In a July 29th speech at a fundraiser in Jerusalem, presidential candidate Mitt Romney attributed the stark difference in economic development between Israel and Palestine partly to cultural factors. To illustrate his case, he provided incorrect data showing that Israel’s per capita gross domestic product was twice that of Palestine (the difference is actually around 20 to 1). In any case, it was but one indicator that allowed Romney to “recognize the power” of “culture, and a few other things” in determining “economic vitality.” One of “a few other things” that has influenced Palestine’s economy, unmentioned by Romney, is Israel’s crippling, U.S.-funded military occupation of Palestine, now in its 45th year, which has dispossessed the Palestinians of land, water, and sovereignty.

Romney’s comments elicited a response from Jared Diamond, a professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles, who protested the fact that Romney had invoked Diamond’s work in his Jerusalem speech. Diamond’s August 1 New York Times op-ed, “Romney Hasn’t Done His Homework,” condemned the candidate for misrepresenting the findings of his book, Guns, Germs and Steel.

Curiously though, Diamond’s op-ed didn’t refer to Romney’s most basic error: omitting the role of the Israeli occupation in Palestine’s underdevelopment. That’s likely because Diamond, in criticizing Romney, seems oblivious to the role of outside interference himself. Instead, Diamond’s op-ed effectively endorses a focus on oppressed peoples’ supposed cultural defects as an explanation for their lack of development:

Just as a happy marriage depends on many different factors, so do national wealth and power. That is not to deny culture’s significance. Some countries have political institutions and cultural practices—honest government, rule of law, opportunities to accumulate money—that reward hard work. Others don’t. Familiar examples are the contrasts between neighboring countries sharing similar environments but with very different institutions. (Think of South Korea versus North Korea, or Haiti versus the Dominican Republic.)

Whereas Diamond simply disregards Israel’s economic strangulation of Palestine, in the case of Haiti, Diamond adds a gratuitous dose of blame, suggesting that Haiti’s centuries of misery are due in part to a failure to “reward hard work.” He also places his casual insult within parentheses, demonstrating how self-evident he believes his prejudiced claim is. But given the number of foreign-imposed traumas that Haiti has confronted, when does an offhand slur like Diamond’s cross the line from merely ignorant to obscene?

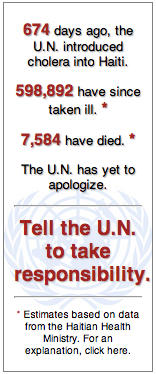

Before turning to the history of colonial sabotage of Haiti, which reached a level of savagery unmatched in the Dominican Republic or anywhere else in the hemisphere, it’s worth considering Diamond’s comments in light of Haiti’s present state of affairs. Diamond has the gall to bring up Haiti’s internal deficiencies as thousands of United Nations troops have continuously (and unjustifiably) occupied Haiti for eight years on the heels of a 2004 U.S.-backed overthrow of the constitutional government of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Almost two years ago, in an act of criminal negligence, UN soldiers introduced cholera into the country, which has so far killed at least 7,500 and sickened 600,000. The UN has yet to apologize or provide reparations to its victims, even as its budget for military activities dwarfs its own funding to treat the disease. The UN troops’ impact on Haiti becomes even clearer when one considers their record of rape and abuse of Haitian children, and their repeated killings of Haitian civilians. (Historian Greg Grandin and I ran through a more comprehensive list of the UN troops’ malfeasance last year in The Nation.) Needless to say, Professor Diamond doesn’t explain how improving Haitian cultural shortcomings will spur economic development in a country that has registered 377 new cholera deaths and nearly 45,000 cases of the illness in the past three months alone.

This is not the first instance in which The New York Times has allowed for space in its opinion pages to disparage a society long victimized by world powers. In 2010, the Times’ resident pundit David Brooks took advantage of Haiti’s January 12 earthquake to assemble a number of bigoted tropes for his January 14 op-ed, as untold thousands lay dead in Port-au-Prince:

[Haiti] suffers from a complex web of progress-resistant cultural influences. There is the influence of the voodoo religion, which spreads the message that life is capricious and planning futile. There are high levels of social mistrust. Responsibility is often not internalized. Child-rearing practices often involve neglect in the early years and harsh retribution when kids hit 9 or 10. We’re all supposed to politely respect each other’s cultures. But some cultures are more progress-resistant than others, and a horrible tragedy was just exacerbated by one of them.

Although Diamond avoids Brooks’ cruder formulations, his op-ed reflects the same blame-the-victim approach to analyzing Haiti’s underdevelopment. This commonality is unsurprising, given that Diamond’s previous scholarship on Haiti suffers from much the same failing.

In his 2005 book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, Diamond argues that the different outcomes between Haiti and the Dominican Republic “become even more striking when one reflects that Haiti used to be much richer and more powerful than its neighbor.” Incredibly, in a chapter dedicated to the different historical trajectories of the two economies, Diamond completely omits France’s relentless immiseration of its former colony, which emancipated itself in history’s only successful slave rebellion. France coerced the new state of Haiti into paying a post-independence indemnity for “lost property”—i.e., slaves. In 1825, facing the threat of 14 French gunships stationed on its coast, Haiti agreed to pay a sum about the size of France’s yearly budget at the time in exchange for normalized relations. By 1900, Haiti was dedicating 80% of its national budget to such payments, and did not hand over its final installment to France until 1947 (in total, Haiti paid France about $21 billion in today’s U.S. dollars). The long-term impact of over 120 years of this illegitimate debt payment on Haiti’s development could not be overstated—and yet in Diamond's examination, it’s nonexistent.

