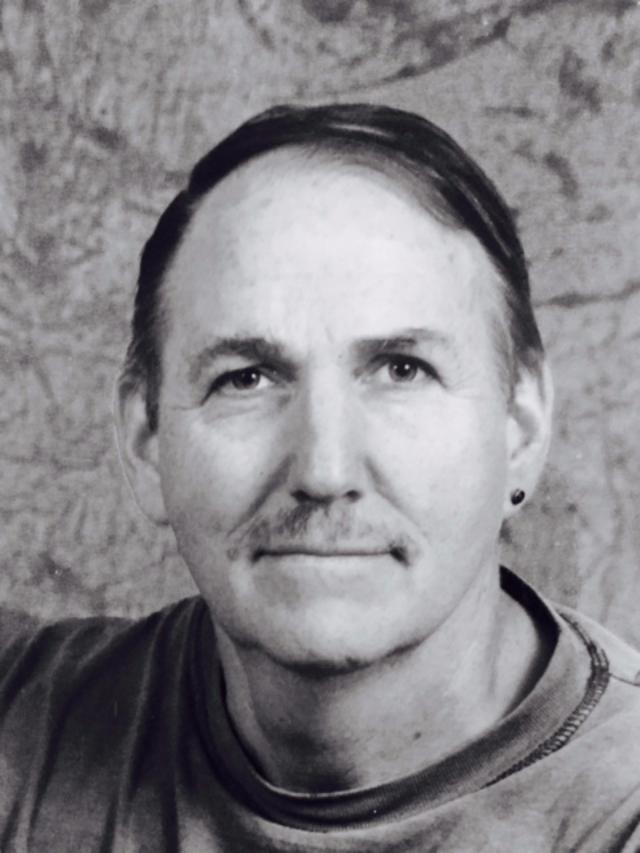

Roger Burbach, a NACLA staffer in the 1970s and 1980s, an Editorial Board member in the 1990s, and a prolific reporter and researcher for nearly a half century, passed away on Wednesday, March 5, at the age of 70. He died after a long and debilitating struggle with a variety of illnesses.

A paraplegic since suffering a spinal cord injury in Nicaragua in 1989, Roger never let his disability or subsequent illnesses get in the way of his writing and reporting. He faced his disability in the same way he faced the challenges of doing hands-on research and reporting from Latin America: with determination, honesty and a great deal of courage. His physical determination was a reflection of his professional and political determination to honestly analyze and report on the struggles for sovereignty and social justice in the Americas — and on the contradictions that some of those struggles fell into.

There was an unflinching honesty to Roger’s work. He never saw his commitment to solidarity and social justice as a commitment to sweep the contradictions of Latin American socialism under the rug. Nor, on the other hand, did he ever abandon his long-term commitment to the creation of a better world — one organized around the principles of fairness and solidarity.

The unflinching honesty of his work was mirrored by his unflinching acceptance of his disability; as a reporter, there was never an event he shied away from covering, or an interview he didn’t try his best to get despite his physical limitations. Nor did he shy away from asking for help when he needed it. When, back in the early days of Chavismo, he and I were reporting from Caracas and staying in the same two-star hotel, I never ceased to marvel at the way he routinely got hotel staff to carry him and his wheelchair up and down a long flight of stairs at least three or four times a day, or the way he got cab drivers to load his power-driven wheelchair into their trunks — sometimes with help from passers-by.

And just as he made no effort to hide any part of his disability, he made no effort to hide his doubts about revolutionary processes he otherwise supported — in countries like Nicaragua, Ecuador and Venezuela — while keeping his faith in the ultimate goals of those processes very much alive.

He was a firm believer in socialism but was scrupulously honest in detailing the shortcomings of actual socialist experiments both in and out of power. This critical loyalty to his socialist vision was probably best expressed in an essay he wrote for NACLA back in 1997 titled “Socialism is Dead, Long Live Socialism.” In it, he made ample use of the term “postmodern socialism,” as a tool with which to differentiate his humanist vision (grassroots democracy) from the actual historical reality (vertical models of socialism that were, in his view, failing throughout the world). Because of the many meanings and associations of the term “postmodern,” his use of it here never really caught on, but the vision of a horizontal movement toward socialism has been strongly influenced by Roger’s work.

