This article was originally published in Portuguese by Agência Pública.

The year was 2016, then the hottest on record. Concerned by the impacts of global warming on soybean farming, Brazil’s then-agriculture minister, Blairo Maggi, invited the scientist Carlos Nobre to meet with the board of Amaggi, the minister’s family business and one of the country’s largest grain exporters. Nobre had been asked by Maggi to give a talk on how much scientists already knew about the potential impacts of climate change on agricultural production, with a particular focus on the Amazon region.

Nobre, one of Brazil’s most renowned climatologists and one of the foremost experts on the Amazon region, set about preparing for the job thoroughly. He talked to fellow researchers, poured over dozens of papers on the subject, and drew up the talk he would deliver to the board of soybean producers.

“I demonstrated that changes in climate could render the whole southern region of the Amazon and northern part of the Cerrado [where the company’s soybean plantations are located] practically impossible for the continuation of productive agriculture because of excess heat,” Nobre said.

The scientist explained how temperature highs above 40ºC (104ºF) could become commonplace in the region. “At these temperatures, the productivity of soybean crops is extremely low,” he said. He further warned those in attendance that climate change greatly speeds up the frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts, which were already being recorded in the region and were tending to become more serious with each passing event.

Upon wrapping up his talk and opening the floor to questions, Nobre was left surprised. “A number of people put their hands up and all spoke about how there were no such problems, that soybean crops’ productivity increases under higher temperatures—which is completely false—and that climate change is not taking place,” he told Agência Pública.

It was only some time after that the scientist came to understand the source of his audience’s disbelief. “All of those soybean producers had previously listened to the climate-denialists Luiz Carlos Molion and Ricardo Felício [who had also been invited to give a talk].”

Molion and Felício are two of Brazil’s foremost exponents of a small but vocal group with ties to the academic world who deny that the planet is heating up or that human activities are capable of causing such impacts. They also question the role of the Amazon rainforest in the distribution of rainfall in Brazil, the extent of the Amazonian forest fires, and even claim that deforestation has no impact on the climate.

For decades, figures long opposed to the scientific consensus such as Molion and Felício have had little prominence in public debate. This, however, has changed in recent years. On top of touring the country at the invitation of agribusiness associations to give talks and spread the myth that global warming does not exist, they have also been elevated to the status of experts by the Brazilian Congress’s influential bancada ruralista (rural lobby), whose members have even invited them to address the Senate’s foreign affairs and environment committees. They have also gained exposure on media platforms linked to agribusiness interests and far-right politicians.

The perception of scientists and researchers interviewed by Agência Pública was that part of the agribusiness industry in Brazil has become resistant to any kind of serious discussion around the climate. Climate denialism has been incorporated into the far-right’s disinformation efforts and gained traction in rural circles, which have become fertile terrain for such denialism and environmental disinformation.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one business leader from the agribusiness industry told Agência Pública that denialist talking points have “permeated like a mantra” in the sector, particularly among farmers. The source added that this has had a direct impact on the sector’s political representation, particularly through the Parliamentary Front for Agriculture and Livestock.

“As they [ruralists] go on winning everything [in Congress], they don’t need any technical basis [to work from]. Since it has a lot of political power, the sector is stuck. No one is actually developing public policy. The only ‘science’ that they use is that which serves [the interests of] the lobby. Anyone who wants to develop science-based public policy is seen in a negative light, as an ‘environmentalist’. And as long as the sector doesn’t believe [the science], it doesn’t change, it doesn’t adapt and it ignores other possibilities.”

Tracking Down Disinformation

Over the course of two months, Agência Pública worked with the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s Laboratory of Internet and Social Media Studies (NetLab/UFRJ) to analyze promoted posts on Meta social media platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram, as well as YouTube videos and other content published on social media platforms, news websites, and other web pages. The aim of the study was to track down who was behind the spreading of climate denialism and environmental disinformation in Brazil.

