The gold nuggets are gone. Rarely do modern miners use picks to chisel away at metal deposits deep within the winding caverns of untapped mountain ranges. In the twenty-first century, much of our gold comes in the form of microscopic grains. Their extraction requires massive open pit mines where the world’s largest machines remove, reshape and reconfigure the surface of the earth in search of these tiny specs of precious metal.

As with bitumen extraction in the Canadian tar sands, modern gold mining operations dig up large swaths of dirt and mix it with fresh water and toxic chemicals to separate the precious metals from the soil. The wastewater is then dumped on-site in large retaining pools and contains high volumes of cyanide, mercury, lead, and arsenic, all of which are prone to leak and contaminate the local ground water supply. Open-pit gold mining is both resource intensive and energy intensive, and has only become viable in recent decades due to the rising market value of gold.

As gold prices have reached unprecedented heights, so have gold mining operations by targeting high-peak areas along the Andes mountain range where the earth’s bedrock juts upward, with its layers of sediment exposed to the sky. The region’s mountains and soils harbor one of the highest concentrations of precious metals in the world and, as a result, have attracted a myriad of international mining companies.

One of such companies is Denver-based Newmont Mining Corp., which opened its Yanacocha mine in the Cajamarca region of Peru in 1993. The company promised to bring improvements to the area by spurring economic development, but anti-mining sentiment grew quickly as residents watched the new mining jobs go to foreigners and Peruvians from other regions. At the same time, the area’s fresh drinking water became contaminated, causing an increasing number of people to be diagnosed with stomach cancer and other gastrointestinal diseases. There were also mass trout die-offs in Cajamarca’s rivers and, worse, farmers began to notice the teeth were falling from the mouths of their livestock.

More than 20 years later, Cajamarca remains the poorest province in Peru as Newmont tries to expand its mining operations with its proposal of the $4.8 billion Conga mine—essentially an enlargement of the Yanacocha mine. In response, Cajamarcans organized mass

movements against the new project, declaring they would no longer exchange resources for contaminated drinking water and few other benefits. In the fall of 2011, following a general strike that paralyzed the region, Peruvian President Ollanta Humala ordered Newmont to halt all work on the Conga site as the project underwent external review.

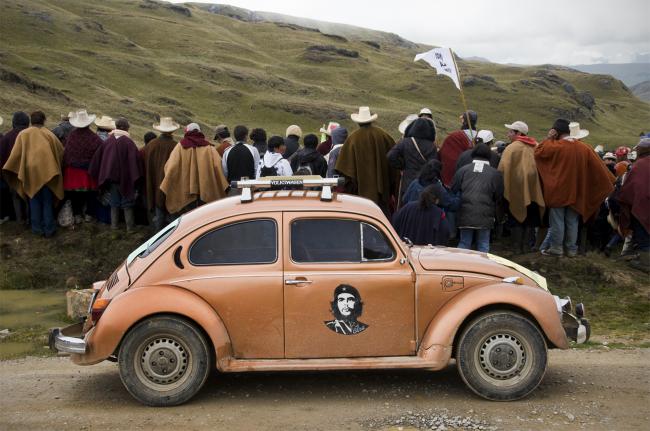

The Conga gold mine has been stalled ever since. Still, work crews have been spotted on the Conga site with construction equipment and Newmont executives have told investors they are simply waiting for a more favorable political climate before restarting the project. In the meantime, Cajamarcans have continued holding anti-mining demonstrations, sometimes on a weekly basis.

As protests continued in the spring of 2012, I visited Cajamarca to document events as they unfolded. During my time in the city, I stayed with José Luis, a 35-year-old who not only suffered severe stomach problems from ingesting contaminated water, but also lived in a house where tap water was shut off every night at 6 pm and sporadically throughout the day to meet the needs of the Yanacocha mine operating less than 50 km away. Like many Cajamarcans, the mine had adversely affected his life, but if Newmont offered him a job, he would take it out of the lack of alternatives.

In June 2014, the Peruvian government moved to gut the nation’s already dismal environmental policies in effort to boost investments from foreign mining companies and send a signal to growing anti-mining movements around the nation. The following images, stories, and quotes were gathered during my time in Peru between March and April of 2012. I present this work with people like José Luis on my mind, along with all Peruvians who have suffered needlessly at the hands of mining companies in their own backyards. It is through their lives that we pay the price of gold in the twenty-first century.

Diego Cupolo is an independent journalist, photographer, and author of Seven Syrians: War Accounts From Syrian Refugees (8th House Publishing). He serves as Latin America regional editor for Global South Development Magazine. See more of his work at www.diegocupolo.com.

Yanacocha mine.

Cajamarca through gold bar lenses. Foreign investors view Peru as a country covered in squares that represent mining concessions.

Anti-mining protest on March 16, 2012. The signs read, "More dignity. No to Conga!"

Security personnel in riot gear erected checkpoints to log the names of demonstrators and journalists during the World Water Day Rally, March 22, 2012.

World Water Day Rally, March 22, 2012, by Laguna Azul. The lake sits in the proposed mining area for the Conga project, and is part of the high-altitude headwater that supplies fresh drinking water in the region.

At its most basic level, the Conga mine would be an expansion of the Yanacocha mine pictured above. The mine estimates it will dry nearly five lakes to perform its operatives.

Cajamarcan children hold up signs (from left to right): "No more mines at the source of water springs"; "Water is a treasure that is worth more than gold: Yes to water! No to gold!"; "Today is a special day for everyone: We need to defend our lakes!"; "Children need water to live peacefully: Long Live World Water Day."

Cajamarcan residents share stories of resistance during World Water Day.

Police mounted on horses oversee a weekly street protest in Cajamarca on March 16, 2012.

Protesters gather and eat after a long day of action.