This interview is part of a series of interviews and articles in collaboration with Earthworks on the impacts of the oil and gas industry in South America.

In 2022, the Hidroituango dam opened in the Colombian department of Antioquia, near the town of Ituango along the Cauca River. With a reservoir the size of 8,000 Olympic swimming pools, the mega-dam now produces 17 percent of the country’s energy—but not without controversy. In addition to raising significant environmental concerns, the project highlights the connection between megaprojects and endless war in a region hard hit by decades of armed conflict.

“One condition in Colombia for hydroelectric power plants to be developed is the armed conflict,” explains Juan Pablo Soler Villamizar. “More than 100 massacres occurred in the Hidroituango area.”

Soler Villamizar is a member of the collective Communities Sowing Territories, Water, and Autonomies (Comunidades SETAA), a national initiative created in 2019 after years of analysis and mobilization within other national and regional environmental groups and networks. His work is focused on the problems brought about by hydroelectric dams, as well as the contamination of rivers and watersheds. This led him to study the energy model in Colombia, and in particular to ask questions like: Is a dam necessary? What is the role of a hydroelectric plant within the energy model?

This interview seeks to highlight the project arising from this collective reflection, especially the transformative and social fabric-building role of “community energy.” This idea contrasts with the government’s concept of “energy communities,” which emphasizes more top-down methods of community participation as a means of financing local infrastructure projects.

I spoke with Soler Villamizar on January 29, 2024, by Zoom. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity and translated from Spanish.

Patricia Rodríguez: Can you tell us a bit about your work, particularly with Comunidades SETAA?

Juan Pablo Soler Villamizar: We work on the climate crisis from two perspectives. One is the one that everyone talks about, that is, the crisis derived from climate change that alters the temperature at a global level; the other is what we call local climate change. This is the one that megaprojects make us feel in our bones.

I always say: living in a place seriously affected and aggravated by climate change is not the same as living in a city where the effects are felt indirectly. In the case of hydroelectric plants, Hidroituango, for example, caused the loss of 4,500 hectares of eco-tropical forests and put an ecosystem at risk of extinction. Now what we have in Colombia are patches of unconnected eco-tropical forests. If we understand that the reservoir is a 4,500-hectare mirror that receives and reflects sunlight to all sides, we understand why the temperature there rises more quickly than the global average. We see the effects in the production of eggplant, for example, in places that previously were too cold to grow it. Coffee, which is very fragile, is also affected by solar radiation.

But there is also another delayed effect, which is the change in relative humidity, or the water vapor trapped in the air. There is a big difference between the wind running through the canyon of the Cauca River of 20 to 30 meters [in length], dragging [the air], versus a mirror of 4,500 hectares. We saw this with Hidroituango, with Hidrosogamoso [dam on the Sogamoso River in the department of Santander], and elsewhere. For me, that was a very big warning of what was to come. Based on our experience in Colombia and that of other countries, we are also linked up with the entire movement of people affected by dams in the Americas, and we have been able to share experiences. We have seen that hydroelectric dams do not end when they are built.

In fact, when construction ends is when all the impacts come, and those impacts are like a fever in the body. We knew that the climate was going to change, in some parts more than in others, and that productivity was going to change. That brings drastic effects on the economies of individuals, but also on the economies of the municipalities.

In terms of achievements, we cannot say that we brought mayors and councilors into our movement, no. But we did change consciences, or sowed the seeds of cultural transformation, which is what is required to confront the climate crisis, starting from my location or body, my family, and then on to the neighborhood, and from there outwards. This is all part of community energy.

That’s the background and origin of this discussion, which is closely associated with the conflict brought about by the hydroelectric plant and how from there we tried to generate a proposal for a new energy model that does not have dams but meets the needs of local and, of course, national populations.

PR: In Antioquia, has there also been a big impact with respect to the presence of the oil and gas industry?

JPSV: Where we live, there is no oil and gas exploration left. In the eastern part of Antioquia, there are generally mining or hydroelectric projects, and because it is a mountainous area, oil and gas exploration are not so advanced. Colombia has 18 sedimentary basins and has exploited six of them. The rest are in the mountains, and that makes the business very expensive, and that is why it is not done here. But in the long term, let's say, it could happen.

What is certain is that we are affected by the use of fossil fuels. The appearance of the diesel engine allowed machines to open up new practices and generated a dependence on other machinery. This introduced a petro-addicted culture, and community work was lost. So, if you ask me, are you affected by oil activities? Yes! In addition to climate change, it’s because of all this cultural contamination that has resulted from the imposition of this culture.

