This article was originally published in Spanish in Avispa Midia, Aristegui Noticias, and Pie de Página, in alliance with CONNECTAS. The English language translation is co-published with Avispa Midia.

The Canadian-owned company Minera Cuzcatlán is the sixth-largest silver producer in Mexico. In 2018, a waste spill at one of the company’s mines impacted a stream in Oaxaca State.

The event sparked an intense controversy, documented by the media, over whether or not the mining waste had contaminated communities’ soil and water.

This journalistic investigation uncovers the original reports, which indicate the presence of toxic materials at levels that in some cases exceed Mexican standards by up to 1845 percent.

It also shows how Mexican authorities and the company kept these documents under wraps these documents in order to let Fortuna off the hook for the effects of its contamination in this region of southern Mexico.

Aquino Pedro Máximo vividly recalls the early morning of October 8, 2018, when a torrential downpour broke loose. Aquino is an Indigenous Zapotec farmer from the community of Magdalena Ocotlán, Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. On the night of October 7, he heard a deafening noise over the tin roofs of the homes in his village. Early in the morning, as was his custom, he grabbed his machete and set out to begin the day’s work on his crops, along with the other farmers. They were taken by surprise when they saw that the El Coyote stream was stained with a grayish material.

“It looked like cement,” Aquino recalls.

More than four kilometers of the stream had been covered with this gray mud. The water, which the campesinos use for agricultural and livestock purposes, was completely grayish, as was the vegetation and soil surrounding the stream. In the municipality of Magdalena Ocotlán, where Aquino lives, the muddy mass had spread around the area known as “La Ciénega,” home to the community’s drinking water well in addition to a water dam used for grazing animals. The nearby Zapotec communities of San Pedro Apóstol, San Felipe Apóstol, San Matías Chilazoa, and Tejas de Morelos were also affected.

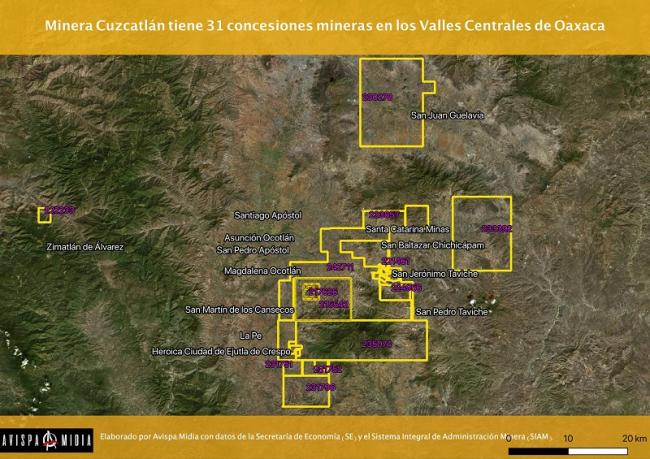

Minera Cuzcatlán, a subsidiary of Canada's Fortuna Silver Mines, is the sixth largest silver producer in Mexico. The company also produces gold to a lesser extent. As of 2020, the federal government had granted Cuzcatlán five permits for mining exploitation in the region. On the land covered by these permits, the company had drilled more than 300 kilometers (186 miles) of tunnels. Cuzcatlán holds an additional 26 mining permits that form a gold and silver mining corridor covering an area of 64,000 hectares (around 158,150 acres).

The mud that contaminated the El Coyote stream was a mixture of rainwater and waste from the mining process, better known as tailings. At the company’s facilities, dry tailings can be observed from a distance because they form an enormous gray mound, made up of a fine powder that looks like cement. The mining waste is also concentrated in liquid form in a large dam. Fortuna claims that these tailings do not pose any danger to the environment or to the health of nearby populations, even though they are the result of a process in which a range of toxic chemicals are used.

According to Fortuna, on October 8 heavy rainfall exceeded the capacity of the pool that captures rainwater and runoff from the tailings deposit, and which is around the size of three Olympic swimming pools. From this pool the dry waste is then pumped to a larger liquid tailings dam. In Mexican authorities’ case file on the incident, to which this investigative team had access, the company explained that “the pool’s two pumping systems were not sufficient to pump this water to the tailings dam, which caused the water to overflow.”