The investigation traced the disinformation back to three primary sources: Ricardo Felício, a professor of geography and the University of São Paulo; Luiz Carlos Molion, a meteorologist and a former lecturer at the Federal University of Alagoas; and Evaristo Miranda, an agronomist who recently retired from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), a body affiliated with the country’s agriculture ministry, and who became the environmental guru of former president Jair Bolsonaro.

On top of being invited to give talks by a range of agribusiness associations, these individuals have also been given platforms on digital channels linked to the industry and the Brazilian far right. Miranda and Felício, for example, work as columnists and are often quoted as sources in reports for Revista Oeste, a conservative-oriented magazine founded in March 2020 that describes itself as “the first content platform 100 percent committed to the defense of capitalism and the free market.” The publication’s team is made up of a host of journalists who dedicated themselves to defending Bolsonaro’s administration over the course of his term in office.

Molion, meanwhile, is a frequent collaborator with Notícias Agrícolas, a news site that describes itself as “one of the most important media outlets of Brazilian agribusiness,” offering “direct communication with rural producers.” Despite the site claiming to be “a space with a rich diversity of opinions and information,” an advanced search on Google carried out by Agência Pública found 250 mentions of Molion’s name, while little space was afforded to researchers who take the issue of climate change seriously. By means of comparison, Carlos Nobre’s name appeared just 29 times.

Notícias Agrícolas has also published a letter by Molion, Felício, and other climate denialists that was written at the start of 2019 and called for the recently inaugurated members of Bolsonaro’s government to take a stance against “the positions held by environmentalist who argue in favor of measures that restrict the economy in an effort to minimize the effects of ‘climate change,’” with the authors claiming that such beliefs were held because of ideological, rather than evidence-based reasons.

Molion and Miranda have also frequently appeared on Canal Rural, one of Brazil’s foremost television channels dedicated to agribusiness affairs. Miranda is also a columnist for agribusiness-focused channels owned by Grupo Bandeirantes, one of Brazil’s largest media conglomerates, and is a frequent interview guest on the group’s new channel.

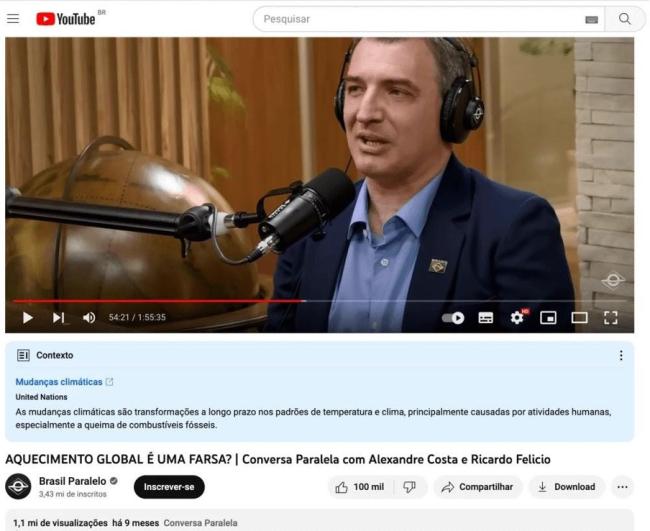

Felício, in turn, has a constant presence as a talking head on right-wing programs on YouTube. One interview he gave in August last year on a program produced by Brasil Paralelo, in which he claimed that “global warming is a lie,” had reached more than 1.1 million views by the publication of this report.

Brasil Paralelo, a producer of conservative-leaning documentaries and programs that hopes to become the “Netflix of the Right” has become one of the main platforms for spreading disinformation in the country, according to specialists who have researched the issue. When it comes to social and environmental issues, one of Brasil Paralelo’s most damaging pieces of content is the documentary “Cortina de Fumaça” (Smoke Screen), released in 2021, which denies deforestation of the Amazon rainforest while arguing that “a lot of fuss” is made about forest fires.

