“’We have hundreds of kilometers of beaches that aren't developed, and it's a waste,’ said the then Honduran Tourism Secretary (IHT), Ana Abarca in 2001. ‘We want strong tourism. We are going after the sun and the beach.’"(1)

These hundreds of kilometers of beautiful turquoise water and white-sand beaches, however, are by no means abandoned. A large part of the Honduran Caribbean coast has been home to dozens of Garifuna communities for over 200 years.

The Garifuna, whose language has been proclaimed a masterpiece of the oral and intangible heritage of humanity by UNESCO, are the descendants of a fascinating history highlighted by an astonishing capacity for adaptation and continuous resistance.

In 1635, two Spanish slave ships navigating from a region in West Africa that we identify today as Nigeria shipwrecked near the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent. Those aboard who managed to survive drastically altered their future destiny as slaves in the West Indies. Roughly a couple of hundred survivors found freedom in the island of Saint Vincent and soon mixed in with the local indigenous group known as the Red Caribs. Such blend of cultures gave birth to the

Garinagu people, also known as Garifuna or Black Caribs.(2)

“The British invasion of Saint Vincent in 1796 prompted a forced migration of the Black Caribs: first to Jamaica and soon thereafter to the Island of Roatan, which today belongs to Honduras. Over 4,000 Black Caribs were deported, but only about half of them survived the displacement to Roatan.”(3)

“As Roatan is quite small and infertile, the Garifuna struggled to subsist. Hence, they asked Spanish authorities for permission to establish a few communities in the mainland. The Spanish allowed the Garifuna settlements in exchange for military service, and so, the Black Caribs began to spread throughout Central America.”(4)

Today, the Garifuna have well-established communities along the Caribbean Ocean on the Gulf of Honduras, southern Belize, the Guatemalan coast (around the port city of Livingston), the Island of Roatan, in addition to coastal cities in Honduras and Nicaragua.(5)

Without taking into consideration a few adaptations, the Garifuna continue to subsist as their ancestors did: through fishing, hunting, the cultivation of yucca, beans, banana, as well as gathering wild fruits such as coconuts and

jicaco (cocoplum). “Our culture is based upon establishing a harmony with our natural environment”, explains Teresa Reyes, a community leader in Triunfo de la Cruz village.

During their four centuries of existence, the Garifuna have managed to survive numerous perils that have seriously endangered their survival: slavery, military aggressions by several European nations, forced migrations and natural disasters, among others. Nevertheless, socio-political and economic interest of our globalized world of today seem to pose the greatest threat yet: “it is the Garifuna communities' two most salient attributes – the simple beauty of their territory, and the uniqueness of their vibrant culture – that pose a threat to their existence.”(6)

Garifuna culture has experienced wide exposure in recent years due to the commercial success of their music and dance known as

Punta. Pulsating fast-paced beats characterize the Punta, which stems from an African war dance called the

Yancunu. In addition, the local

Gifity liquor has also become quite popular to outsiders. The mostly homemade fermented liquor derives from a medicinal drink containing a variety of herbs from which chamomile, anise, clove, St. John’s wort (hypericum), and allspice are predominant.

The neoliberal model for development, in which the Honduran structures of power base themselves in, has identified the Caribbean Coast, and in particular Tela Bay, as the perfect place to develop a mega-tourist industry: Beautiful “wasted” beaches – as described by former IHT secretary Abarca – populated by relatively few people (already perceived as exotic, easily persuaded, and who can offer entertainment as well as cheap labor) make up the perfect wish list for those within the structures of power.

Staying true to a pattern that seems to repeat itself endlessly in the Americas when it comes to the development of a Mega-project, the opinions of the local residents has not even been considered. “’We don’t want the mega tourist industry here,’ says Miriam Miranda, executive committee member of OFRANEH (Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras), the most prominent organization representing the Garifuna people. ‘Why do these people come to take our resources? They are not welcome.’”(8)

“The utmost peril against the Garifuna people today is the loss of our land,” states Benita Diego as she washes her family’s laundry in the community of San Juan.

Such struggle for the control of Garifuna territories began over 15 years ago. “Starting in 1992, the Marbella tourist corporation and other foreign investors, in complicity with local authorities and military personnel, began usurping property rights within the Triunfo de la Cruz community. Facing the risk of losing communal land titles, local and national organizations came together to expose the corruption and managed so suspend the fraudulent operations.” Today, the Marbella project remains at a standstill.(9)

Alfredo Lopez, undisputable human rights activist and Triunfo de la Cruz community leader who led the anti-Marbella struggle, was the first to face a reprisal carried out by those in power. On April 27, 1997, Lopez was charged with drug trafficking and immediately jailed. His case against the State of Honduras was taken to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (No. 124/01, Case 12.387) and ultimately ruled in his favor. Alfredo Lopez was finally released 7 years later.