The spill sparked an intense controversy over whether the mining waste had contaminated the soil and water in surrounding communities. On the one hand, from the outset the company publicly alleged that its tailings are non-toxic and therefore there was no contamination. On the other hand, the communities denounced serious negative impacts to their territory.

Mexican authorities’ first official reports on the spill stated that Minera Cuzcatlán “dumped contaminants” into the El Coyote stream, “causing environmental damage.” The first analyses by an internationally respected British laboratory also identified contamination of the soil affected by the spill. However, Mexico’s National Water Commission (Conagua), the Federal Attorney's Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa), and Fortuna Silver Mines sealed these early reports indicating contamination. The effect was to deny that the El Coyote stream had been contaminated and to absolve the company of all responsibility.

The Water was Contaminated

Luz María Méndez Rodríguez is a mother from Magdalena Ocotlán, the community most affected by the spill. She is also the community’s Alderwoman of Finances. María narrates the days following the 2018 disaster. “Some of our animals began to die,” she says. “Children and older people began to have stomachaches, diarrhea, skin allergies. We were told there was an outbreak of Hepatitis. We had never experienced a situation like this before.”

Magdalena Ocotlán's Ecology Alderman, Oliva Odelia Aquino Sánchez, explains that because the gray mud reached the vicinity of the community’s drinking water well, residents decided to stop using this water. This situation, however, was not sustainable for long. “Everyone got worried and then we started to buy (bottled) water; many only held out for a few weeks. Then they went back to drinking that contaminated water, because it’s tough, there’s barely enough money to eat.”

In Mexico, a 20-liter container of water costs around one dollar. That residents are unable to spend more than that each week is largely because farmers do not receive a fixed salary; rather, each subsists on his or her own harvest. According to 2015 data from Mexico’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (Coneval), 73 percent of the population of Magdalena Ocotlán lives in poverty. Almost a quarter of the population lives in extreme poverty, according to information published by the Ministry of Welfare in 2021.

José Pablo Antonio, a lawyer advising the communities, says that according to international legal frameworks, until the situation is resolved authorities are required to issue preventive measures and provide communities with information. “They should have suspended the population’s use of water and guaranteed its supply from other sources until the situation was completely resolved. But that’s not what happened here,” he says.

Two days after the spill, while the communities were living in uncertainty, environmental authorities carried out an inspection of the affected areas. The National Water Commission (Conagua) was responsible for analyzing the water; the Federal Attorney’s Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa) was responsible for testing the soil. In each case, the authorities opened a dossier on the spill.

Water commission official and state laboratory personnel arrived to test the water. They confirmed that the spill came from the “pool that collects rainwater that washes away the soil and sediments from the dry tailings, and which are deposited and stored on higher-level terrain....The conduction of this runoff to the basin is done by means of a channel,” the officials detailed in their report.

While the Conagua technicians were working, it rained again, and they witnessed a new spill. According to the officials, the conduction channel was not able to withstand the added amount of rainwater mixed with mining waste. As a result, the edge of the channel broke: “This water, with the soil runoff and sediments from dry tailings, is observed to be grayish in color, flowing towards a road that leads to the El Coyote stream, where this runoff arrives and mixes with national waters,” the Water Commission report reads.

In the end, when there was a small lull in the storm, state laboratory personnel took samples “precisely at the site of the channel that collects soil runoff and dry tailings sediments.” During the same visit they took samples from the El Coyote stream.

The results of these samples were analyzed by two National Water Commission laboratories: the same South-Pacific Regional Laboratory that collected them, along with the National Reference Laboratory for Water Quality Management.

Heavy metals were identified. Their presence exceeded the levels permitted by Mexico’s national environmental agency. The presence of metals also meant that the water failed to meet the country’s quality criteria for agricultural irrigation and livestock uses. In the El Coyote stream, iron exceeded the permissible limits by up to 1845.8 percent, aluminum by 955.12 percent, silver by 591.2 percent, nickel by 173.915 percent, and lead by 167 percent.

In document number BOO.810.02.2455/2018, Water Commission officials state: “The rainwater that washes away the soil and dry tailings sediments does not comply with the maximum permissible limits established in Mexican official standard NOM-001-Semarnat-1996. It also exceeded the maximum levels established in the [Ecological Water Quality Criteria] published in the Official Journal of the Federation on December 13, 1989, which establish parameters for pH, Total Suspended Solids, and Chemical Oxygen Demand for bodies of water used for agricultural irrigation and livestock purposes. As regards heavy metals, they exceeded the maximum permissible limits for Aluminum, Iron, and Lead, contaminating the El Coyote stream.”

