Right after Bayardo [Dr. Bayardo Gonzalez of Matagalpa, Nicaragua] and I were married in 1967, my father had told us, “When ‘comes the revolution,’ you send us the kids!” Now, at that time, the Somoza family looked well-entrenched in power with no revolution in sight and we certainly had no kids. But, of course, the revolution did come and we did send the kids.

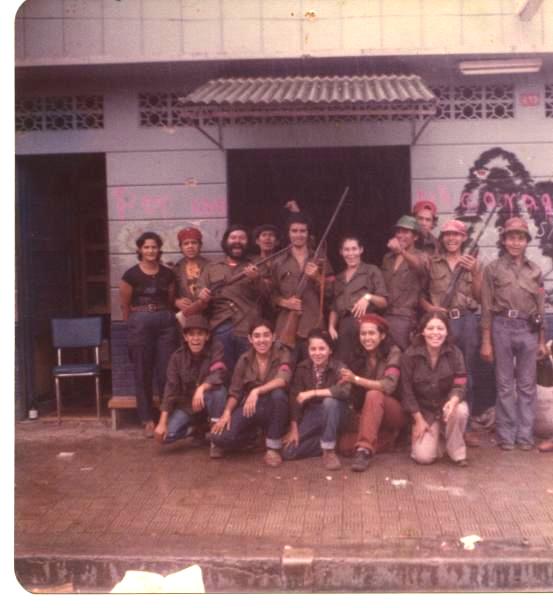

The Sandinistas who were headquartered at Hoyt’s house. Taken in front of Aunt Irma’s store next door. All photos: Katherine Hoyt |

We kept their Pan American tickets ready and their passports with exit visas stamped in them. We listened to “Radio Sandino” every night at 11:00p.m. for the announcement of the “final general strike.” We also received instructions on how to build air raid shelters and what supplies to have on hand.

By now the three FSLN tendencies, into which the Front had divided beginning in 1975, had reunited and, as Humberto Ortega later said, three other very important factors were present which made possible the victory:

1) The people were prepared and ready for a massive popular uprising;

2) The private sector was completely fed up with Somoza and was ready to support another general strike; and most importantly

3) The FSLN, in a culmination of its eighteen years of struggle, was politically and militarily ready to lead the offensive.

On Mother’s Day, May 30, 1979, the announcement came: the final general strike would start June 4th. The next morning I called Pan American Airlines and made the earliest reservations that I could: June 4th. My father would fly down to Los Angeles to pick up the children and fly with them to Seattle. Victoria was ten, and the twins were six. Victoria was a little mother to her brother and sister. Only years later did the children tell me how traumatic they found being separated from both of us and how they worried about being left orphans.

After we watched the children’s plane take off, Bayardo and I put our emergency bags over our shoulders and walked out to the highway. We wanted to spend the final offensive in Matagalpa but with no public transportation operating, we knew we might have to stay in Managua. We were lucky: a private car stopped and gave us a ride all the way home. On that first day of the strike all stores, businesses and doctors’ offices were closed, but it was quiet so we visited friends and relatives. On June 5, however, at 5:00 p.m., Sandinistas entered the city from the east and fighting began. Bayardo had gone out to visit friends. When he called, I said he should stay where he was and not try to get home. I have always believed that, if the children had still been with me, he would have tried to make it home and might have died on that first day.

The next day I crossed the street to stay with Elbia Bravo who intended to remain in the city in her home behind her store. She had told us that we were welcome to stay with her and since I was alone, it seemed a good idea. We were four women: Dona Elbia, her mother Dona Licha, the young maid Angela, and I. By June 7, we could hear what sounded like snipers on our roofs but didn’t know what side they were on. For the first time a jet plane flew over the city strafing the houses. When it was far away, the noise was bum, bum, bum, bum, and then an echo bum, bum, bum, bum. But if it was right on top of you then it was simply BAM, BAM, BAM, BAM. At Elbia’s house, as at our house, we were somewhat protected from strafing and rockets by the platform of the second story. People who lived in one story houses with tile or tin roofs either had already made some kind of air raid shelter or quickly made one in these first days of the fighting. We ate, read and slept.

