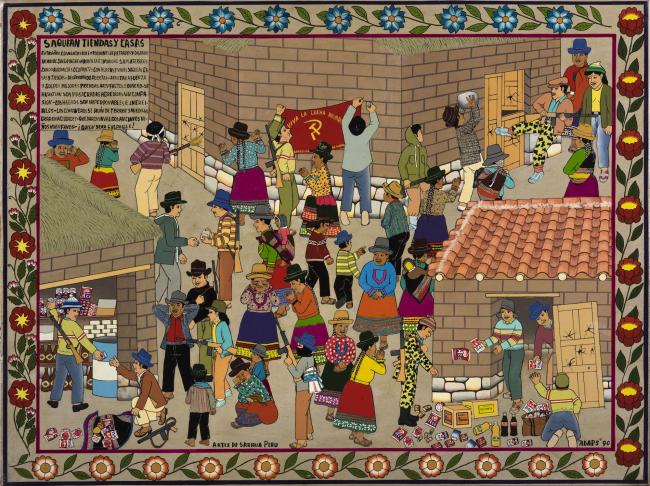

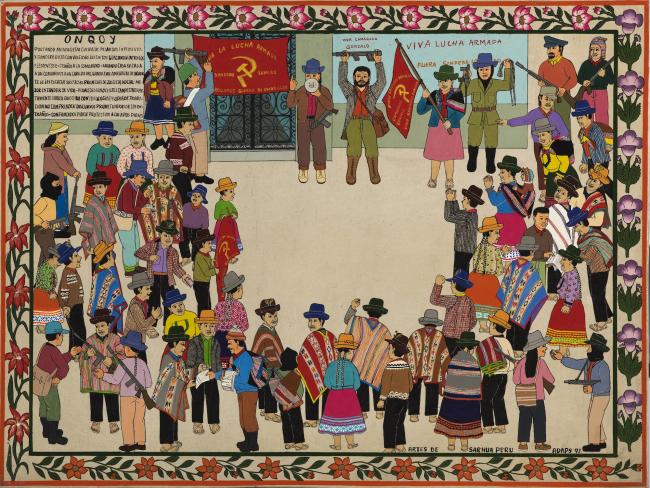

Insurgents looting stores and houses in an Andean community (Fig. 3). A group of “guerrilleros” with machine guns giving instructions to peasants gathered at a public plaza alongside a group of masked armed individuals. The peasants hold up raised left fists. One peasant woman waves a red flag with a sickle and hammer. In the background, there is a red cloth with symbols of the Shining Path (Fig. 2).

The described paintings are part of a collection of artwork depicting atrocities committed against Indigenous Quechua-speaking people during Peru’s internal armed conflict from 1980 to 2000, which the Detroit-based non-profit organization, CON/VIDA Popular Arts of the Americas donated to the Museum of Art of Lima (MALI) in 2017. The collection includes 31 paintings created by the Asociación de Artistas Populares de Sarhua (ADAPS)—a nonprofit founded by artists who migrated to Lima from the peasant community of Sarhua in Ayacucho, the epicenter of Peru’s armed conflict, two textiles made by Edwin Sulca, and one retablo altar piece by Nicario Jiménez. These artworks document the crimes against humanity committed by both the armed forces and the Shining Path during Peru’s internal armed conflict, such as murder, rape and sexual violence, torture, and enforced disappearances.

According to the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the Shining Path was responsible for 54% of the estimated 69,280 dead and disappeared during the conflict, while the armed forces were linked to 34% of deaths and disappearances. Compared to other insurgency groups in Latin America, the Shining Path stands out for its high degree of culpability in human rights violations.

The exhibition never made it to the Peruvian public. When the collection arrived to Peru in 2017, the government promptly confiscated it and placed it under investigation for its alleged “apología del terrorismo,” (defense of terrorism) by the Counter-Terrorism Directorate (DIRCOTE) and the Public Prosecutor’s Office. Defense of terrorism became a crime under Law 25475 in 1992, part of a package of special anti-terrorist legislation that was later declared unconstitutional after the fall of former president Alberto Fujimori (1990-2000). The law was further modified, most recently in July 2017, when Art. 316-A was incorporated into Peru’s Criminal Code. This latest version to the law was a response to a Labor Day march where demonstrators of the political wing of the Shining Path known as the Movimiento por la Amnistía y Derechos Fundamentales (MOVADEF) carried signs that featured photographs of imprisoned Shining Path militants and their leader Abimael Guzmán. The amendment mandates prison sentences of eight to 15 years for the use of books, texts, visual images, or recordings that exalt, justify, or glorify terrorism.