Conagua also claimed that there was “environmental damage” and warned that the affected water should not be used for agriculture and livestock. “As these contaminants exist in the Stream, the runoff from national waters that flow through the streambed cannot be used for these purposes,” the document reads.

However, authorities’ initial conclusions about the contamination of the stream changed over time, in response to new studies conducted by consultants and laboratories paid for by the Cuzcatlán mining company, subsidiary of Fortuna Silver Mines.

One turning point occured on November 27, 2018, when Conagua notified Cuzcatlán that it had opened a case file on the spill. The case file contained test results from the first water samples collected by government lab technicians. In a written statement, Conagua said that according to its studies the spill had contaminated the El Coyote Stream. As a result, the water authority ordered the company to carry out three urgent measures. The company complied with two of the measures, which required improvements to its facilities.

In an interview with our investigative team, Cristina Rodríguez, deputy director of sustainability at the Cuzcatlán Mining Company, said the company had “doubled the size of the water collection pool at our dry tailings deposit, from 7,000 to 14,000 m3, and quintupled pumping capacity to prevent runoff during the rainy season. We also built an emergency collection pool with a total capacity of 23,000 m3.”

The third measure ordered the company to evaluate the health and environmental risks of its tailings and to present a remediation plan to address these risks. Conagua gave the mining company an opportunity to conduct a new analysis of the affected area, thus paving the way for Fortuna to present new data on water quality and contamination.

The company presented its Program of Activities for the Remediation of the El Coyote Stream. The first action item was to collect new water samples to “determine the impact (...) and, if necessary, formulate the corresponding remediation program.” The National Water Commission accepted the company’s proposal.

Seventy days after the spill, a laboratory contracted by the company (Laboratorio Ingeniería de Control Ambiental y Saneamiento, S.A., de C.V.) took new water samples, which were analyzed by consultants of Cuzcatlán’s choosing (Nova Consultores Ambientales).

The new water samples were taken in a scenario that differed starkly from the October 8 spill. For example, there was no sampling in the rainwater and tailings runoff pool where the spill started, since the rainy season had already ended, and the pool no longer contained any water. Instead, technicians took samples from the El Coyote stream. Their studies concluded that the concentrations of heavy metals fell within permissible limits. In sum, the stream had not been affected. “There was no evidence of contamination of a body of water into which national waters flow,” the company said.

Based on this conclusion, Conagua fined the Cuzcatlán mining company $42,000 for failing to prevent the spill. “It is derisory,” said lawyer Claudia Gómez Godoy, a specialist in Indigenous issues and extractive industries. “These companies earn millions of dollars in a day; they can recover [that amount] in hours.”

The general director of Conagua’s South-Pacific Watershed Agency, Miguel Ángel Martínez Cordero, admits that the agency’s initial analysis found “contaminating elements that should not be there.” As a result, the mining company was allowed to do “what corresponds to its rights. Whatever is in their best interest.” When Cuzcatlán was granted the “right to reply, to defend themselves,” the company “sent us a series of documents,” says Martínez Cordero.

Subsequently, “we entered the remediation phase,” which is to say, “we had to know if there was something to remediate.” For this reason, Cuzcatlán “had to take new [water] samples.” According to Martínez Cordero’s version of the story, the sampling carried out 70 days after the spill “was within the administrative procedure, based on what the law says.” The contamination was no longer there because “the water flowed on and on and on.” He admits that the contamination did not disappear; rather, the contaminants merely migrated to an undefined “elsewhere."

For Omar Arellano Aguilar, a researcher at the Faculty of Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), specialist in eco-toxicology and member of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, timing is crucial for water sampling. Water samples must be taken as soon as possible after a contaminating event. This is because as rivers and streams flow, the metals they contain also move. These tend to accumulate in the soil surrounding the water. This means that while contaminants will be found in the water right after a spill, over time they will become trapped in the soil. For this reason, it is necessary to take several samples, not only of the affected water but also of the soil over an extended period of time.

According to biologist Martha Patricia Mora Flores, a research professor at the National Polytechnic Institute, the National Water Commission’s first studies provided sufficient evidence to conclude that the area had been impacted. Therefore, authorities should have implemented an urgent remediation plan for both the stream and the affected communities, as well as plan for monitoring the evolution of the contamination.