A Socioenvironmental "Infodemic"

Between March 31 and June 27 this year alone, Agência Pública counted 31 media appearances by the three climate denialist scientists, including weekly columns, interviews, and live events. The dissemination of this content, however, goes far beyond the individuals in question, and has been taken up by political representatives from both the Lower House and the Senate who form part of the Parliamentary Front for Agriculture and Livestock. The Front is a grouping of politicians from a range of parties who represent agribusiness interests, and it is the largest parliamentary caucus in Congress. Social media influencers with ties to agribusiness and the far right have also taken up the scientist’s talking points.

The strategy has been dubbed by the team from Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s NetLab as a “socioenvironmental infodemic.” In this infodemic, disinformation regarding the environment has become “one of the main focuses of the Brazilian far right’s political propaganda, being used to argue in favor of stripping back environmental protections and for the systematic advance of extractivist activities in Brazil,” the group wrote in a report that looked at the public discourse on socioenvironmental issues during the final two years of the Bolsonaro administration, from January 2021 to November 2022.

In general terms, the researchers found instances of politicians and influencers endorsing climate-denialist theories and defending the Bolsonaro government’s action on environmental issues. During the run-up to last year’s elections, the most prominent talking points were about the positive nature of the activities of Brazilian agribusiness and arguments that disputed the extent of the deforestation taking place in the Amazon.

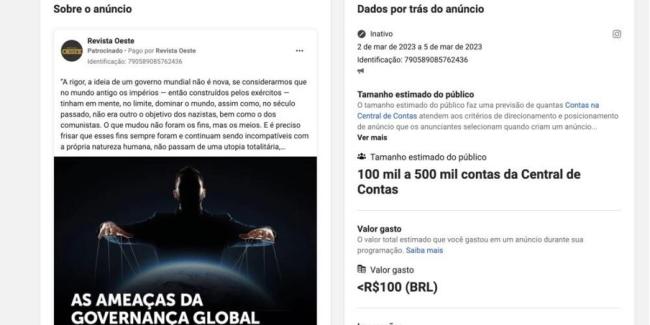

Agência Pública also commissioned NetLab to analyze social media posts from the first few months of 2023, paying particular attention to disinformation being shared in paid promoted posts, which reach “the most vulnerable audiences on these platforms in a systematic and targeted way.”

A lack of legal regulation means that transparency with regard to paid-for and promoted content is still sorely lacking in Brazil. Google and Meta are the only two companies to hold publicly available archives that show what paid content has been shown in Brazil, although “there are still serious gaps in data transparency that, [if it were to exist], would enable those who published false and often criminal content to be held accountable,” NetLab wrote. YouTube, for example, continues to make money from paid promoted content, despite having a policy that aims to stop the sharing and spread of content which espouses climate denialism on its platform.

On both Meta and Google, NetLab’s researchers identified promoted content and adverts which had been paid for by organizations, political candidates, and sitting politicians with links to agribusiness.

NetLab’s researchers divided the promoted content into two categories, both capable of producing misconceptions about environmental issues: promoted posts promoting conspiracy theories that present all environmental issues as alarmist or as being exaggerated by “climate fanatics,” and promoted posts that present an “alternative science” as opposed to science that points to serious levels of deforestation and climate change.

“They don’t directly question the scientific evidence, rather they portray the climate emergency as though it was mere politicking or a manipulated narrative to cover up the ‘globalist’ interests of NGOs, media outlets, and foreign governments,” NetLab’s researchers explained. “In order to discredit a talking point based on scientific knowledge, these promoted posts try to drag the battle for public opinion outside the field of science, as though what is at stake is not evidence, but rather the narratives themselves,” they added.

When it comes to “alternative science,” the NetLab team highlighted the occurrence of promoted posts that “claimed that there is no link between Brazilian agribusiness and the destruction of the Amazon biome or any other,” which flies in the face of the vast majority of research on the topic.

