmingly for Boric. Prior to the 1973 military coup, the women’s vote was historically conservative-leaning. The voting gender gap noticeably closed during the 2005 election when the Socialist Party candidate Michelle Bachelet won her first bid for president. However, the decisive women’s vote in the 2021 election is largely due to the current feminist movement, which has radicalized the populace and concretized specific demands that did not go unnoticed by the Left and Right.

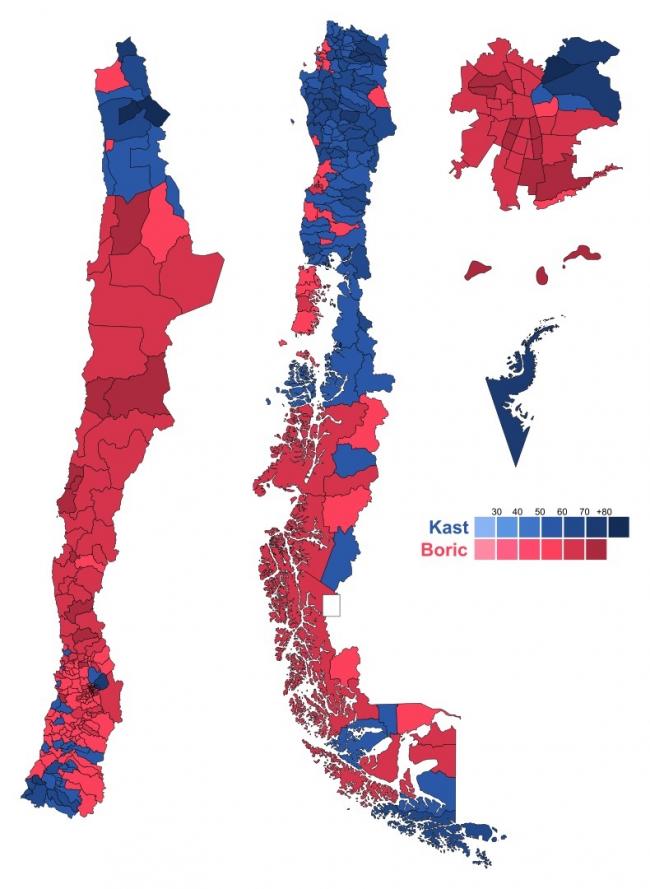

Notwithstanding the significance of Boric’s win, the results underscore the divisions within Chile, especially considering Kast’s quick rise to political prominence as a frontrunner for the Right. Although Boric received over half of overall votes, he lost or tied in some provinces. For example, 60.14 percent voted for Kast in the Araucanía region, while in the regions of Arica and Los Lagos, Boric won by a narrow margin with 50.61 percent and 50.03 percent, respectively. Kast made inroads in provinces where his campaign issues, such as immigration and land conflict, are most felt. His anti-immigration position and call to dig moats in the northern border resonated in Arica province, while the ongoing Mapuche land conflict in Araucanía generated support among German and Swiss-descendant landowners. Meanwhile, in provinces that voted overwhelmingly for Boric, expectations are high, and the social movements representing those regions will place their demands for the new president front-and-center.

Navigating High Expectations

During his acceptance speech and first press conference, Boric reiterated his plans to include women, sexual dissidents, and social movements outside of the main political parties in his administration. He has also announced plans to meet with the New Social Pact electoral coalition, which includes the Socialist Party, to negotiate their inclusion. As Esteban Valenzuela from the Social Green Regionalist Federation (FRVS) explained, Boric agrees with the need to widen his party’s political circles, include diverse social actors, and seek out pacts to advance reforms. The popular communist mayor of Recoleta, Daniel Jadue, who Boric defeated in Apruebo Dignidad’s primary, has pointed out that the Chilean Communist Party is the largest party in the president-elect’s coalition, emphasizing its expectations to be tapped for important positions. While it is challenging to predict Boric’s plans leading up to his inauguration on March 11, 2022, his victory—and the election results generally—nevertheless highlights significant opportunities and complications for Chilean social movements in the coming year.

There are concerns from the Left that the Boric administration might transform into a Concertación 2.0, offering piecemeal reforms while securing the status quo. His plans to include social movement actors and institutional players in his government raises questions about whether he can remain a strong enough olive branch to hold these strange bedfellows together.

Probably more concerning for the Boric administration will be how to manage ongoing economic and pandemic-related challenges, since his supporters will expect to see a considerable improvement in their lives. Likely foreseeing this concern, less than a month before the runoff election, Boric announced Izkia Siches, a medical doctor and ex-president of the Chile’s Colegio Médico, as his campaign manager. Siches, whose appointment elevated a feminist voice into his political circle, quickly declared the need for a UK-style health ministry independent of the administration in power and underscored the need for a universal healthcare system that “doesn’t leave anyone behind.” Meanwhile, on the environmental front, the conflict over the Dominga iron-copper mine that threatens the local ecosystem will serve as a barometer for his stance on an industry at the core of Chile’s industrial development and export economy.

Other challenges to navigate will include the issues that popularized Kast: immigration and Indigenous land rights. It is likely that the provinces that voted largely for Kast will become right-wing strongholds and continue to mobilize against Boric. What is less clear is how Boric will respond to those ongoing divisions. In order to appease the southern conflict, the new government will need to support Mapuche demands to expropriate lands taken from them during the Chilean colonization process (1871-1920), even though German and Swiss landholders will likely react strongly if they are not generously compensated. In the north, a stronger immigration movement is needed to articulate specific proposals to shift public discourse in their favor, as they are currently reliant on the Constitutional Convention to improve draconian immigration laws.

The Boric administration is a positive win and a vote of confidence for the Constitutional Convention. He will be expected to set a precedent of how to interpret and use the new constitution to make much-anticipated changes to Chile’s private pension and health systems, as well as to introduce protections for natural resources and expand social and Indigenous rights. Boric has described his new administration as feminist, and the Chilean feminist movement will hold him to those promises.

The Boric government will mark a new generation’s entrance into state politics, which has sparked excitement among some and concern among others. Seventy-five-year old Socialist Party senator, Carlos Montes, noted that this generational shift is positive, but maintained that the Boric administration should include “individuals of other ages.”

Boric’s win also has kindled excitement among the international Left. In the leadup to the election, celebrities like Pedro Pascal and Tom Morello, as well as economist Joseph Stiglitz and former Chilean president and current UN High Commissioner of Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, urged Chileans to vote for Boric. His international appeal reflected a widespread understanding of what the victory would mean for Chile’s new constitutional process and for the Left in the region, especially in the 2022 presidential election in Brazil. Workers’ Party candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was quick to capitalize on Boric’s win, posting a picture of himself wearing a Boric campaign hat and underscoring in his tweet the regional implications. Lula, president of Brazil from 2003 to 2010, was one of many Pink Tide alumni to publicize their support.

Yet Boric comes from a generation that mobilized against Bachelet’s “neoliberalism with a human face” policies. Will he be able to construct a social welfare capitalist state without neoliberalism, as Siches signaled, and usher in a new leftist tide for Latin America? Maybe, maybe not. But one cannot ignore the role that Chilean social movements have played in securing both a new constitution and Boric’s victory, and Boric, too, is well aware of their presence and force.

Romina A. Green Rioja is currently Visiting Assistant Professor in Latin American History at Claremont McKenna College and will assume the position of Assistant Professor at Washington and Lee University the next academic year. She researches race formation in 19th century Chile and writes about contemporary feminist politics in the Southern Cone.