In the pitched battles over immigration, rhetorical binaries dominate. Republicans refer to migrants as aliens. Democrats trumpet innocent children traumatized by extremist Trump-era practices. Migrants are either good or they’re bad, and in the imaginations of politicians and pundits, it’s possible to put some people into one category and other people into the other.

Where talking points end, laws and policies begin. Under the illusion that people can easily be boxed, immigration law assigns privileges and sets policing priorities based on markers of undesirability. Born in the right Western European country and even Trump thinks you’re great. Drop enough money into a Vermont ski resort and a green card is likely to follow. But live in poverty and you lose favor with visa adjudicators. Develop a criminal record and you win the attention of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency’s SWAT-style law-enforcement agents.

Like the simplistic conversations of politicians, the this-end or that-end binary of immigration law and policy discussions presumes a stark distinction that doesn’t reflect human experience. People aren’t so easily categorized. Most of us aren’t pictures of purity. We make mistakes. We fail. We engage in mishaps and regrets. At times, remorse begins before the sin is complete. But the morality tale of immigration law makes no such allowance. Since the days when it seemed George W. Bush might be able to steer a massive immigration reform bill through Congress, pro-migrant rallies have often featured a simplified version of this claim to innocence: “We are not criminals,” banners frequently attest. On the opposite end of the simplistic binary, the virulently anti-migrant organization Federation for American Immigration Reform maintains a list of crimes committed by migrants, “demonstrat[ing] that better prevention of illegal immigration is a public safety issue.”

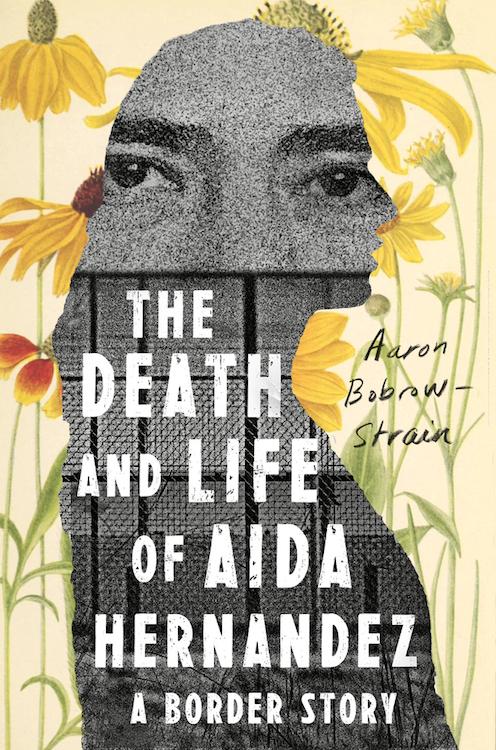

Though they differ substantially in motivation, embracing an overly simplistic view of migrants from the left or the right produces troubling consequences for immigration law and policy. When that happens, as it has repeatedly for decades, ordinary people suffer. In his deeply researched, captivating new book, The Death and Life of Aida Hernandez: A Border Story, Aaron Bobrow-Strain illustrates the complexity of human experience that sometimes accompanies migrants because, like the rest of us, they are people. The woman of Bobrow-Strain’s title, whose name has been changed, defies categorization. She is a domestic violence survivor who, on at least one occasion, lies her way into the United States. She is a doting mother who steals from the local Walmart. She is a Mexican citizen by birth, but in every other way she is the child of Douglas, Arizona. Born south of the border line, Aida Hernandez heads to Douglas when her parents split up and her mother takes the children to live near her boyfriend, a minor despot whose abuse becomes the first in a long line that Aida experiences directly.

But where the ordinariness of human experience ends, the consequences of immigration law often begin. Armed with a border-crossing card, her entry into the United States was legal, but, soon enough, her stay was not. As a child, the legality of immigration law was rightly beyond her capacity to understand, but even a child isn’t unaware of the basic pillars of life around her. Aida’s daily experience, Bobrow-Strain recounts, was cabined by the borderline to the south and interior immigration checkpoints to the north. Going south might mean not returning to the place she had come to call home, where her classmates gathered, and her child was born. To the north, Phoenix was as much a mirage as the blurry watering holes that litter the desert in the eyes of the parched wanderer.

In Douglas, Arizona, Aida’s life was pressured by the weight of poverty and the ever-present fear of a liminal place in the United States. She embodied the United States in every way except the only way that matters to immigration law. By the time she reached high school and married, Aida, still in Douglas, became the picture of immigration law’s power to marginalize. Her husband, a high school gem, soon cratered under the pressure of early parenting and marriage, resorting to the worst exercises of his privileged position as a male United States citizen. He punched walls and threatened deportation.

Like Aida, I was born and raised in a border community. In the Río Grande Valley of South Texas, people come and go across the international border line for good reasons, bad reasons, or no reason at all: to while away a Saturday afternoon, visit a doctor, shop at a bustling mall, or see family. For those of us with permission to cross, the borderline is a tiresome inconvenience. Standing in the hot sun on a June afternoon, I was reminded that it didn’t used to be this way. Back in the 1980s of my youth, by today’s standards, lines were short and vetting perfunctory.

The borderlands of the United States and Mexico are a place where citizenship, in all its forms, matters immensely. To be a U.S. citizen is to be able to access the magical U.S. passport that ferries people north and south. To be a U.S. citizen privileged with the income and entitlement of the professional class is to afford the passport fees that relegate the border into a sweaty inconvenience, but usually keep it from becoming anything more. I was reminded of this some time ago when I arrived in South Texas on a research trip. I knew I needed to cross the Río Grande, but as I reached for my passport at the Denver airport, where I live, I realized it was back at home. Too late to go home, I boarded the flight and headed to the border.