The new amendment set the stage for the government’s confiscation of the artwork, which it held from October 2017 until January 15, 2018. In May 2018, the District Attorney’s Office determined there was insufficient evidence to file charges for “apología del terrorismo,” but the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Antiterrorism has since appealed the decision.

On January 25, Diario Correo, a Peruvian daily tabloid, broke the news about the Public Prosecutor’s Office seizure of the collection in order to conduct a preliminary investigation to determine if the paintings defended terrorism. The government has not made public which aspects of the artworks they find suspect, but the conservative media and some politicians have argued that the paintings’ portrayal of peasant militancy, such as their raised fists and masked faces, and the proliferation of Shining Path symbols appear to defend terrorism.

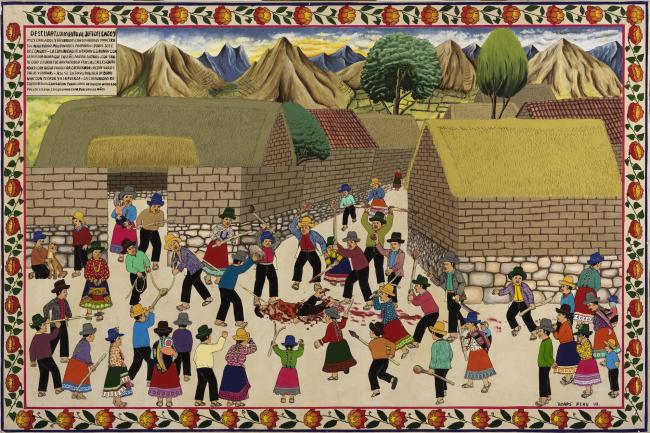

However, the paintings’ content refutes this interpretation in a number of important ways. In 12 of 15 of the paintings that mention the group direcctly, the artists refer to the Shining Path as onqoy, which in Quechua means “sickness”—the Sarhua artists perceived the Shining Path as a “plague” and a threat to their community. Only two paintings in the series contain the words “guerrilla” and “subversives,” and in both cases the artists denounce their destructive actions. One of the last paintings in the series, titled Descuartizamiento del Jefe del Onqoy (Fig. 4), depicts the community killing the Shining Path leader of Sarhua.

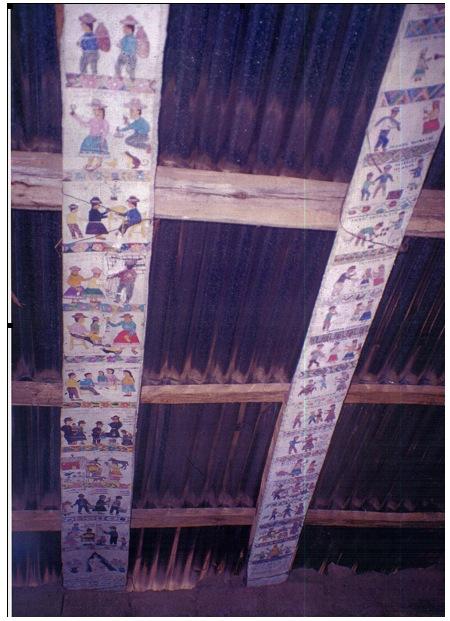

Of the 31 paintings, 24 come from the series Piraq Causa (Who is to blame?). These paintings from the ‘90s depict what residents in Sarhua call los tiempos del peligro (times of danger), which ravaged the community in the 1980s. The artistic style derives from Sarhua’s traditional tablas pintadas (painted boards), which depict family genealogies and are traditionally given as gifts to new homeowners by their compadres (children’s godparents). These traditional tablas are also called alza-techos (roof-lifters), because they are used as roof-beams to offer symbolic support to a house (See Fig. 1).

Yet in Piraq Causa, the artists produce the modern tablas on planks of wood that can be displayed on walls for public view. Rather than family genealogies, the planks depict myths, customs, and old traditions but also events that threaten livelihoods. The Piraq Causa paintings denounce the destructive presence of both the Shining Path and Peru’s counter-insurgency police and military throughout the conflict.

