At the recently concluded four-day “show” of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI), many new, largely war-related, technologies were on display. Among them is something called VADER, produced by Northrop Grumman, one of the world’s largest weapons manufacturers and a self-proclaimed “leader in global security.” One of the customers for this technology, it was reported at AUVSI 2011, is the Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection Agency (CBP).

VADER stands for Vehicle and Dismount Exploitation Radar. According to Wired magazine’s “Danger Room” blog, VADER was first developed for use by the U.S. military in Afghanistan to spot individuals at a great distance and track them. As is often the case with such technologies, the radar system has come “home” to fight “wars” of various sorts.

CBP had prohibited Northrop Grumman from revealing the very fact that the DHS agency was using VADER—according to a company spokesperson with whom I spoke. So she was surprised when she read in Unmanned Daily News, the show’s newspaper, that a CBP representative had discussed it with reporters at the huge gathering. As reported by the article, CBP “is pleased with the radar's performance in operations so far.” The Northrop Grumman spokesperson recounted her conversations with CBP officials: “They say VADER is a game-changer,” she effused.

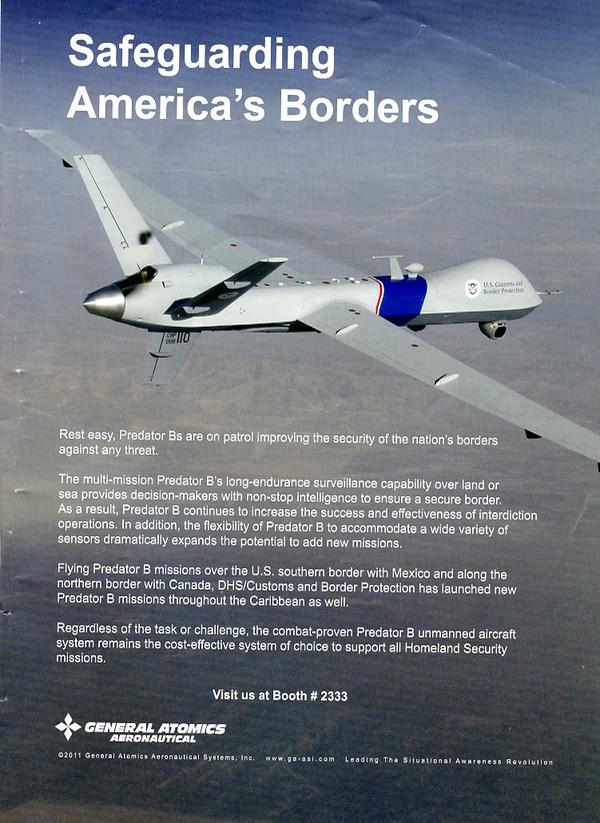

VADER’s advantages include the fact that it is an all-weather technology. It can thus see through dust storms and atmospheric haze. Deployed on CBP’s small, but growing fleet of Predator drones (see General Atomics's advertisement for border drones below), VADER can also reportedly distinguish between people and animals—and it can do so from an altitude of 25,000 feet.

VADER is part and parcel of the growing electronic surveillance infrastructure in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. In early 2011, DHS announced that it had cancelled its previously-much-touted SBInet, a multiyear, multibillion-dollar integrated system to deploy the “most effective proven technology, infrastructure, staffing, and response platforms and integrate them into a single comprehensive border security suite for the department.”

Yet the goal of having electronic eyes throughout the borderlands remains. Only now the recipe is one that embraces a greater mix of tools, ones tailored to the terrain of specific locales. This relatively decentralized approach relies increasingly on what are called “mobile surveillance units” (each one with a price tag of approximately $800,000)—in addition to stationary towers with optical and infrared scopes and VADER-equipped drones.

Yet the goal of having electronic eyes throughout the borderlands remains. Only now the recipe is one that embraces a greater mix of tools, ones tailored to the terrain of specific locales. This relatively decentralized approach relies increasingly on what are called “mobile surveillance units” (each one with a price tag of approximately $800,000)—in addition to stationary towers with optical and infrared scopes and VADER-equipped drones.

As anthropologist Josiah Heyman has asserted and explored, the “wall” along the U.S.-Mexico divide is both physical and virtual—and increasingly so it seems.