PR: Do you collaborate with communities impacted by these and other industries or problems, not only those impacted by hydroelectric plants?

JPSV: The main process we have focused on is training, and we have started it together with other organizations such as Fundaexpresion in Santander, and at one time with ASPROCIG (Association of Fishers, Campesinos, Indigenous and Afro-Colombians of the Ciénaga Grande) in Bajo Sinú, where the Urrá dam is located, and with Censat Agua Viva. We started a training process based on exchanges of experiences.

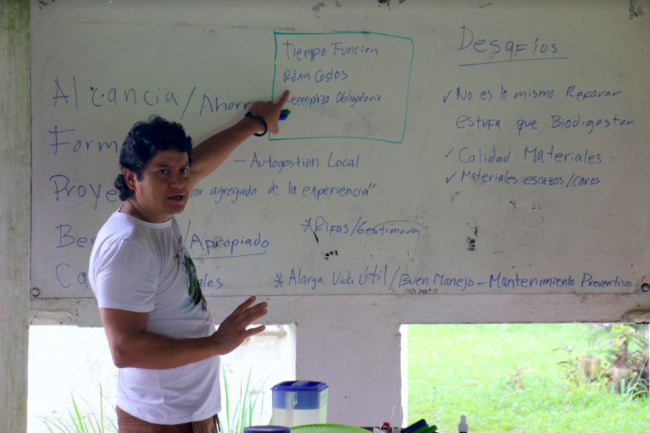

In 2013, I knew that efficient stove and biodigester were being installed. There is a principle that we follow and that is to not generate [new] dependencies. I want to plant seeds. So, we proposed exchanges of experiences among the communities that already had these installations, and after that, a training process around what we called at that time alternative energies.

We didn't know what to call them at first. We went back and forth between alternative energies, then renewable energies, then we found out the government's term is NCRE—non-conventional renewable energies. And so we said, no, that’s very much against the people! The School of Community Energy offered the possibility of maturing this idea and learning, creating knowledge and experience and spreading them throughout the territories so that people could become disseminators, or promoters. There is an article I wrote on the subject called “The energetic ubuntus.” I prefer [that concept] more than the figure of the prosumer, which seems to me to be very comfortable for those who don't want to solve the climate crisis but want to make a living from business.

I believe that we must create energy ubuntus, which is the idea that the people take ownership of the management and training of the energy model in all its dimensions, including the paradigm of society they want to build and transform. [Formally] we call it the School of Community Technicians in Alternative Energies.

We began to build biodigesters, efficient wood stoves, and solar dehydrators. These three technologies were the easiest to learn because of the knowledge already found in the communities. The fallout of the war means that there are people who have not gone to school, or don’t know how to read, or have only completed fifth grade, or are afraid, or think this isn’t for them. We also are looking into solar panel technologies for electricity production.

And around these four technologies we were forming communities and training people, and taking the knowledge to communities, but above all trying to ensure that this conversation did not remain purely technical. That is the challenge of all this. We have to transform the paradigm of society, which also has to do with the roles we have in the home. Community energy is a very nice idea, but we have to understand that this means truly changing society.

At the beginning, all the people involved were men, but now most of them are women, because they understand that it is a space for them, and that community energy efforts are led by the women in their homes. This is often invisible, but it brings in very important income. When we did the math on the biodigesters, we saw that in one year the biodigesters saved $72,000 pesos on gas (~$18, at the current exchange rate). That is a direct contribution by women to the household income, which is called “avoiding outlays.”

We group community energy into the categories of harvesting sunlight, water, new relationships, and human energy. With the biodigesters, the sun helps to transform [waste], so it is a harvest of sunlight, as with solar panels and solar heaters. With the water harvests, the Santander groups have collector roofs, but we also see that, in the Bajo Sinú, people cross rivers without the need for a motor. Other examples are those who go fishing by sail and the use of the Archimedes screws that some former FARC guerrilla communities set up [as power generators].

The last two categories are the most important in terms of the community fabric. Human energy is like the helping hand, the borrowed arm—there are different ways of calling it. In Brazil it is mutirão; Indigenous people call it “la minga.” Why don't we recognize this as a form of energy? The energies of new relationships have a lot to do with the idea of permaculture, of how to inhabit the Earth, and above all how to heal it and how to self-manage health. A lot of people get caught up in the technology, but that’s not my way of thinking.