Any argument suggesting that the Piraq Causa series defends terrorism remains entirely unclear and unsubstantiated. The work was a visual response to the life in Peruvian Andes under the Shining Path, and thus involved meticulously representing the means they used to impose their ideology and rule. Why should the use of the word “guerrilla” in a superficial and decontextualized analysis count as evidence of defense of terrorism? Why should the detailed representation of Shining Path symbols and political propaganda be taken as proof of sympathy and support for them?

When the paintings were first created in the 1990s, the artists shipped them from Peru to Costa Rica, where the owner of Piraq Causa lived, in order to shield themselves from being targeted by either Shining Path or the government. The return of the art to Peru followed the country’s transitional justice process, which began in 2000 after Alberto Fujimori’s resignation as president when he became implicated in massive fraud and grave violations of human rights. Five years after the government released its Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report in 2003, the government accepted funding from Germany to build the Lugar de la Memoria, Tolerancia e Inclusión Social (LUM), a museum that would commemorate the victims and educate citizens on the root causes of the conflict. The following year former president Fujimori was convicted to 25 years in prison for crimes against humanity.

CON/VIDA’s efforts to return the artworks to Peru were part of the nationwide effort to recover historical memory. In past years, the collection toured the Americas with eight major exhibits in the United States and one in Costa Rica. Thus, CON/VIDA began to seek out a Peruvian institution that was interested in the collection and had the capacity to properly attend to the artworks, eventually settling on the MALI.

Government Atrocities

The nature of the terrorism allegations and censorship reveal much about the state of human rights in Peru today. The paintings that allegedly defend terrorism relate to only the Shining Path, even though Piraq Causa also includes nine paintings that identify the counterinsurgency police and military as responsible for human rights abuses. To implicate these paintings would mean framing the government as perpetrators of violence—something the government might be conveniently skirting.

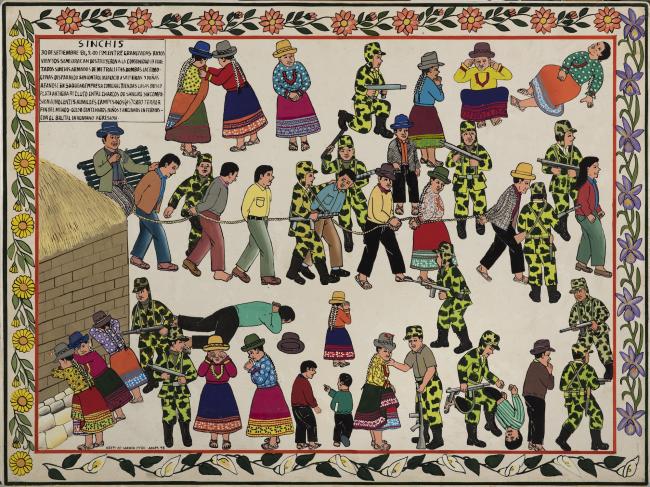

For example, Sinchis (Fig. 5), the second painting of Piraq Causa series, depicts abuses perpetrated by the Sinchis, or counterinsurgency police, when they arrived to Sarhua on September 30, 1981 to apprehend villagers accused of alleged terrorism. An investigation carried out by the Human Rights Subcommission of Parliament in October 1981 found the Sinchis had abused their authority and responded arbitrarily to accusations of terrorism. This event “created doomsday terror,” as the text on the painting notes, and led to the onset of political violence in Sarhua.

The Shining Path would appear in Sarhua soon after the Sinchis’ incursion, capitalizing on the population’s traumatic experience with the counterinsurgency police to garner support and declare Sarhua a liberated zone under their control. In August 1984, Sarhua became the site of a military-perpetrated massacre of approximately 25 alleged terrorists from the neighboring peasant communities of Huamanquiquia, Uchu, and Tinca, detailed in Infierno en Quechawa (Fig. 6), which states that “numerous innocent peasant men and women mostly adolescents suffered [and were] coerced to join the guerrilla ranks under death threat” and were “burned alive” while locals witnessed “hundreds of human beings being charred.” The painting does not detail how the military also forced the peasants of Qechawa, an outlying annex of Sarhua, to dig mass graves to conceal evidence of the crime.