“Undoubtedly, the most reliable studies were Conagua’s,” she said. “What they did was to disqualify the analyses of a fundamental authority charged with protecting our water. If Conagua’s initial findings had been followed, the company wouldn’t have gotten off so easily, because they would have had to justify many things that they no longer had to justify with the new study.”

A Transcription Error?

Two days after the spill, technicians from the Federal Attorney's Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa) carried out an “ordinary inspection visit” to the Cuzcatlán Mining Company’s facilities. Their aim was “to verify, physically and through documents (...) that the company is complying with its environmental obligations.” In their inspection report they noted that the runoff pool has a gate that leads into the El Coyote stream. They also observed that “on the surface of the gate there is wet soil impregnated with gray mining tailings, which are also observed on the natural soil and weeds bordering the stream bed.”

No soil samples were taken during the inspection. In Profepa's opinion, the Cuzcatlán Mining Company was responsible for carrying out the corresponding studies. The company thus turned to the Intertek-ABC Analytic laboratory. Ten days after the spill, on October 18 and 19, technicians from this lab took 12 soil samples along the El Coyote stream.

The results identified thallium contamination in the soil at two different locations along the stream. One of these sites was in the vicinity of the community’s drinking water well. Based on the results of Intertek’s studies, Profepa issued a technical opinion confirming the existence of thallium contamination in the area.

In one of the plots of the land where the stream passes, thallium levels exceeded nationally permitted levels by 350 percent. Meanwhile, in the sampling site labeled as the “drinking water well,” thallium levels exceeded limits by 300 percent. Profepa wrote: “We conclude that there is soil contamination with the heavy metal Thallium at the sites named Parcel 1498 (Thallium 0.09 mg-L) and Drinking Water Well (Thallium 0.08 mg-L).”

The Cuzcatlán Mining Company tried to argue that it was not responsible for the presence of heavy metals in the soil. Not only did Cuzcatlán present various documents and reports to Profepa. The company also hired three different environmental consulting agencies to analyze the lab results documenting thallium contamination. Each analysis either disregarded the presence of this metal or argued that it did not represent a risk to the environment or to the health of the surrounding communities.

One of the consulting firms, Nova Consultores Ambientales, argued that since thallium concentrations in the Intertek samples exceeded permissible limits, a new sample collection was necessary. This was conducted by Grupo Microanálisis, which delivered the samples to Cuzcatlán. When Cuzcatlán brought the samples to Intertek for analyis, the lab’s technicians warned that the samples had not been properly preserved. However, the mining company authorized the study to be carried out anyway. In the case file on the spill, there is no document indicating that authorities questioned Cuzcatlán about the improperly preserved samples.

Whatever the case, the results from these samples no longer showed the presence of thallium. However, new metals appeared: barium and vanadium, which exceeded national standards by 50 percent and 72.9 percent, respectively. Nova justified that these could be due to “a local phenomenon and not due to the spill.”

In the end, Profepa disregarded all of the consultants’ analyses. This is because the Cuzcatlán Mining Company asked the Intertek laboratory to verify its initial results indicating thallium contamination. Intertek complied and concluded that it had committed an error in the data demonstrating thallium concentrations above national norms. The lab thus presented a new table in which the quantity by which the heavy metal exceeded permissible limits was replaced by the symbol “ND,” indicating that no thallium was present.

As stipulated in the case file reviewed by this reporting team, Profepa’s final report concludes that “due to an error (…) in the transcription of the results,” it was determined that the presence of heavy metals did not exceed permissible limits. “Therefore, it is concluded that there is no soil contamination and, consequently, no remediation is required.”

When our investigative team sought out Intertek's version of what happened, employee Diana Vásquez responded. The laboratory “has no press area as such,” she explained. “It’s a bit complicated if you don’t have a specific contact.” In the end our call was redirected to the company’s automated messaging system. We made another attempt to contact Intertek but were only able to reach the company’s voicemail.

