This piece appeared in the Fall 2020 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

When Covid-19 infections swept across Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest port and industrial hub, in March 2020, the poorest and wealthiest zones in the metropolitan area were the first to be hit. In Samborondón, for instance, home to the blanco-mestizo upper class, weddings and large, catered gatherings became superspreading events. Another outbreak tore through the Afro-Ecuadorian community of Nigeria in Isla Trinitaria, a mangrove-ringed zone on Guayaquil’s southwestern outskirts where mostly impoverished informal and domestic workers live in cramped intergenerational housing.

A nightmare scenario exploded across the metropolitan area. In a flash, ambulance and hospital infrastructures collapsed. Even more traumatically, the city’s privatized funerary and mortuary industries imploded under overwhelming demand. Death-care proprietors, who had long benefitted from nationwide decentralization of the sector, quickly reached maximum processing capacities. Long lines of automobiles with deceased family members in their backseats, or coffins tied down onto their rooftops, waited for hours or even days to bury their loved ones. But this was just the beginning of a rolling—and differently experienced—catastrophe.

By early April, most national and international news commentators viewed the crisis unfolding in the coastal lowland province of Guayas, where Guayaquil is located, as a cautionary tale about the untold human ravages of Covid-19. Local public health experts claimed that a few thousand had died, but testimonials suggested nearly a tenfold number of pandemic-related deaths. Real mortality rates were far worse than those of New York. Official narratives treated the catastrophe as if it were about the coronavirus alone. But global public health broadly reflects underlying conditions that are historical and political economic as well as corporeal and medical—or, indeed, biopolitical and necropolitical.

Guayaquil’s civic-managerial attempts to save lives also delineated private governmental decisions about who could be left to die, or, indeed, made to die. Municipal and private militarization of hospitals and cemeteries created a citywide archipelago of cordon sanitaire zones, but not—as is typically the case—to prevent people from leaving. Rather, security forces prevented loved ones and their medical advocates from gaining access to the dying or even the dead. Pandemic politics’ curious new institution—its carceral dynamic—emerged out of these circumstances in Guayaquil and quickly spread across the rest of Ecuador during the following days, weeks, and months in an unevenly distributed “sanitary emergency.” Today, Ecuadorian carceral worlds and their hidden-away logics openly influence health mandates and democratic governance of the living and dead as never before.