On Friday afternoon, June 8, Elbia’s house received its first hit by a mortar shell against one of the back bedrooms. The room filled with glass shrapnel from the windows. We were all in the living room at the time and no one was hurt. The next day Elbia and I went up to one of the apartments that she rented on her second floor to see where another mortar had hit. It had made a substantial hole in the wall. (Luckily, the tenants had evacuated for farms outside the city.) It was then that we heard the plane overheard and the explosion behind her house at what had to be the fire department. We listened in horror to the screams and then to the sirens as an ambulance took victims to the hospital. We found out later that eight civilians had died and many more were wounded in the attack.

On Sunday, June 10, I crossed the street over to our house to feed the animals. There was fighting on the rooftops and hot lead (literally hot lead) fell into the kitchen. I crouched under the kitchen table until the fire fight ended. Later, Sandinista fighters told me that there were members of the National Guard on the roofs and that I had been putting my life in danger by crossing the street to feed our dog and cat. There were hard fought battles that week in Matagalpa to take San Jose Church in the south-central part of town and the old San Jose School building as well as the Social Club. We could tell that the fighting was intense but we couldn’t tell where or, more importantly, who was winning.

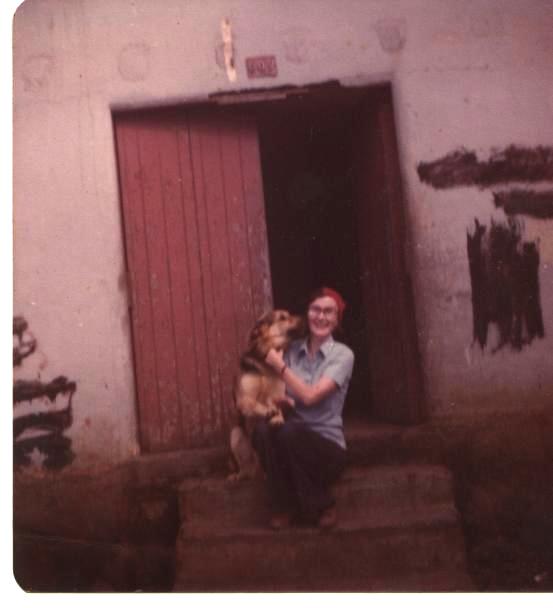

The next day planes flew overhead, strafing and dropping bombs all morning and most of the afternoon. At one point in the afternoon, I had occasion to look across the street at our house. The door was open and our German Shepherd was standing in the doorway looking out. I went over quickly to put him back in, realizing that someone might kill him. Nicaraguans believed that dogs who ate dead human flesh would get rabies and therefore any dog that was running free during battles when there were dead bodies lying out in the open was presumed to be rabid. I was quite certain that our dog had not bitten any dead bodies, but I wanted to get him inside before anybody else decided that he had and shot him. When I went into the house, I saw the reason why the door was open: there were 24 Molotov cocktails made from Flor de Caña rum bottles in two neat rows on the floor of the dining room and several red and black masks on the living room sofa. I said to myself, “They’re here.”

Compañero Maceo, who had taken his nom de guerre from the Cuban independence fighter Antonio Maceo, was the responsable, that is, the one in charge, of the Sandinista brigade. He and another compañero, or compa as they called themselves, had supper with us that evening. At one point, Maceo said to me, “We’ll be using your house. You’ll have to pardon the mess.” Thus began our relationship with an outstanding group of young people who lived in our house for two months. They were Terceristas, members of the Third or Insurrectional Tendency that had been formed by Daniel and Humberto Ortega and others. The Terceristas believed that a broad multi-class coalition of the Nicaraguan people could be brought together under the leadership of the FSLN and could overthrow the dictatorship. The three tendencies within the FSLN had reunited only a few weeks before the final offensive so each still retained a separate command structure for its troops. Our nephew Jose (about whose whereabouts I still knew nothing at this time) turned out to be the responsable of the fighters of the Prolonged Popular Warfare tendency. His command post was on the other side of the block. Our block was strategic for the Sandinistas as they moved house by house toward the command post of the National Guard on the park next to the Cathedral.

The short-wave radio was our life-line. It was how we learned what was going on in the rest of Nicaragua. Radio Netherlands had the best news, followed by Radio Exterior de España. We also listened to the BBC, Radio Moscow, Radio Havana and the Voice of America. We heard reports that the fighting continued in Managua. Thousands were said to be dead from the bombing of residential neighborhoods. Fleeing North Americans could not get to the airport. The building of La Prensa newspaper was reported to be burning. Somoza was also bombing other opposition business and industrial sites on the North Highway out of Managua.

