EcuRed, the state-run Cuban encyclopedia, describes José Lezama Lima as “one of the greatest figures” of the island’s literature, a writer of “astonishing erudition” who “constructs his phrases to perfection.” But, as the new PBS documentary Letters to Eloísa recounts, whereas Lezama was admired across the rest of the Spanish-speaking world, it wasn’t until twenty years after his death that he was officially recognized in Cuba. Indeed, towards the end of his life, the state banned Lezama from publishing, prevented him from collecting prizes overseas, and even censored any mention of him by other writers.

Using Lezama’s correspondence with his sister, who moved to the United States in 1961, Letters to Eloísa provides a short but intimate view of a baroque writer whose life overlapped with a period of great upheaval in Cuba.

The son of a colonel, Lezama was born into an upper-class Havana family in 1910. His father died from influenza when he was eight, and the young Lezama found comfort in books. By 1929, his mother’s source of income, a widow’s army pension, could no longer sustain a well-to-do lifestyle. The family were forced to move from the grandeur of the Paseo del Prado in the old town to a much smaller, humid house in Centro Habana, one block from the red-light district. It was here that Lezama would live until his death in 1976, and compose his major works of poetry and his one novel, Paradiso.

Lezama studied law at the University of Havana, but his vocation was to the Spanish language. In 1944, Lezama co-founded Orígenes, a literary magazine that gave rise to a new generation of Cuban artists. Widely read across Latin America, Orígenes folded in 1956 after Lezama fell out with its principal financial backer. Just over two years later, Fidel Castro came to power.

Although he preferred classical, theological, and literary themes to politics, Lezama—like most intellectuals—warmly greeted the revolution. Fidel Castro brought international attention to Cuba and, by extension, its literature. The state provided new opportunities for writers but, as Lezama would find, these opportunities came with political demands.

These demands became clearer in the months after the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 when, in a speech to Cuban intellectuals, Castro pronounced: “What are the rights of revolutionary or non-revolutionary writers and artists? Within the Revolution, everything. Against the Revolution, no rights at all.”

The threat of censorship was not Lezama’s only concern. His letters to Eloísa reflect the growing scarcities on the island. Lezama asks for razors, talcum powder, typewriter ribbons, sheets, and shoes. He laments that there are no beans, no tubers, no fruits.

“An onion skin,” he writes, with typical refinement, “can be as rare as an Etruscan coin.”

In 1964, a few months after his beloved mother died, Lezama—a closet homosexual—married his secretary, María Luisa. Two years later, he published his only novel, Paradiso, a story of an aristocratic Havana family, and of the city itself. Lezama described it to Eloísa as concerning “the exaltation of the family, the birth of the eros, the leaning into infinity.” The novel was praised across the Spanish-speaking world, most notably by the Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar. Interviewed for Letters to Eloísa, Mario Vargas Llosa describes Paradiso as “a novel of a great poet, a great connoisseur of the language, in which, frequently, the style is more important than the narrative.”

Instead of attracting readers for its linguistic opulence, Paradiso quickly became famous—or infamous—for a homoerotic scene. Cubans went to the library to borrow “the book with Chapter 8.” It also drew the attention of the censors.

According to historian Lillian Guerra, “Paradiso was Lezama’s personal coming out.” With Castro’s government sending homosexuals to rehabilitation camps, even promoting homosexuality using the mask of literature was brave. Lezama was seen to endorse “degenerate behavior” that Castro had said a socialist society could not permit. Domestic sales of the novel were suspended.

Lezama’s relations with the state improved in 1970. Two years after the Cuban government received criticism for supporting the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the state sought to improve its reputation by creating more space for artistic expression. Lezama was feted as a singular literary voice and was able to publish his complete poetry.

The freedom was soon retracted. The trigger was the Padilla affair: in 1971, Heberto Padilla, a poet critical of the revolution’s path, was arrested after a public reading of his work. In a televised confession, Padilla—who had been tortured in prison—thanked his interrogators and described his previous work as counter-revolutionary. More seriously for Lezama, Padilla accused him of being ungrateful to the revolution and of criticizing it in private.

The Padilla Affair marked the end of the government’s partial acceptance of creative freedom. It was also the beginning of five years of intense stress for Lezama, who told Eloísa how he lived “in fear, overwhelmed.” These were “anguished days,” especially after the 1971 Congress on Education and Culture decreed homosexuals a threat to Cuban values. As both a freethinker and a suspected homosexual, the author of Paradiso was prevented from publishing.

Lezama may not have been able to participate in Cuban intellectual discussion, but in 1972 critics in Madrid awarded him the Maldoror Prize—one of the most prestigious awards for Spanish-language poetry. Two years later, with the help of the acclaimed translator Gregory Rabassa, Paradiso was published in English.

When Lezama died in 1976, the news made headlines around the Hispanic world. But n Cuba’s main newspaper, Granma, it was only noted in passing. Lezama’s official standing on the island changed twenty years later, after the fall of the Soviet Union, when Cuba invested in tourism as an economic lifeline. In 1994, the state converted Lezama’s home,where he wrote all of his important works and where he was put under watch,into a museum. While it is refreshing to see Lezama granted due respect, it remains ironic that a government that censored one of its greatest writers, intercepted his correspondence, and wiretapped his telephone, now claims him as a national treasure.

Letters to Eloísa airs at a time when the Cuban state is embroiled in another major dispute with intellectuals. Members of the San Isidro Movement of free-speech activists have been arbitrarily detained, placed under house arrest and had their channels of communication blocked. Last month, Time magazine named one member, performance artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, in their list of the hundred most influential people in the world. Notwithstanding his baroque sensibilities, Lezama, whose poetry is read at protests, is a touchstone for the movement.

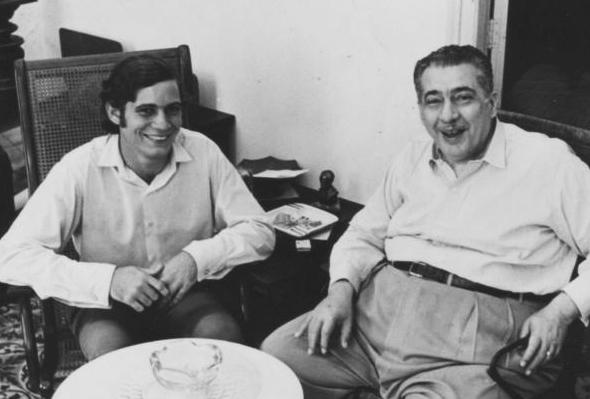

Running at sixty minutes, Letters to Eloísa is more of a sketch than a portrait. Nonetheless, using archival photographs, television footage, and small-scale re-enactment—not to mention his own words—the film is a welcome introduction to Lezama, and an outline of a history the Cuban government would rather forget.

The film premieres as part of the PBS series VOCES on Friday, October 15, 2021, from 10:00-11:00 p.m. ET on PBS, pbs.org and the PBS Video app.

Daniel Rey is a British-Colombian writer and historian.