ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED MAY 30, 2019

At first glance, the apartments at Village Lumane Casimir do not look like the center of anything. They stand alone on the edge of a desolate floodplain, a dozen miles outside Port-au-Prince, Haiti. In 2011, the Haitian government paid a firm from the neighboring Dominican Republic $49 million to build 3,000 units to house survivors of a 2010 earthquake that had destroyed most of the capital city. Less than half of those apartments ever materialized. Many others remain half-finished, vandalized, or vacant.

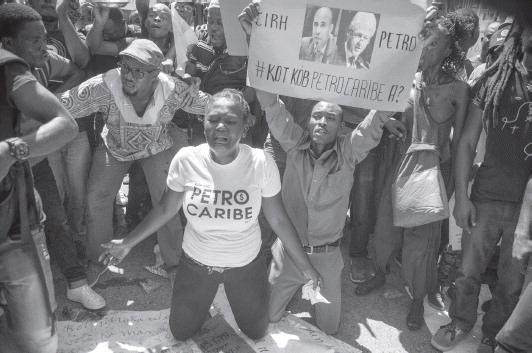

The apartment complex’s general air of abandonment belies its critical role in Haiti’s biggest scandal in recent years. Today, revelations of enormous-scale government corruption for public works projects like Village Lumane Casimir have sparked a protest movement that threatened to topple President Jovenel Moïse. The housing complex was built with funds the country saved through its participation in Venezuela’s Petrocaribe program, in which the Venezuelan government allowed the Haitian government to purchase oil on a deferred-payment plan, and to use the savings left to strengthen state-run programs. Yet the apartments’ sorry state has bolstered allegations among residents and neighbors that high-level officials, bureaucrats, and construction companies pocketed those funds for themselves.

There is reason to suspect this. In 2017, a Haitian senate commission published a report claiming that Moïse and others, including two prime ministers, misappropriated, wasted, and embezzled nearly $2 billion in Petrocaribe funds that had officially been earmarked for earthquake recovery initiatives. Village Lumane Casimir is but one example of hundreds of construction projects that the government paid for since the disaster, but were either never started, never finished, or offered an anemic version of what had been promised.

The report’s revelations provoked public outrage amid a larger economic crisis that has aggravated the precariousness of ordinary life in Haiti. Protests demanding transparency, accountability, and an end to inequality have shut down commerce and transportation and left nearly 40 people dead since August 2018 as of press time. Haiti is today struggling through a financial recession that has exacerbated already grinding nationwide poverty. The value of Haitian currency has plummeted in the midst of rampant food insecurity as domestic agricultural production continues to decline. And Haiti will theoretically have to pay back the Petrocaribe money at some point, which will no doubt require squeezing even more out of a long-suffering population.

The ties between corruption and construction are neither new nor specific to Haiti. Building large-scale structures involves huge sums of money, multiple stages, and highly complex transaction networks. This makes oversight difficult and opens ample opportunities for bribery, price inflation, and payment for incomplete or shoddy work. A 2017 literature review by Albert P.C. Chan and Emmanuel Kingsford Owusu in the Journal of Construction Engineering and Management identified bribery, fraud, and collusion as the main sources of corruption in construction, followed by embezzlement, nepotism, and extortion. Globally, 10 to 30 percent of the value of large construction projects are lost on average through corruption, according to the World Economic Forum. This corruption comes at a cost of “shorter lifespan of buildings, collapse of buildings, and the claiming of human lives,” wrote Chan and Kingsford Owusu.

As my research into the history of construction in Haiti has shown, however, corruption practices are neither natural nor inevitable. In fact, illicit income extraction is a constructed mode of governance that needs constant modification and upkeep to survive. Its institutions are weak. “State forms are constantly being created, reproduced, maintained and modified … these processes of reproduction and change are intertwined with the historical evolution of the particular society and culture within which the state functions,” wrote Michel-Rolph Trouillot in the 1990 book, Haiti: State Against Nation. Indeed, enormous effort has gone into adapting strategies of kleptocratic extraction to shifting domestic and regional dynamics. And those crimes would not have been possible without a wider regional context featuring an international cast of characters.

Click here to read this article, available open access for a limited time.

Claire Antone Payton is a postdoctoral fellow at the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African American and African Studies at the University of Virginia. She received her Ph.D. in History from Duke University in 2018. Her current research analyzes the intertwining histories of urbanization and authoritarianism through a history of construction in Port-au-Prince in the 20th century.