We were being shelled by mortars from a hill outside the city. Often the shelling came at night. On June 12, the storeroom next to where I was sleeping was hit. The noise was deafening. A ten inch hole was blown out of the wall, the brick turned into an enormous quantity of red dust which covered everything in that and nearby rooms. After that, I lay sleepless in bed next to an exposed outside wall for a long time listening to the whoosh of each mortar as it was launched and counting the seconds until each explosion. The time between launch and explosion averaged 19 seconds.

We began cooking for the compas with food that they brought for us and themselves. Often a young man would sit with us and help us sort the pebbles and twigs out of the beans before we cooked them. Cooking, washing and other tasks were divided equally among men and women fighters when they were in the mountains. It was only when they came among civilians that we civilian women began taking over the cooking. We had time to talk with the compas, also. Maceo had been one of the leaders in the battle of Jinotega and told us about that unsuccessful effort that had not been worth the loss of the great peasant comandante German Pomares. “In Jinotega,” Maceo said, “we couldn’t get even a glass of water. In Matagalpa, we are stuffed with food!”

On their way down from Jinotega to Matagalpa, the compas passed through the tuberculosis sanitarium at Aranjuez. Maceo said that he spent two hours talking with an old man trying to convince him that he shouldn’t try to accompany them in the taking of Matagalpa. He told the story in admiration of the old man’s courage and valor. I heard the story thinking of a young man’s respect and caring for the old and sick. Down the highway from Aranjuez, at the entrance to the Hacienda Selva Negra, that same group of Sandinistas set up an ambush for the National Guard. Many National Guard soldiers were killed and the Sandinistas obtained needed weapons. The tank they destroyed remains on that spot as a monument to the battle.

On the night of the 14th, we women all slept in Elbia’s bedroom because it was a protected interior room. That night the compas broke through the double wall that separated Elbia’s house from the Perla Theater next door that had been held by the National Guard. The expected firefight did not materialize, however. The Guardia had abandoned the building.

I got news of Bayardo from the compas. He was working at a field hospital that the Sandinistas had set up at a Catholic orphanage and school. The first hospital that the doctors had tried to set up in a private clinic had been bombed and had to be abandoned. The orphanage was a better building. The doctors and the wounded would be safer there, I thought. But the Sandinistas monitored National Guard radio communications and heard orders being given to pilots to bomb the hospital. According to rumor, one pilot refused and deserted, taking his plane. Bayardo, a long-standing enemy of the National Guard, heard that orders to bomb our house had been picked up as well.

Short-wave radio news reports told us that on June 16, the FSLN took the National Guard post in Leon. The U.S. was urging no arms aid to either side in Nicaragua. On the 17th, we heard the news that the FSLN had called five people to form a provisional government. They were Daniel Ortega, Sergio Ramirez, Violeta de Chamorro, Moises Hassan and Alfonso Robelo.

Occasionally Bayardo could get away from the hospital to spend an evening with me. One morning we were still eating breakfast when the bombing began. First the Perla Theater next door was hit. The compas came rushing into Elbia’s house through the hole in the wall. Then, seconds later, we were hit. We all headed for the door. I was the first to cross the street to our house with our dog on his leash followed by the other women and then the men. As I crossed, I looked back and saw Elbia’s second story and the supermarket next door on the south side totally engulfed in flames. The compas had been debating whether to distribute all the food in the supermarket or to leave it there for use as needed. Now it was gone. We could hear cans exploding from the heat inside the store. The bomb had been an incendiary device of some kind, possibly napalm.

It was on this day (June 20) that ABC newsman Bill Stewart was killed by the Guardia in Managua. One of his fellow journalists filmed his vicious murder and it was broadcast around the world, increasing awareness of the brutality of the Somoza dictatorship. We saw it on television later in Managua. Stewart was lying face down on the ground; the National Guard soldier shot him, kicked him in the head, and shot him again.

Elbia, her mother and Angela, the maid, went to stay at the house of Dona Tanita, around the corner. Dona Tanita had a large house full of refugees. Cooking, cleaning and taking care of children were all perfectly organized in her house, as was each person’s air raid shelter spot. Dona Tanita was one of two women that I knew who performed admirably under the stress of the insurrection, organizing people and tasks, but who broke down afterwards. It is remarkable how the human spirit can hold firm as long as is necessary but then demands relief and rest when the crisis is over.