We have been working hard in recent years, together with other organizations. We convened the Virtual Exhibition of Community Experiences for a Just Energy Transition. More than 120 experiences have been registered from different parts of Latin America. Also, last year we had the Community Energy Encounter, where we invited all communities with experiences in community energy to participate in an exchange and advocacy space in Bogotá. Let’s tell the government that we may be small, but we are not few.

PR: The government has another idea, which they call “energy communities.” How do these two concepts—community energy and the government’s energy communities—overlap or not?

JPSV: I think we have big differences with the government’s proposal for a just energy transition, but we haven’t distanced ourselves because of it. On the contrary, we have sought to come closer. [President] Gustavo Petro did not talk about energy transition five years ago, nor did he talk about a just energy transition.

In 2017, we held a meeting with MAR [Movement of People Affected by Dams]. We said, “If we don’t get involved, the energy transition is going to dispossess us of our territories.” At that time, the wind farms in Mexico, in Oaxaca, and the Jepírachi wind farm here in northern Colombia were starting. We preferred to talk about the climate crisis, instead of climate change, in order to broaden the conversation rather than limiting it. At that time, we took several actions. The Ríos Vivos Movement held the second National Encuentro in Barrancabermeja, with the theme Just Energy Transition. We took the current president of the Chamber of Deputies [representative Andrés David Calle Aguas] to a public hearing so that we could talk about it.

We have opened up to the government because the government started to adopt this within its discussions, but from our perspective it was a discussion that did not reach the executive in a well-developed way, but as a superficial slogan. They started to call for binding dialogues.

This is how the National Development Plan was built. We wrote a proposal that we put on the table, since it is going to be binding. It is called “Promotion and Strengthening of Energies Community,” and it’s the work of many hands. But at various times I have told the government that it was a misleading public policy, and I said to them, what about our proposal? The first year was exhausting, because there were officials who promised us heaven and Earth, and in the end there was nothing.

Another thing we did was to go from ministry to ministry, to disseminate our proposal. A proposal came out within the Ministry of Mines and Energy, and it was a typology, with one of the categories to be called community energy.

To us, that sounded very good, and we said, “They are understanding our proposal.” However, when the first draft of the decree was published, the typology had not been included. An important turnaround to all this came with the change of the head of the Ministry of Mines and Energy. Since Minister Andrés Camacho arrived, I believe that he has listened more to the communities. We designed some spaces for dialogue with the ministry that have been cordial. We signed a memorandum of understanding with the ministry for the promotion of community energy in Colombia.

Those of us who have been building community energy have been doing this work for 40, 30, some 20 years, but it is not just a fad. We emerged [as a movement] because we had the important understanding that the energy model had to be transformed. Community energy began to build the path of how self-management at a local and decentralized level could meet people’s needs, but even more to transform relationships in the territories. This arises from a social process, and those who propose and carry the initiatives out are the communities. The School of Technicians plays an important role, as it seeks to enable people to design, assemble, operate, and repair.

If we achieve these four things [which are part of community energy], we achieve decentralization and not dependence. This is done through community organization that really resides in the territories. That is the fundamental success of an energy community. But if it is promoted as a business opportunity, it is already lined up for failure.

Today, we see a Ministry of Mines and Energy, and perhaps Ministry of the Environment, that is more receptive to understanding other ways of doing things. However, from the point of view of community energy, there has been a very big challenge, and that is that the ministries are distancing themselves from this discussion. There is also the challenge that tomorrow the government and the minister may change, and the dialogue will no longer function. If we do not get involved in the energy communities, there will be no way of getting into what is otherwise a black capsule where we cannot see what is inside.

PR: Thinking about those challenges at the local and national level, what would need to change at the global level for community energy to be better understood and more widely applied?

JPSV: I think the issue is one of cultural transformation. When we reflect on the values that we have as a society today, we will find that they are values that promote capitalism in some way, such as the very issue of competition.

I think that community energy is not the solution to the climate crisis, but it is a door, or a path that we are opening in a world with false solutions. They are small-scale solutions, but as I said, we are small. But if we are many, the change will be more significant.

For example, there is a process in Santander where women used to spend four hours watering their reforestation nursery. With solar pumping, those four hours were taken care of, and now they can dedicate that time to think about themselves or the organization. That is community energy! In any culture or country, it can be done.

Translated from Spanish by NACLA.

Patricia Rodríguez works as International OGI (Optical Gas Imaging) Analyst and Advocate at Earthworks. OGI is an infrared technology that detects fugitive and poorly combusted emissions of methane and volatile organic compounds from the gas and oil industry.