According to the Cuzcatlán Mining Company’s deputy director of Sustainability, Cristina Rodríguez—as verified by the reports issued by Profepa and Conagua—“the runoff from our collection pool that occurred in October 2018 did not cause environmental damage, mainly because the Cuzcatlán Mining Company’s tailings are not classified as hazardous or toxic. However, the company maintains its commitment to environmental care and to a good relationship with the communities affected by the incident. In this way, the Cuzcatlán Mining Company has promoted agricultural and livestock development programs in the area, as well as reforestation, and frequent monitoring of water quality and the integrity of our facilities.”

The Polytechnic biologist, Martha Patricia Mora Flores, has doubts about Intertek's transcription error. “It is hard to believe a laboratory provider that’s a leader in total quality assurance for industries around the world would make such mistakes. The authorities should have reviewed the documents very carefully, especially because there were clear contradictions in the case.” Mora Flores explains that the only way to get clear answers would be to request “the raw lab results. To ask an independent expert to review and analyze the raw results, to prove that there was a typo."

We can’t believe “the company, just like that,” adds Claudia Gómez Godoy, the attorney. Rather, their word “must be guaranteed by means of tests, by means of new verifications.” Gómez Godoy emphasizes that Profepa is “the authority responsible for this and for taking care of environmental quality.” However, the case file shows the extent to which Profepa’s internal decisions were based fundamentally on “the documentary evidence provided by the legal representative of the Cuzcatlán Mining Company.”

The company submitted its documents to Profepa; the agency’s Legal Subdelegation received them and requested a technical opinion from its Subdelegation of Environmental Auditing and Industrial Inspection. This technical opinion was formulated on the basis of the documents and studies paid for by the company. It was then returned to the Legal area. This is how decisions were made, with technical opinions based solely on evidence presented by Cuzcatlán.

“No company is going to assume that it contaminated,” says Gómez Godoy. “These practices lend themselves to corruption.” According to the eco-toxicology researcher, Arellano Aguilar, the state has neglected its duty to carry out effective environmental oversight and enforcement. “The burden of proof falls on the companies, which have laboratories at their command,” he says. “There’s a conflict of interest; unfortunately, regulatory mechanisms have been designed just for that—so that there’s impunity.”

This investigative team requested an interview with the department of social communication at the Federal Attorney's Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa). Rubén Jiménez was in contact with us; however, we were never able to schedule an interview, and the agency had not replied to us by the time of the publication of this article.

The Eternal Suspense of Local Residents

The affected communities were never aware of the role the environmental authorities played in dealing with the October 8 spill, which negatively impacted their health as well as their access to potable water. “At no time did Profepa, as a public agency of the federal government, approach the communities to provide them with information,” says José Pablo Antonio, the lawyer advising the communities.

Aquino Pedro Máximo, the Zapotec farmer from Magdalena Ocotlán, insists that they were never informed of the presence of heavy metals in their water or soil. “We don't have money to pay for our own studies,” he says. “We don't trust the authorities either, because from the way they behave it seems as if they work for the [mining] company. They’re most concerned with ensuring the company can keep operating and they don’t care if we suffer.”

According to Gómez Godoy, the attorney and expert on extractive industries, a lack of information is characteristic of the violation of fundamental rights. “If people from the communities don’t have information about water quality then several of their rights are being violated. First, the right to information, but also the human right to water, to health. Information is fundamental to guaranteeing the other rights.” Gómez Godoy also points out that it’s necessary for Mexico’s environmental agencies, including “Semarnat, Profepa and Conagua, to adapt to the new reality of international human rights conventions, which are on an equal ranking with the Mexican constitution [since 1992].”

Federal environmental agencies also never warned local health authorities about the presence or possible impacts of the metals identified in the vicinity of the El Coyote stream.

Eiser Ariel Vázquez Salazar is the coordinator of the Medical Unit at the Mexican Social Security Institute in the community of Magdalena Ocotlán, where he has worked for six years. “These institutions charged with protecting the environment have never officially provided us with a protocol so that we know what measures to follow,” he says.

Efrén Sánchez Aquino, a municipal trustee of Magdalena Ocotlán who took office in 2020, is worried because many people got sick. “I had diarrhea and stomach pains for several days,” he says. “Today as an authority my concern is even greater because we have to watch over our community.”

The social security doctor, Vázquez Salazar, confirms that in recent years—and especially after the spill—he has noticed an increase in intestinal diseases, liver-related problems, oral diseases, and allergies, mainly of the skin.