One illustrative example of this type of content was a post made by a congressional candidate in the 2022 elections who claimed that Brazil’s farmers and livestock-raisers supposedly protect an area of rainforest equivalent in size to 16 countries, going on to invite the public to “fight back against the lies that have been spread about agribusiness.” The politician in question paid Meta between 500 and 599 Brazilian reais ($100-120) to promote the post, which was viewed between 150,000 and 175,000 times. The same language also appeared in an advertisement posted by Brasil Paralelo on their Meta social media accounts.

The figure at the center of the claim was taken from a study by Evaristo de Miranda. The research paper has become something of a “Bible” for those in the world of agribusiness, but has been roundly criticized by other scientists working in the same field, who have accused Miranda of distorting calculations and generating false controversies.

Another figure shared by Miranda—which went on to appear in a senator’s promoted posts—is the claim that 66 percent of vegetation in Brazil remains intact. This is one of the most widely touted figures by the rural lobby and other industry supporters. The figure in question relates to a distorted interpretation of a real data point. Around 66 percent of Brazil’s territory is covered by vegetation, but it is a long way from being considered intact or “just as Pedro Álvares Cabral found it when he arrived in Brazil [in 1500]," as interviewees in Brasil Parelelo’s Cortina de Fumaça documentary put it.

Studies involving analysis of satellite imagery have shown that a large part of remaining areas of vegetation have already been subject to some form of degradation. A study by the State University of Campinas published in Science journal at the start of 2023 showed that in the Amazon alone, nearly 40 percent of the remaining rainforest has already been subject to some form of degradation, which reduces its capacity to provide all its environmental services, as well as making it much more vulnerable to forest fires.

The Attack on Science Underpinning Environmental Laws

Jean Miguel, a sociologist and associate professor in the Department of Political Science and Technology at the State University of Campinas’s Institute of Geosciences, has analyzed the relationship between climate denialism and what he calls “the impediment of environmental governmentalization in Brazil.”

Miguel argues that there is a historical relationship between agribusiness and certain values held dear by the far right, such as patriotism, sovereignty, religiosity, and support for the right to bear arms. He also argues, however, that there is a very pragmatic side to this incorporation of environmental and climate denialism.

"It’s a way of sowing ignorance that has been designed to target specific environmental laws. Not all science is attacked by the denialists, rather [they specifically attack] the science that is part of the regulatory process of environmental legislation and international agreements,” he told Agência Pública.

“Climate change is of no interest to the [agribusiness] sector when it reinforces the need to take action against deforestation or to tighten rules regarding environmental protection on [their] property,” Miguel added.

According to Miguel, such discourse has already gained traction at other points in recent history, but denialists found “fertile ground” in Bolsonaro and his supporters. “Denialism becomes legitimized as a scientific narrative. In the world of science they have no legitimacy, but in coming into contact with the world of agribusiness they acquire this legitimacy,” he concluded.

The Other Side

Every person, media outlet, and institution cited in this report was contacted for comment by Agência Pública. However, only a small number responded.

In a statement, Grupo Bandeirantes said that the conglomerate’s media outlets “are always open to hearing the most diverse opinions from all sectors, while constantly offering wide-ranging and diverse coverage. Evaristo de Miranda is a contributor to the subscription-based TV channels, just like so many other professionals who express their different points of view.”

Molion replied by saying that he did not have the time to respond to Agência Pública’s reporters because he was due to give a lecture, adding: “Who knows, perhaps at another point when I have time available. I think you should look at these issues with a more critical eye and not accept everything that you hear. Good luck!”

Brasil Paralelo got in touch with Agência Pública asking for more information about the content, but said they preferred not to comment.

Agência Pública has a biweekly newsletter in English. Subscribe here.

Giovana Girardi is head of social and environmental coverage at Agência Pública. As a journalist, Girardi has covered science and the environment since 2002.

Cristina Amorim is a journalist who has covered environmental and climate issues for 20 years.

Álvaro Justen is a programmer, educator, and free software activist. He is the founder of the accessible open data portal Brasil.IO.

Rafael Oliveira is a journalist who has worked since 2019 for Agência Pública, where he has produced award-winning reporting.