“My general thesis,” he wrote in that 1997 essay, “is that twentieth century socialism has been defeated for two contradictory reasons. In those socialist experiments that were the most democratic, like Chile from 1970 to 1973, the United States was able to exploit relatively open political and economic processes to destroy them from within. On the other hand, in those centralized and verticalist socialist projects such as Cuba, the lack of authentic democratic processes weakened their popular support and led to the implementation of inefficient state-dominated economies.”

“Radical movements for change,” he wrote, “can only be successful to the extent that they are able to demonstrate that they are more democratic in their struggles and goals than the neoliberal democratic paradigm. In particular, they need to continually demonstrate that capitalist democracy is insufficient; that true democracy extends to the economic arena; and that the unregulated market advocated by neoliberals is incompatible with authentic democracy.”

In making this argument, he was able to honestly keep two conflicting commitments in his head at the same time: the Revolution’s need to defend itself and the Revolution’s commitment to liberty, equality and solidarity. “It was this paradoxical choice,” he wrote, “between maintaining the Popular Unity's commitment to democratic institutions and procedures and the need to take military steps to destroy the opposition that makes Chile the most tragic socialist experience in the Americas and perhaps in the history of twentieth century socialism.”

After the 1994 Zapatista Rebellion in Mexico, he co-authored Globalization and Its Discontents: The Rise of Postmodern Socialisms with Orlando Nuñez and Boris Kagarlitsky. Inspired by — and writing about — the Zapatistas, he was able to imagine the construction of a society based on respect and equality for all.

Roger was a Peace Corps volunteer in the Peruvian Andes from 1966 to 1968. From 1971 to 1973, while conducting research for his Indiana University doctoral dissertation in Chile, he worked with dependency theorists Andre Gunder Frank and Theotonio Dos Santos at the Center for Socio Economic Studies in Santiago. He paid a brief visit to Berkeley in 1972 and then returned to Chile later that year, remaining through the coup.

With the overthrow of President Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973 and the death of his friends Frank Teruggi and Charlie Horman at the hands of the Pinochet dictatorship, he became a dedicated campaigner for human rights and social transformation. After the military coup he left Chile, made his way back to the United States, and came to work for NACLA in what was then our West Coast office, contributing extensive research to NACLA reports on Chile in the 1970's. Together with Patricia Flynn, he also did important research on the global role of U.S. agribusiness during that period, publishing, together with Flynn, Agribusiness in the Americas in 1980.

At the time of his death Roger was working on a political autobiography in which he emphasized his life-long commitment to Chile. He returned from Chile determined to become a more effective anti-intervention activist. And that, he once told me, is how he got involved in Nicaragua. “It was actually because of Chile. When the Nicaraguan Revolution happened, I knew the United States was going to screw it over as much as it could. I did it out of anti-imperialist solidarity. I went to Nicaragua and started working with NACLA people on the unfolding Nicaragua story.”

He was an enthusiastic supporter of the 1979 Sandinista Revolution, and spent the next decade traveling extensively to Nicaragua and El Salvador to write about the popular resistance to the interventionist polices of the Reagan and Bush I administrations. He worked with the Sandinista Front’s Directorate of International Relations on a project established to analyze U.S. foreign policy. Roger received the Carlos Fonseca Award from the FSLN in 1986 for co-authoring with Orlando Nuñez, Fire in the Americas: Forging a Revolutionary Agenda. He conceived of his research and reporting as weapons to advance the cause of liberty and justice for all. He was optimistic to the very end. He was a demanding and generous compañero. He will be missed.

A memorial service will be held in Berkeley on Sunday March 15 at 2:30 PM at the Berkeley City Club, 2315 Durant Ave.