During an interview in 2014, Miguel Ángel Tobar, an assassin for the Mara Salvatrucha gang, asked Salvadoran brothers Óscar and Juan José Martínez—a journalist and an anthropologist, respectively—why they wanted to tell his story:

“‘Because,’ we answered, ashamed, ‘we believe that your story, unfortunately, is more important than your life.’”

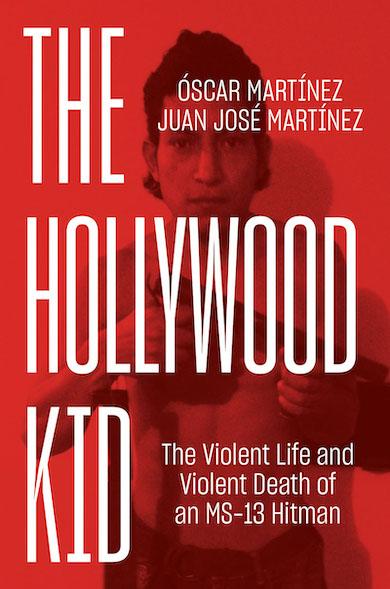

Tobar, a.k.a. “the Kid” of the Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha clique of MS-13 in El Salvador, would be killed that same year, but his story now lives on in the Martínez brothers’ masterful The Hollywood Kid: The Violent Life and Violent Death of an MS-13 Hitman, translated from the Spanish by John B. Washington and Daniela Ugaz. The book is based on years of interviews with Tobar when he was a “protected” (read: conspicuously unprotected) witness of the state after a falling out with fellow gang members who had killed his brother.

Tobar was born in the dusty town of Las Pozas in rural western El Salvador in 1983, in the middle of the country’s brutal civil war. At the age of 11, he attempted his first murder: the coffee plantation foreman whom his crippled father had permitted to repeatedly rape Tobar’s sister. At age 12, in order to seal his pact with MS-13, he killed and decapitated another youth, a baker from a small village who had pledged allegiance to the rival Barrio 18 gang. “They said the guy was a witch,” he told the Martínez brothers, 17 years later. “So that’s why I cut the dude’s head off, because they say that witches can put their brains back together.” It was all downhill from there, until he “fulfilled his own prophecy by getting murdered” as he was heading home from registering the birth of his second daughter.

The authors use the trajectory of this individual gangster—who killed more than 50 people over the course of his career, even removing one victim’s heart with his bare hands—as a vehicle to recount the country’s violent history. The book is nonlinear, an effective format for piecing together Tobar’s life alongside the national one. The timeline begins in the late 1800s, at “the moment we all went crazy in El Salvador”: when the government decided that the country would become fixated on growing for-export coffee on the backs of Indigenous folks performing slave labor after their lands had been stolen for the project.

The book extends through to the present day, with El Salvador’s intermittent distinction as the most murderous place on the planet and Donald Trump’s apoplexy over MS-13, a gang the U.S. created in the first place. Trumpian hysteria has sent the elite of Long Island scurrying to weaponize their wine cellars, while also giving a toxic boost to general xenophobia and justifying manic U.S. border fortification and deportation schemes.

In El Salvador, to be sure, life is cheap—and even more so, perhaps, if you belong to a demographic widely seen as uniquely evil, subhuman, and in need of extermination. That’s why, among other reasons, the Martínez brothers’ undertaking is so important. Not only do they humanize the Kid, they also show him to be a product of history and of “a long series of violent acts.” They depict him as a man whose “personal agency…had always been limited, always tied to distant decisions made by US and Salvadoran politicians.” As Tobar himself observed: “We were born of the war. We lived the war, and it was the people of the war that made these gangs.” Ultimately, when it came to joining the ranks of MS-13, he said, “They didn’t give me no other choice.”

The Salvadoran civil war ended in 1992. When Tobar joined up with MS-13 in the mid-1990s, unwittingly enlisting in what would become the country’s next protracted war, the Martínezes note, “the remains of the 75,000 victims of the other conflict were still smoldering.” Significantly, the blame for the majority of the bloodshed lay with the right-wing state and allied paramilitary groups and death squads backed by—who else?—the United States.

As part of its valiant quest to make the world safe for capitalism by terrorizing people, the U.S. ultimately “funneled something like $4.5 billion in aid to the Salvadoran government and military over a dozen years, coordinating with its leaders via the US Embassy in San Salvador and helping to cover up its crimes.” Of special interest on the cover-up front was the notorious 1981 massacre by the U.S.-trained and funded Atlacatl Battalion in the village of El Mozote, “where up to 1,200 civilians were slaughtered.”

During the war, countless Salvadorans fled north to the U.S., many of them to Los Angeles, where the American dream quickly proved not all it was cracked up to be. Young Salvadorans formed gangs as a means of communal self-defense. Well-represented among the incoming migrants were deserters from combat, whose battle prowess came in handy as the new gangs developed—meaning that, in a sense, “the counterinsurgency training that [Ronald] Reagan provided to the military ended up training future MS members as well.”

When peace accords ended the conflict in El Salvador, the U.S. undertook massive deportations of gang members, a policy the authors categorize as “a bad decision by US authorities, who thought they could solve a problem by expelling it.” Of course, it’s debatable how much imperial concern there ever really is for solving problems, particularly when the perpetuation of strife provides new opportunities for militarization and economic tyranny.

One civil war deserter was a Salvadoran “of indigenous descent,” a former soldier in the National Guard, who would eventually go by the alias Chepe Furia. Following a stint in a gang in California, he returned home to western El Salvador to found the Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha clique of MS-13. Like many, he capitalized on “a country full of kids desperate for a less miserable life”—kids whose “dream was not to be somebody rich, but just to be somebody. A different person from who they were.” One of the first recruits was Miguel Ángel Tobar.

The Martínez brothers emphasize that “MS-13 is a mafia, but it’s a mafia of the poor”—useful information, no doubt, in light of a prevailing opinion that gangs are simply endemically satanic rather than a result of complex social factors including economic oppression, obscene inequality, and state neglect. They offer Tobar’s story as a “microhistory, a perfect example of the human cost of these international processes” in a part of the world where “explanations…are in short supply.” For those of us raised on the reductionist drivel that passes for history and analysis in the United States—in which the U.S. is never the victimizer, even when it’s dropping atomic bombs or massacring pine nut farmers in Afghanistan—the pursuit of truth is a breath of fresh air.

During one meeting with Tobar, the authors asked him if he sometimes tells his wife Lorena and young daughter Marbelly that he loves them. “No,” he replied, “I mean, since I was little that wasn’t really in my vocabulary, you know. The thing is that they know I’m strong for them, that if anyone touches them the Beast’ll come out.” This, the authors reckon, “is probably the sweetest thing Lorena will hear from Miguel Ángel…a declaration of love in the midst of death.”

On November 21, 2014, death comes for Tobar. In 2018, the authors revisit his grave to find that someone else has been buried on top of him and that the cemetery manager is a former killer from the Atlacatl Battalion, who remains upbeat about the whole death squad era.

In life, the Martínezes write, the Hollywood Kid was “one of those rare individuals who does reflect, who bravely asks himself why, why, why?” Now, with El Salvador awash as ever in violent lives and violent deaths, it’s about time we asked why.

Belén Fernández is the author of Exile: Rejecting America and Finding the World (OR Books, 2019) and The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work (Verso, 2011). She is a contributing editor at Jacobin Magazine.