In recent years, Garifuna activists have been living under a state of siege receiving innumerable death threats, having homes burned down, and have had three community members assassinated. “We find ourselves in a what can only be conceived as a war-like situation” declares Lopez during an interview.(11)

Today, the usurpation of lands, and hence the struggle and resistance, has moved away from Triunfo de la Cruz across Tela Bay. Surrounded by the Caribbean Sea on the north, the Micos Lagoon on the south, the Jeannette Kawas National Park on the west, and the urban area of Tela City on the east, we find the Garifuna communities of Miami, Barra Vieja, Tornabe and San Juan (in such order from west to east).

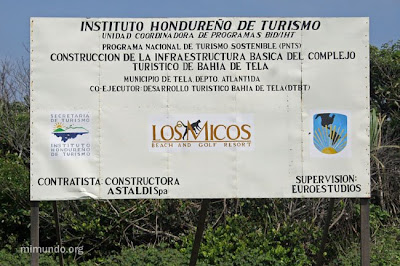

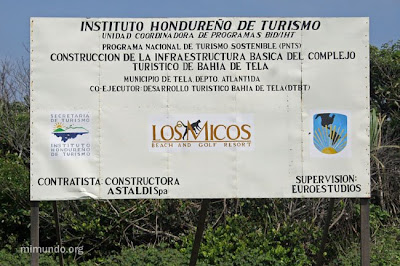

The Tela Bay Touristic Development Society (DTBT) hopes to set its new mega-tourism complex on top of these four communities. “Such mega-development, valued at US$ 161 million, seeks to promote Honduras’ image as a top-notch touristic destination… The first hotel should be finished in a year and a half, and, according to the schedule, the 18-hole golf course will be completed two months earlier. The Tela Bay complex will expand 3.2 kilometers along the beach and include four hotels of the five and four star category, 360 villas and a shopping center.”(12)

The deforestation process needed to begin construction of the 312-hectar Micos Beach & Golf Resort started on January 2008. According to government officials, the project will create “6 thousand direct and 18 thousand indirect jobs. It will also stimulate infrastructure and public service improvements for the neighboring communities.”(13)

Nevertheless, the local Garifuna populations are neither happy with the prospects nor the process so far. The DTBT has attempted to buy local land titles, which are held communally and not individually. Alfredo Lopez assures us that “in Miami and Tornabe the company has managed to buy off several local leaders.” Hence, the communal land has been divided up and sold to DTBT, creating serious intra-communal conflicts.

Carlos Castillo, local representative for OFRANEH and member of Tornabe community, stands in front of where once stood the hut in which he was born. A bulldozer recently destroyed his grandmother’s home.

The current construction work is carried out only a few meters away from Barra Vieja community, squeezed in between the troubled Miami and Tornabe communities. Barra Vieja is a historic settlement officially recognized by Tela Municipality since 1950. The 120 families that populate Barra Vieja have adamantly refused to sell. Hence, they represent the main obstacle to the DTBT investors as they all live along the most prized piece of real estate: the beach.

“Here we will resist until our death. Only in coffins will they manage to get us out of here!” declares Santos Antonio Garmendia, who has lived in Barra Vieja since the early 1950’s.

Over time, dozens of so-called “Indian” families (mixed European and indigenous ancestry) have incorporated themselves to the Garifuna communities, widely recognized for their predominantly Afro-Caribbean features. Modern Garifuna culture, however, is primarily identified by its lifestyle, cosmovision and use of language, rather than strictly from physical traits.

Besides the land problematic, strong resistance and criticism have risen due to the construction of a mega-project within the core area of a national park. “The project’s plan includes the filling of 87.5 hectares of the Micos Lagoon. Such changes will undoubtedly damage the wetlands and will bring incalculable ecologic consequences which are far more serious than any economic benefit which this project is supposed to generate.”(14)

“In addition, by drying out the body of water, neighboring communities are left unprotected to the rising number of tropical storms and hurricanes which develop in the Caribbean. The future looks bleak for the Garifuna populations of Miami, Barra Vieja, Tornabe and San Juan.”(15)