Diamond also scrubs longstanding U.S. support for Haiti’s corrupt Duvalier dictatorships from his narrative. This U.S. backing, combined with international legal privileges to sell the country’s resources and enjoy access to international financing in the name of Haiti’s people, further consolidated the Duvaliers’ three-decade grip on the society until 1986.

Even Diamond’s scant praise for Haiti is an opportunity for clarification. Although Diamond lauds “Haiti's remarkable achievement in abolishing its army” in 1995, he fails to mention that the policy’s architect, President Aristide, was overthrown—not just once, but twice. The first coup took place in 1991, organized by military and paramilitary leaders who received money from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. During Aristide’s second administration, the United States played a key role in fomenting a destabilization process that concluded with Aristide and his family being whisked away to the Central African Republic aboard a U.S. plane. (A longtime U.S. Congressman has even been quoted admitting that Washington overthrew Aristide for abolishing the Haitian army.)

UN Deputy Special Envoy Paul Farmer provided further background to this second overthrow in his 2010 Congressional testimony:

Beginning in 2000, the U.S. administration sought, often quietly, to block bilateral and multilateral aid to Haiti, having an objection to the policies and views of the administration of Jean-Bertrand Aristide, elected by over 90% of the vote at about the same time a new U.S. president was chosen in a far more contested election. How much influence we had on other players is unclear, but it seems that there was a great deal of it with certain international financial agencies, with France and Canada; our own aid, certainly, went directly to NGOs, and not to the government. Public health and public education faltered, as did other services of special importance to the poor. … Choking off assistance for development and for the provision of basic services also choked off oxygen to the government, which was the intention all along: to dislodge the Aristide administration.

Diamond is apparently unaware of any of this. In Collapse, he instead makes the decontextualized criticism—one year after Aristide’s second overthrow, when the forces of an unelected replacement government were killing thousands—that Haiti’s “perennially corrupt government offers minimal public services.” To Diamond, evidently, a concerted effort by the United States of “choking off” assistance for Haiti’s basic public services to “dislodge” an elected leader is irrelevant.

Although Diamond’s Collapse does contain some valuable information, like the varying ecological strains that affect Haiti and the Dominican Republic, his repeated exclusion of foreign intervention makes even his final conclusions laughable. In the lead-up to the 2004 coup in Haiti, the Dominican Republic served as a base for U.S.-trained death squad leaders, who launched incursions into Central Haiti, terrorizing and killing civilians. In the face of this interference, however, Diamond argues that the Dominican Republic should eschew an imagined isolationism: “For the Republic not to be involved with Haiti,” he writes, would be “unthinkable.” Ironically, he pushes for the Dominican Republic to “assume a larger role as a bridge, in ways to be explored, between the outside world and Haiti.” In short, Diamond’s recommendations betray the naïveté of someone who, like Romney, has not done his homework.

*

Diamond and David Brooks show the ease with which members of the U.S. intelligentsia can attribute Haiti’s failure to develop to its inherent inferiorities—within the pages of the paper of record, no less. Never mind that Haiti’s political institutions have been deeply shaped by the U.S. occupation of 1915-34; or that its attempts at honest government were regularly subverted by the U.S., France, and Canada; or that those three countries scorned the rule of law when they manipulated the results of the U.S.-financed sham elections of 2010. In light of such facts, Diamond’s argument in The New York Times that there’s a scarcity of cultural and political virtues in Haiti is actually more a reflection of the debased norms of the intellectual class in the United States.

As over a hundred Haitians literally defecate to death each month, succumbing to an epidemic caused by a foreign occupation force, it’s worth asking of Jared Diamond the same question he posed to Mitt Romney: Will he continue to espouse one-factor explanations for multicausal problems and fail to understand history and the modern world?

Take Action:

For readers interested in demanding basic accountability from the United Nations, I strongly encourage visiting www.UNdeny.org, where you can watch the award-winning short film, “Baseball in the Time of Cholera,” and sign up for updates regarding the work of the Institute for Justice Democracy in Haiti. IJDH aims to compel the UN, through a legal suit it filed nine months ago on behalf of 5,000 affected Haitians, to “install a national water and sanitation system that will control the epidemic; compensate for individual victims of cholera for their losses; and issue a public apology from the United Nations for its wrongful acts.” The UN has yet to respond.

Also, over 1,600 people have signed this petition to the UN, created by the group Just Foreign Policy, which is also responsible for the regularly updated Haiti Cholera Counter.

It is particularly important that U.S. citizens participate in these kinds of campaigns. Journalist Jonathan Katz, who first broke the story of the UN troops’ negligent disposal of cholera-contaminated sewage, notes that the “U.S. paid 27% of last year’s U.N. peacekeeping budget, which in [Haiti’s] case meant that U.S. taxpayers provided $215 million of a $793 million operation . . . A major reason the U.N. peacekeeping mission is in Haiti is that the State Department and Pentagon want it to be there—it’s a far cheaper option than keeping U.S. troops stationed in Haiti full-time, for instance.”

Keane Bhatt is an activist in Washington, D.C. He has worked in the United States and Latin America on a variety of campaigns related to community development and social justice. His analyses and opinions have appeared in a range of outlets, including NPR, The Nation, The St. Petersburg Times, CNN En Español, Truthout, and Upside Down World. He is the author of the new NACLA blog “Manufacturing Contempt,” which takes a critical look at the U.S. press and its portrayal of the hemisphere.