On New Year’s Day of 1994, the day the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) seized four towns in the southern state of Chiapas and declared them to be liberated not only from the rule of the Mexican state, but from the global economy as well. The EZLN rebellion was a reaction to the severe poverty and state-sponsored violence long suffered by Mexico’s indigenous communities—state violence that increased ten-fold in the wake of the uprising, as police, soldiers, and civilian paramilitaries engaged in a vicious crackdown on communities thought to be under Zapatista influence.

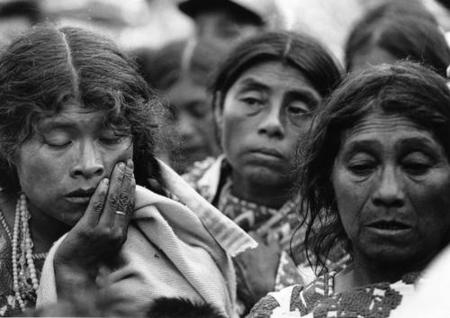

This past September 19, in a federal civil c ourt in Hartford, Connecticut, former Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo—now a resident of Connecticut and an economics professor at Yale—was charged with crimes against humanity for the 1997 killing of 45 unarmed members of the Tzotzil Maya ethnic group, in the Chiapas village of Acteal. Ten survivors of the massacre filed the charges under a U.S. law that permits foreign citizens to seek compensation from former foreign functionaries guilty of various kinds of abuse, now residing in the United States. Zedillo was president of Mexico from 1994 through 2000. After a 1998 investigation, Amnesty International reported that "compelling evidence shows that the authorities facilitated the arming of paramilitaries who carried out the killings and failed to intervene as the savage attack continued for hours."

ourt in Hartford, Connecticut, former Mexican president Ernesto Zedillo—now a resident of Connecticut and an economics professor at Yale—was charged with crimes against humanity for the 1997 killing of 45 unarmed members of the Tzotzil Maya ethnic group, in the Chiapas village of Acteal. Ten survivors of the massacre filed the charges under a U.S. law that permits foreign citizens to seek compensation from former foreign functionaries guilty of various kinds of abuse, now residing in the United States. Zedillo was president of Mexico from 1994 through 2000. After a 1998 investigation, Amnesty International reported that "compelling evidence shows that the authorities facilitated the arming of paramilitaries who carried out the killings and failed to intervene as the savage attack continued for hours."

While narco violence continues to overshadow state violence in Mexico, mostly for its deliberately garish brutality, state violence is never far from view—especially in rural areas. The lawsuit reminds us of that sad fact of life. It also reminds us that resistance, on many fronts, is possible.

Last week, Zedillo appeared in court and claimed that, as a former president of a sovereign country, he was immune from judgment. He also argued that he was not responsible for the killings. The plaintiffs, however, argued that Zedillo refused to enter into a serious dialogue with the insurgents and instead opted for a violent response to the uprising, targeting not only armed guerrillas, but also their nonviolent indigenous supporters. The plaintiffs also argued that the president conspired with local and state officials to hide his role in the crackdown. They are seeking $50 million in damages.

However, not all the victims’ supporters are happy with the suit. Some see it as an attempt to receive blood money, rather than justice. Bishop Raúl Vera López, a long-time supporter of Chiapas’s indigenous communities, told the daily paper La Jornada, that while the former president may well be guilty of crimes against humanity, the plaintiffs don’t represent the majority of those affected by the Acteal massacre, but rather a small group that had split off from the self-governed community. The majority, he said, “do not agree with a civil demand. Some of them have told me they don’t agree because ‘they are negotiating with the blood of our dead, and what we want is that the crime not be repeated. We want to find the guilty, and to judge them, but so that this crime cannot be repeated.’ ”

For more from Fred Rosen's blog, "Mexico, Bewildered and Contested," visit nacla.org/blog/mexico-bewildered-contested.