Later that day, I found myself feet away from the international boundary staring across a bridge into Mexico. “I need to cross,” I told a Customs and Border Protection agency officer who I flagged down before passing the turnstiles into the limbo area between the two countries’ immigration stations, “but I only have a scanned copy of my passport on my phone. I forgot the printed book back in Denver.” “That’s fine,” she said. “Do you have any other type of government ID?” When I pointed to my Colorado driver’s license, she explained, “Just show that to the officer and you won’t have a problem.” Sure enough. I didn’t.

U.S. citizenship is murky like this. I can’t drive from the Río Grande Valley to San Antonio without having Border Patrol officers ask me about my citizenship at interior immigration checkpoints, but, most of the time, my class privilege works in tandem with my formal claim to U.S. citizenship to allow me to traverse the borderlands remarkably smoothly.

Without those, life could become a frenzied whirlpool of despair in a moment. One week, Aida left Douglas for a night partying in Agua Prieta, Sonora, the town that hugs the border alongside Douglas. They spent the night at the kind of place where my high school friends used to head on Friday nights for cheap beer and loud music. Fitting into the masses of young, drunken Arizonans streaming northward after last call, she made it back without a problem. A week later, the edifice of belonging in the United States came tumbling onto her. After another alcohol-fueled evening dancing away with southern Arizonans and northern Sonorans, she made it to the port-of-entry, but not across. Suddenly, Agua Prieta wasn’t just a place with trendy nightclubs and easy beer. Now it was the place where she was trapped.

She was born there, but in the years it had taken to transform from a little girl to a woman with a young child of her own, Agua Prieta had become a foreign land. Stuck on the southern side of the boundary line while her son remained with his grandmother, Aida’s mother, to the north, the geographic distance between the two was meager—just a few miles—but politically it might as well have been worlds away. To Aida, the boundary line wasn’t imaginary. It was real: steel and concrete, law enforcement boots, and Border Patrol trucks.

Despair has a way of turning bad situations worse. Ignoring the advice that her sister and father gave her, Aida took a job as a waitress at a seedy border nightclub. This time she would end her first night’s work and barely escape with her life. “Your mom’s dead,” someone later told Aida’s son. She wasn’t, but it would take a while before she could prove it.

When she was back in Arizona, again with short-term permission, and well enough to return home, she promised her son that she wouldn’t leave him again. But without a clear hold on authorization to be inside the United States, that was always just a hope—a wish that a sixty-piece Lego set surreptitiously tucked into her purse at the local Walmart would collapse. It was a gift for her young son, but to immigration officials it was nothing more than the trigger that would send Aida into an ICE prison in Eloy, Arizona. Eventually, she would win a reprieve from an immigration judge, move to New York City, and, there, in the glitter of the most romanticized city in the United States, she would run directly into the obstacles of grinding poverty.

The Death and Life of Aida Hernandez is no fairy tale. It’s not an uplifting story of plucky migrants and isn’t the handbook for congressional immigration-law reform efforts. That is precisely why it is such a powerful testament to migrants that deserves a more central role in immigration law debates. Bobrow-Strain, a professor of politics at Whitman College, isn’t interested in an easy prescription to the muck of immigration-law reform conversations. On the contrary, his book, like his subject, is a complicated, contradictory story full of messy narratives, lousy options, and questionable choices.

Bobrow-Strain hasn’t written a story limited to current debates about immigration law and policy. Rather, like other great storytellers, he has written what is better described as a story about people who happen to be migrants. It’s the people who animate his account, and not the circumstances that convince us to care about the people. And in the people of Bobrow-Strain’s book, there is a lot to mine. “I died and came back to life,” Aida once told her mother.

There is a mystical quality to Bobrow-Strain’s story. Far from the borderlands, read through the prism of national debates about immigration law and policy, much of the book might come across as far-fetched. He claims to have written a book that “occupies a space between journalism and ethnography, with a dash of oral history and biography.” Like the borderlands, Bobrow-Strain has written a book intended to transcend the boundaries of multiple genres and disciplines.

And as is often the case, the borderlands story he tells might raise suspicion from a distance. In a New York Times review, the journalist Michelle Goldberg wrote that he “asks us to put an unusual amount of trust in him as an author.” Perhaps, but it’s not the reader who needs to be cared for. Bobrow-Strain’s greatest responsibility is to the people who shared their stories with him so that he could share them with us. It’s almost impossible to independently double-check those stories. He uses pseudonyms for almost everyone who appears in the book and breaks other standards, the prickliest of which being that he is sharing profits with and some amount of deference to his title character. It is to Bobrow-Strain’s credit that we know this because he tells us.

For all its standard-deviating, fantasy-creating features, Bobrow-Strain’s book is eminently believable as what its subtitle claims: a border story. In the borderlands, the extraordinary is ordinary. Families are comprised of U.S. citizens, migrants who have permission to be here, and others who don’t. Border Patrol agents live alongside immigration attorneys. Elementary school classes of refugee children meet on sidewalks. Grandmothers send tacos to migrants stranded on bridges. Sometimes, even the border itself moves, as it did in South Texas early in the 20th century when an irrigation company illegally cut a canal between two sections of the Rio Grande River, shifting an entire community in Texas south of the international waterway. In the borderlands, nothing is too much to be unheard of—not even coming back from death.

César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández is an associate professor of law at the University of Denver. His next book, Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants, will be released by The New Press in December 2019.