This reporting team requested information from the Health Department in Magdalena Ocotlán about the types of diseases and number of cases registered in the municipality in the last five years. The municipal health authority stated that they have no such records. Instead, he directed the team to the municipality’s rural health unit—the same office coordinated by Vázquez Salazar. In an interview, Vázquez Salazar said that his health unit does not keep any systematized records of diseases in the municipality.

This investigative team also filed a request for information regarding diseases in Magdalena Ocotlán with the federal government’s Secretary of Health. The request turned up no records. When a request for information was filed with the Institute of Health for Welfare (Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar), the federal agency replied that the request was outside its scope of authority. Staff directed our inquiry to the Secretary of Health of the state of Oaxaca, which did not respond to the request nor pay attention to the complaints filed.

“We haven’t been able to get an assessment or study indicating the real impacts of the spill on our community’s health,” says Vásquez Salazar, the coordinator of the medical unit in Magdalena Ocotlán. He does not rule out a correlation between the increase in diseases in the community and the spill, as well as Cuzcatlán’s mining activity more broadly. “We found that substances from the mining process reached the community’s main water supply. This is a fundamental fact that we cannot disregard,” he concludes.

Meanwhile, the general director of Conagua's South-Pacific Watershed Agency, Miguel Angel Martinez Cordero, claims that they never informed affected communities about environmental and health risks because the responsibility to do so lies with the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat).

This reporting team requested an interview with the president of Semarnat’s Coordinating Unit for Social Participation and Transparency, Daniel Quezada Daniel. Daniel is also responsible for following up on the conflicts between communities and the Cuzcatlán Mining Company. However, Daniel never followed up on our request.

History Repeats Itself

Affected communities still do not know the true outcome of the 2018 spill. Yet environmental authorities have already closed the case file, as if they expected community members to simply forget about the negative impacts of mining on their soil and water. This has not been possible. As recently as July 13, 2020, residents of Magdalena Ocotlán detected a new case of contamination.

When the shepherds of the community brought their cattle to drink water from a storm water collector—located less than 300 meters from the mining company’s facilities, on the banks of the Santa Rosa stream—they noticed that the water had a reddish color with a white streak.

The shepherds notified their town authorities, who filed an official complaint with the Federal Attorney’s Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa). The Cuzcatlán Mining Company immediately stated that there had been no spill and disclaimed any responsibility.

The environmental authorities again conducted water and sediment studies. Two months later, Ernesto Faustino González Vázquez, head of the National Water Commission’s environmental impact project in Magdalena Ocotlán, came to the community to physically deliver a summary of the results. This investigative team was present at the site.

Magdalena Ocotlán’s Alderman of Public Works, Francisco Rosario Valencia, asked González Vázquez whether or not there were heavy metals in the community’s water supply. The official replied: “We put those that exceed the limits in bold (...) there are no heavy metals, aluminum is the one that’s above [the limit].”

When the official was asked if he knew about the health impacts of high aluminum concentrations, he replied: “I’m not a doctor, I just know that it’s over [the limit].”

The technical report, to which this investigative team had access, showed the presence of aluminum up to 25,900 percent over the Ecological Water Quality Criteria for the protection of aquatic life in fresh water. Iron exceeded the same criteria by 900 percent and Ammoniacal Nitrogen by 413.33 percent. Meanwhile, the percentage of dissolved oxygen was found to be below the ideal range, “indicating a lack of oxygen that limits the use [of this water] for the protection of aquatic life.”

The official documented presented by the National Water Commission exempts the Cuzcatlán Mining Company of all responsibility for water contamination, based solely on an on-site inspection of its facilities: “With the data obtained during the inspection visit and the water samples from six sites (in the water collector), it is not possible to establish that the agent causing the probable contamination is Minera Cuzcatlán,” the report reads.

By the date of this article’s publication Profepa had not made the results of the sediment studies public. The case file for the July 2020 incident remains open. Yet history is repeating itself. As environmental authorities and the mining company make decisions about this latest episode of contamination, community members are once again being kept in the dark, deprived of crucial information regarding their own health and territory.

This investigation was conducted for Avispa Midia, Aristegui Noticias, Pie de Página and CONNECTAS with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ), in the framework of the Investigative Journalism Initiative of the Americas.

Research: Renata Bessi and Santiago Navarro F.

Design and Programming: Pablo Angel Osorio.

Photo and Video: Santiago Navarro F.

Translation by Samantha Demby.