I went to stay in one of the basement modules of the still-unfinished Catalina Shopping Center behind our house (and connected to it by a hole in the wall). There were about 25 civilians from the neighborhood staying there with their mats neatly laid out by family group in two rows on the floor. People would ask me, “Doña Kathy, aren’t you afraid?” And I would answer, “All my fears went on that airplane to the U.S. with my children.” Mothers who were not as lucky as I and could not send their children abroad were terrified. I remember awaking from my pallet one night and seeing Lydia Rivera, wife of one of the neighborhood dentists, sitting bolt upright, her eyes big as saucers, surrounded by her four sleeping children. She was unable to sleep a wink.

It was in this shelter that I was able to make up for a faux pas that I had committed against a compa whose nom de guerre was “Mexicano.” He had asked me if the house where they were staying was my house. I answered that yes, it was my house. He repeated the question several times and I repeated that yes, it was my house. Too late I realized that what he wanted and expected me to say was that it was also their house! However, I had given him a wool blanket and one night, as he was rolling up in it in that basement module (for some reason with the civilians that night), he said, “I have your blanket.” “No,” I said, “It’s your blanket.” Redeemed at last!

At about this time, I compiled a list of the U.S. citizens in the area who I was fairly sure were all right and gave it to the compas who got it out to FSLN representatives in the U . S. so that our families could be notified but also so that we could be quoted as demanding an end to the bombing. My parents had been frantically calling the State Department for word about Bayardo and me. Of course, officials there could tell them nothing. They were happy to receive a phone call from a representative of the FSLN telling them that we were fine and asking them if they could get in touch with the list of the other people. When the State Department next day called to apologize for being unable to provide any information, my mother startled the officer by saying, “Oh, we have received a call from the Sandinistas saying that they are fine!” Others heard items on shortwave radio news with our names demanding an end to the bombing of Matagalpa.

Radio broadcasts reported that the OAS had asked for Somoza’s resignation. The other dictatorships of Central America abstained in the voting and only Paraguay voted with Somoza, who continued bombing Managua.

Some of the Sandinistas were blessed with more than the usual sense of humor. One day I went on a mission with Compa Mexicano to get some dental anesthesia from the office of a neighborhood dentist. Because I knew the city, I could guide him, although as we went through holes in the walls connecting the houses, everything seemed different. (It was very strange to step through a hole into someone’s bedroom and then try to figure out whose house you were in.) At any rate, we accomplished our mission and at one point when we came out onto the sidewalk to cross a street, Mexicano gave me his Galil rifle (rumored to be the first taken from the National Guard in Matagalpa) to hold. He said that we were going to put me up in front of the National Guard Post and say that “the Yanks have come.” When I tried to return the rifle to him he kept moving ahead until I had walked a block carrying the Galil. I was finally able to return it to him. Mexicano was wounded in a battle the next day. He said that it was because he had violated his promise not to bathe until the victory. The smell of the Sandinistas as they came down from the mountains into the city was unforgettable and many of them succumbed and took baths. We were glad when they did.

Every day, except when clouds were low, we were bombed and strafed from the air. On the 27th of June I noted in my diary that we had five aviation attacks: three times planes came with rockets and twice a jet strafed the city with machine gun fire. Our cooking (in one of the houses bordering the shopping center) was often interrupted when a plane came and we had to turn off the stove and rush to shelter. We learned to eat and like “arroz pasmado” or “interrupted rice.” We ate beans and rice, then rice and beans, followed by “gallo pinto” (rice and beans combined) for variety. Every other day we cooked something for the pets, of which there were several.

On the 29th, a helicopter dropped several big 500 pound bombs on the city. These could destroy half a block of solid construction; the air raid shelters we had were no protection against them. On that day also we were depressed by news of a tactical retreat of the Sandinistas from Managua. We barely noticed the word “tactical,” it was the word “retreat” that upset us. This, of course, was the famous “repliegue” which is commemorated each year with an all-night 26 kilometer walk from Managua to Masaya. The Sandinistas moved 8,000 combatants and civilians out of the neighborhoods of Managua where they were being slaughtered to the free city of Masaya. There the civilians could be more easily trained as militia to continue the fight. On June 30, the Sandinistas in Matagalpa finally got more badly-needed weapons and ammunition from a plane-drop outside the city. I had asked one young fighter several days before why they had not advanced any further toward the National Guard Post. “Señora,” he said, “we have no more ammunition!” “What,” I said, “you have 15,000 civilians in this town counting on you, and you are out of ammunition!” My confidence was shattered. Now, with ammunition, land mines, a 50 mm machine gun, and other items, victory seemed possible. Compañero “Dr. Nicolas” insisted that we have a drink of (a neighbor’s) whiskey to celebrate.