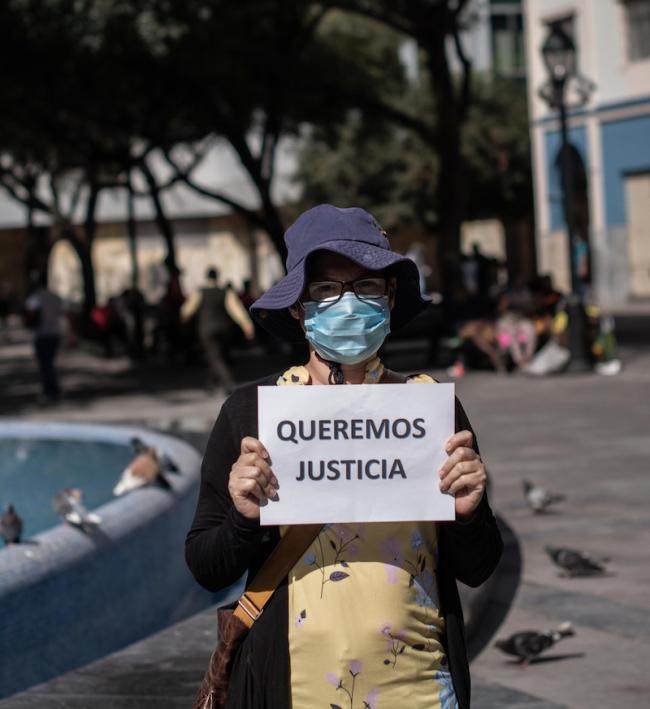

Reactionary state and police responses to the unfolding pandemic strongly call to mind the command-control governance under Ecuador’s military junta in the 1970s and the continuation of those policies during the infamous neoliberal 1980s and 1990s. Then, as now, governmental forces used mano dura policing in the name of protecting democracy or securing elite interests, with the backing of executive fiat and temporary suspension of civil liberties when needed. In the 1980s, former president León Febres Cordero deployed torture and forced disappearances to crack down a small leftist guerrilla. From then through the 2000s, leaders such as Febres Cordero and Jaime Nebot, who both served as mayors of Guayaquil with the conservative Social Christian Party (PSC), targeted petty drug traffickers with heavy-handed policing in a globalized “war on drugs.” Now, the government of President Lenín Moreno and Guayaquil’s mayor, Cynthia Viteri (likewise PSC), have also remade the politics of disappearance. The national government declared a public health emergency and imposed a curfew. Viteri introduced measures to enforce shelter-in-place isolation, mask-wearing, and physical distancing. But new forms of public health policing in Guayaquil—which entailed draconian measures for the urban poor—quickly enveloped a city already riven with extreme inequalities, civic abandonment on the urban peripheries, and a serially underreported mass incarceration problem.

As coronavirus cases surged across Guayaquil, urban citizenship unmoored and remapped itself in relation to both voluntary and obligatory confinement practices, differential geographical and class-based mobility (or lack thereof), and the literal disappearance of certain bodies unaligned with governmental interests—both in life as well as in death. A harbinger of things to come for Ecuador as a whole.

Organic Breakdown

Natural disasters typically accelerate or deepen longstanding political economic and sociocultural divides. Ecuador’s coronavirus emergency has been no different. For nearly 20 years, I have studied how mano dura policing in Guayaquil’s marginal neighborhoods and the normalization of mass incarceration led to a new urban political ecology—or to a mode of Christian majoritarian citizenship that also criminalized “anti-social” youths of color, remapping a newly segregated city into “saved” and “fallen” neighborhoods. Explaining similar urban processes elsewhere in South America, anthropologists Teresa Caldeira and Daniella Gandolfo have described, respectively, the “implosion of modern public life” in Brazil and the neoliberal micro-dynamics of “urban transgression” in Lima, Peru. Yet early in Guayaquil’s pandemic breakdown, most residents demanded immediate, across-the-board solidarity and cooperation in hopes that the emergency health measures could be uniformly observed.

City residents watched helplessly as 911 services became unavailable and their loved ones struggled without emergency medical support, taking final breaths and dying right in front of them. The corpses of one, then sometimes multiple family members accumulated in houses and apartments. As temperatures hovered between the upper-20s and lower-30 degrees Celsius (77-94 Fahrenheit) with high humidity in March and April, olfactory traumas built like a pressure cooker among surviving relatives, trapped by police in their homes with putrefying loved ones. National and international media latched on to the spontaneous, collective practice of families leaving their dead outside their living spaces in makeshift coffins or enveloped in plastic wrap. The smallest details of these images crushed me: a beachgoer’s parasol placed above the “head” of a plastic-wrapped body lying prostrate on a city bench; a swatch of beautifully embroidered cloth covering what was obviously a body bag; a corpse wrapped in an industrial-sized black garbage bag deposited right in front of my favorite coffee shop in Guayaquil. What media outlets initially failed to report was that such a pushing away of the dead for the most part took place in poor or underserviced districts, and these reports only made news headlines in late July. Families and sometimes whole neighborhoods floated untold numbers of bodies off into the city’s saltwater estuaries (esteros), or laid them to rest closer to home, allegedly—as rumors had it—in backyard burials. The poorest of working-class communities were already deeply suspicious of the state before institutions began to buckle under the crisis.

Read the rest of this article, available open access for a limited time.

Chris Garces teaches at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito. His ethnographic interests range from the study of politics and religion—or contemporary political theologies—to the unchecked global development of penal state politics and the history of Catholic humanitarian interventions in Latin America.