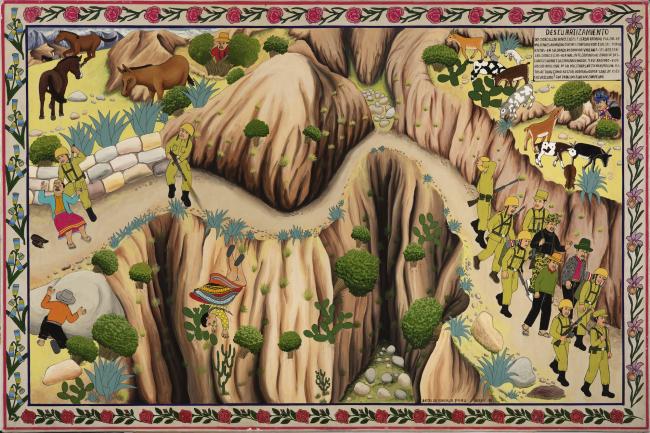

In Descuartizamiento (Fig. 7), the artists recount the rape and torture of two young peasant women, one from Huamanquiquia and the other from Uchu. “Two young maidens were rounded up by 39 armed military men who mistook them for terrorists—in their long journey they rape the defenseless maidens—at the end of the isolated trail one was dismembered and the other shot as she jumped off a cliff,” the caption reads. “The military’s irrational behavior deserves no forgiveness—they behave like human beasts nobody knows of this savagery—what a lethal fate to be a peasant woman!” The human rights violations depicted in the Piraq Causa series are not limited to Sarhua, but representative of what happened across Andean communities during this era.

As demonstrated in many of these paintings, the military justified their behavior by deeming their victims terrorists. Today, more than 30 years later, Quechua-speaking people like the artists from Sarhua continue to be targeted by allegations of terrorism—in this case for sharing how their community suffered during times of extreme violence. The current lack of discussion about human rights in the censorship of these artworks suggests the government could be enforcing “defense of terrorism” laws as a way to deny reckoning with the atrocities perpetrated by the armed forces during the internal armed conflict.

Censorship Unabated

Not everyone in the government has agreed with the censorship of the paintings. Alejandro Neyra, Peru’s Minister of Culture, rejected the allegations that the works defend terrorism and proposed “better parameters to determine what is art, and how to tell it apart from terrorist propaganda.” On February 10, during the inauguration of Carnival in Ayacucho, Neyra announced that the paintings of Sarhua at large should be declared cultural patrimony of Peru.

Although Neyra resigned along with President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in March of this year, the recently appointed Minister of Culture, Patricia Balbuena, has respected the former Minister’s initiative. Yet this deserved recognition of the artists of Sarhua does not eliminate the threat against freedom of expression outlined in these laws. In fact, aiming to distinguish between art and terrorist propaganda might only lead to harsher forms of censorship and the de-politicization of art more widely.

As of August 2018, there have been no further changes to the law, the case of the paintings of Sarhua is still waiting for the appeal resolution of the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Antiterrorism, and more attacks against artworks and cultural institutions documenting the internal armed conflict have followed. In May, a screening of “La Casa Rosada,” a film about a notorious military torture center in Ayacucho of the 1980s, directed by the recently deceased Palito Ortega, was removed from numerous movie theaters after Congressman Edwin Donayre, a retired military officer, insinuated that the film denigrated the army and could be considered defense of terrorism.

In the same month, the LUM, inaugurated in 2015 to educate youth about the internal armed conflict and commemorate its victims, also became a target of Donayre’s attacks. Dressed in disguise, Donayre joined a guided visit of the museum and secretly recorded it to use as “proof” that the museum docent and the permanent exhibit defended terrorism.

Government censorship continued in June when pro-Fujimori Members of Congress requested the Ministry of Education review the content related to the “times of terrorism” in school textbooks. The Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos (CNDDHH) has pointed out that this is an attempt to censor information that implicates the military and politicians in serious war crimes. The defense of terrorism law supports the reactionary denialism that seeks to conceal the armed forces’ systematic violation of human rights in Peru and their impunity. The “times of danger” and the politics of fear are clearly far from over in postwar Peru.

Olga González is associate professor in the Anthropology Department and Director of the Latin American Studies Program at Macalester College. She is the author of Unveiling Secrets of War in the Peruvian Andes (University of Chicago Press, 2011). She has been the advisor for two traveling art exhibits in the United States, Weavings of War; Fabrics of Memory and Ayacucho: Tradition and Crisis in Peruvian Popular Art. She also curated the exhibit Ayacucho: The Times of Danger in 2012. Her current research focuses on memory and visuality in post-war Peru.

The artworks above were reprinted with permission from the Museo de Arte de Lima. Donación Asociación CON/VIDA Popular Arts of the Americas. Photography by Daniel Giannoni. Archi, Archivo Digital de Arte Peruano.