“International financial organizations are also playing a role in this conflict. The World Bank funds a land administration program known as the Program for the Administration of Lands in Honduras (PATH). Local organizations are afraid that this program is encouraging individual ownership of land at the expense of traditional communal land ownership practiced by groups such as the Garifuna. In the Tela Bay region in northern Honduras, this systemic problem is compounded by the Los Micos Beach & Golf Resort, a massive planned hotel complex funded in part by the Inter-American Development Bank.”(16)

Such strategy of dividing and buying has already worked in Miami. The communal land lot was divided in one square block per family, and most of the residents ended up selling out to the DTBT. Those who did not want to sell had were left with no choice as they found themselves surrounded by sold lots. “Look what has happened in Miami," states Alfredo Lopez. "The community hardly exists now. It’s a tragedy, they tricked the people into signing over their deeds, and now the community is destroyed. It serves as a warning for what will happen to the rest."(17)

“What will happen to my kids the day I’m no longer around? I will not sell out. I want them to have this land after me!” states a Barra Vieja resident.

“The Garifuna essence, our customs, traditions, and language are all directly tied to our lifestyle,” continues Alfredo Lopez. “Any brother who wants to share our cosmovision is welcome. But we do not want this touristic mega-project here.”

As an alternative, most members of the Garifuna communities are betting on the development of small-scale eco-tourism. Such industry provides direct income without any middlemen and is less stressful on the natural environment. The fishermen gladly offer to take tourists to Punta Sal or around the Micos Lagoon in their motorboats and canoes. In Miami and Barra Vieja one can find a few families willing to cook up fresh fish or the traditional rice and beans dish, while very rustic cabins can also be found to sleep in. Along the beaches, locals have built palm canopies: “We built them for the tourists as sun shelters. We want them to come visit us,” explains a Barra Vieja resident.

Trying to compete against the unlimited economic resources of the DTBT may seem an impossible task. Nevertheless, a women’s project in San Juan has taken up the challenge and found the courage to invest in its community. Three beautiful all-equipped cabins were inaugurated in April of this year. Each costs US$ 40 per night, regardless of how many guests stay, and each includes: full kitchen (stove, refrigerator, dishes and utensils), living-dining room (with TV), two bedrooms (three full-size beds overall), one bathroom and a veranda with two hammocks.

The cabins are located right next to the landmark “El Pescador” restaurant in San Juan, a slightly more urban setting than Miami or Barra Vieja and only 10 minutes from downtown Tela. For more information and/or to make a reservation please call: Benita Diego at (504) 3271-4652 or Esmeralda Arzú at (504) 3378-2723.

“We want a project that belongs to us. We don’t want outsiders to come and exploit us or remove us from our ancestral lands. We want to develop an eco-tourism industry which is ours and which will sustain our Garifuna cosmovision and respect the natural environment.” (18)

For more information and to get involved:

OFRANEH:

ofraneh@yahoo.com

Rights Action:

info@rightsaction.org

Versión en español aquí.

James Rodríguez is a Guatemala-based photographer and journalist. His work can be viewed online at Mimundo.org and his frequently updated blog, which originally published this photo essay.

Notes:

1 Ryan, Ramor. “The Last Rebels of the Caribbean: The Garifuna Fighting for their Lives in Honduras”. March 27, 2008.

http://upsidedownworld.org/main/content/view/1195/46/

2 http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garifuna_%28etnia%29

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Op. Cit. Ryan.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Informe No. 124/01, Caso 12.387

Alfredo López Alvarez. Honduras, December 3, 2001.

http://www.cidh.org/annualrep/2001sp/Honduras12387.htm

10 Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Caso López Álvarez vs. Honduras. Sentencia de 1 de febrero de 2006 (Fondo, Reparaciones y Costas).

http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_141_esp.pdf

11 Human Rights First. “Garifuna Activists Under Attack in Honduras”. November 23, 2005.

http://www.humanrightsfirst.org/defenders/alert112305_garifuna.htm

12 elPeriodico. Guatemala, January 14, 2008.

http://www.elperiodico.com.gt/es/20080114/economia/47473

13 Ibid.

14 Miranda, Miriam. “El BID y la Destrucción de la Laguna de Micos.” Comunicado de OFRANEH. La Ceiba, Honduras. June 3, 2006.

http://portal.rds.org.hn/listas/libertadexpresion/msg00505.html

15 Ibid.

16 Op. Cit. Human Rights First.

17 Op. Cit. Ryan.

18 Interview with Teresa Reyes. Triunfo de la Cruz Community, Tela, Atlántida, Honduras. July 18, 2008.