My husband Bayardo had been saying that because of the difficulty in bringing the wounded around the Guardia-held center of town, there was a need for a branch hospital in the northern part of the city. When the decision was made to set one up, he was put in charge. He brought the equipment from his and another doctor’s private clinic to a big house in Guanuca neighborhood. There, doctors and nurses took care of wounded and sick from the north side of town and from rural areas nearby.

On the morning of July 2, the Matagalpa National Guard post fell to the Sandinistas. The Guardia still retained a straight line of important buildings from the center of town across the Matagalpa River and out of town: the Cathedral, the Red Cross building, the hospital, the public high school and the hill beyond. That day, I went to see the grenade hole in the ceiling of our bedroom exactly over our bed. The bed had, luckily, been stood up on its side to serve as a barrier to fire that might come through the window and so was undamaged. When I returned to our module in the shopping center, I found that Compa Martin was evacuating all of us civilians because we were so close to sites that they had heard on Guardia radio were shortly to be bombed with 500 pound bombs. We civilians readied our bags, put leashes on our pets, and got ready to go. There was a grandfather on a stretcher who was to die a few days later and a number of small children. Martin was a model of patience with civilians. He was a bazooka man rumored never to have shot the bazooka. We could always rely on him to get us salt or flour when we needed it. I know his patience was tried that day, however, as he shepherded us out of the danger zone. Bayardo came and got me and we went up to Guanuca. We found a little house near his branch hospital where we could live for the duration. There was no air raid protection at the house but when the planes came I could go to the hospital to sit out the attacks.

Life in Guanuca barrio was different from downtown. With the Sandinistas firmly in control and no fighting on the ground in the neighborhood, the residents were organized into civil defense committees to distribute food in an organized fashion based on ration cards. About once a week, someone would go out into the countryside, slaughter a steer and bring meat back to town. On Tuesday and Saturday mornings, food was passed out to all residents. Beans, corn, and rice were given out and then alternately coffee beans, sugar, salt, cheese, or green bananas (for cooking). Milk was for children under two. Bread and vegetables were rare.

Hoyt in front of the little house in Guanuca Barrio with the family’s German Shepherd. |

A woman named Dona Victoria had been cooking for Bayardo and some of the compas. So, I added my food ration card to theirs and ate at her house as well. She took the corn, ground it, and made delicious tortillas which we ate with boiled beans and sweetened coffee three times a day. I can still taste how delicious her food was. But, of course at the time, while we greatly appreciated her efforts, we would dream of fruit, bread, vegetables and chocolate. People who had backyard gardens gave their produce away. When we went out we might pick up a few lemons or chayas (small squash).

I worked on compiling “revolutionary thoughts” taken from works in our library by Sandino, Che Guevara and Padre Camilo Torres, who died fighting with the Colombian guerrillas in the 1960’s. These were used to fill odd moments on Radio Insurrección, which was the first station captured by the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. The neighbors across the street (whose daughter had been an English student of mine) loaned me a typewriter so that I could type the notes. Since there was limited access to news for Radio Insurrección to broadcast, the quotes were used fairly frequently.

On July 9, we heard on the short wave radio that there were U.S. personnel and military aircraft in Costa Rica near the border with Nicaragua and that the U.S. government was pressuring for a broadening of the base of the provisional government (the Junta) that had just been named. I noted in my diary that people were “disgusted.” With the inclusion of both millionaire businessman Alfonso Robelo and Pedro Joaquin Chamorro’s widow Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, the Junta certainly appeared to be broad enough. It was obvious that the U.S. did not want a majority of the five members to be Sandinista sympathizers, a ridiculous demand considering the fact that the Sandinistas were leading the struggle and providing the cannon fodder!

Also on July 9, the 25 members of the National Guard who had been holed up in the Matagalpa Cathedral surrendered. Radio Insurrección broadcast live the coaxing of the men out of the church by Bishop Julian Barni and by a soldier who had slipped out earlier. Obviously most convincing to the Guardias were the words spoken in pure peasant accent by their fellow soldier who told them: “Brothers, they are treating me well; I’ve eaten; yes, I’ve eaten beans and cheese!” The soldiers, who had survived a week on toothpaste and a bottle of whiskey, came out one by one. But the National Guard still held the Red Cross building, the hospital, the public high school and the hill behind the school from which they continued to shoot with a 50mm machine gun into the city causing numerous wounded.

We heard on the short wave that the U.S. aircraft left Costa Rica and that Somoza dropped several bombs inside Costa Rican territory. The provisional government presented a solution to the conflict in which it promised to respect the lives of the members of the National Guard. Somoza, however, rejected the proposal. The United States pressured for the addition of two conservative members to the five constituting the provisional government. The Sandinistas held firm in their refusal.

On Sunday, July 15, Bayardo and I went downtown to our house. We could get downtown most days by following a route that took us across dangerous streets only at places where the compas had set up barricades of sandbags. They would tell me, “Señora, bend over and run!” I would always answer “I can bend over and I can run but I can’t do them at the same time!” They would laugh at the tall skinny gringa and I would do my best. At our house we got the local news from the compas. Five days previously, Martin had taken over the command of our house and had gotten his troops to clean. I was delighted, but within a few days, the house was filthy again!

While we were there, three airplanes and a helicopter flew over the city. One of the planes strafed us with machine gun fire and the helicopter dropped three 500 pound bombs on residential blocks in different parts of town. Bayardo and I stood in the front hall of our house and peeked out the door to watch the helicopter circle the sky. The pilots flew high now that the Sandinistas had their own 55 mm machine gun which could bring down a low-flying copter. This meant that the bombing was even more random than before. A man was blown to bits in his house by one of the bombs that landed in Guanuca (the neighborhood where we were staying). His family had to gather the parts of his body from all over the wreckage of the house to bury in the yard in a plastic bag. All the dead whose bodies could be recovered were buried in back yards as there was no access to the cemetery. Afterward, what made us so angry about this particular bombing was that it was so close to Somoza’s departure. He was leaving anyway, we thought, so why did this man (and any others who were killed that day that we didn’t know about) have to die?

Before we headed back to our little house near the hospital in Guanuca, we got some essentials from the compas such as candles, matches and toilet paper. I wrote in my diary that before we went to bed that night, “a neighbor lady knocked on our door to tell us that she had heard a newsflash that Somoza was leaving! We had good dreams!”

On Tuesday, July 17, at 5: 30 am we were awakened by the bells of Cathedral and shooting in the air. Somoza had departed during the night for safe haven in the United States. The provisional government scheduled its departure from San Jose, Costa Rica, for 3:00 pm but then cancelled the flight because Francisco Urcuyo, who had been Somoza’s Vice-President and who had been left as the interim president, wouldn’t guarantee their safety. He said that he would stay in power until 1981!

We went downtown to our house. Maceo and many of the compas were getting ready to leave Matagalpa, evidently to take Boaco. They had new uniforms and some new arms. I remember that they gave me a brand new grenade launcher to hold. Martin and Candida, a nurse, would remain in charge of our house.

On the 18th, the morning news said that the provisional government had arrived in Leon. The news at noon added that the United States had withdrawn its ambassador and was threatening to declare Somoza persona non grata in the U, S. if Urcuyo did not turn over the government to the new Junta. National Guard members were surrendering all over the country. Most of the Air Force was reported to have left in its planes for Honduras and Costa Rica. The evening news finally reported that Urcuyo had left Nicaragua.

Dr. Gonzalez in front of destroyed buildings around Matagalpa’s central plaza. |

My diary entry for the 19th of July states: “This really was the day of victory! At noon, Bayardo and I headed downtown taking pictures of [niece] Lucila and her militia, the ruins of the area around the Guardia post and of the compas at our house. We had a couple of drinks with the compas and neighbors [from a bottle of gin that had inexplicably survived in the back of one of our kitchen cupboards]. The compas sang an FSLN anthem [the one that would become the song of the Army] and Martin gave a little speech. We went to the Sandinista hospital and the FSLN Central Command and then to visit friends.”

This was the first time we had walked many of Matagalpa’s streets since the beginning of June. There was a great deal of devastation in the center of town where buildings had been bombed by the Guardia or burned by the Sandinistas. The smell of rotting corpses was still in the air. Everyone was tired but happy. Rebuilding looked like an enormous task but people seemed ready to begin.

This chronicle was originally published on NicaNet, the Nicaragua Network, a project of the Alliance for Global Justice.