It’s a steamy, overcast monsoon morning in Nogales, Sonora, just across the border from the United States. I’ve come to learn more about what happens to Mexican deportees, many parents of children, who are left off by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in downtown Nogales at two in the morning. My inquiries take me here, just three blocks south of the Mariposa border truck crossing on the northern end of town. I’m in front of a ramshackle structure that barely passes for a building that has been safe haven for thousands of deported immigrants since the late 1990s.

Rickety stairs at the narrow sidewalk reach up into a dark social hall walled in by hand-painted murals. One panel shows a trimly bearded Jesucristo in a baseball cap and jean jacket presiding over a last breakfast or supper of beans and rice. Another is a Frida Kahlo knockoff—a tall, dark, handsome woman carrying an armful of lilies, her lower half blocked by an almost caricatured monarch butterfly.

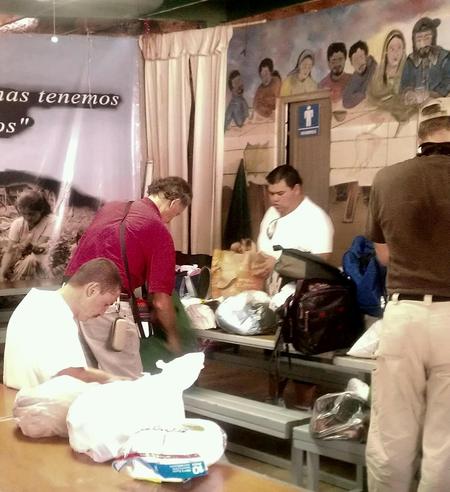

I’m at the Kino Border Initiative’s Aid Center for Deported Migrants (CAMDEP), run by the Jesuit Refugee Service USA and numerous other supporting organizations. Around here, it’s known simply as the comedor (dining hall). This day, nearly 100 deportees, mostly men, some women, sit on benches, many with heads in hands, waiting for the first civilized meal in a nightmarish odyssey starting with their arrest days, weeks, or months before.

Despite record low apprehensions by the Border Patrol in Arizona, the busiest crossing on the U.S.-Mexico border, ICE dragnet operations continue to trap and detain hundreds of thousands of people throughout the country. Many of these deportees are people who have entered the country without inspection more than once. That re-entry charge, a felony crime, translates to incarceration in filthy, overcrowded cells, and lengthy detentions while waiting for hearings. Ultimately, for the majority whose families can’t afford bonds up to $30,000, the charge also means deportation.

Staff member Father Ricardo gets up to briefly bless the disconsolate crowd: “Lord, bless all these travelers, whether they are going to the south or to the north. Give them strength to do what they have to do. We pray for their safety, for their families, and their children, and ask God’s blessing over the food before us today, amen. Any announcements?” The Kino Initiative staff nurse, straw basket of bandages and medicine in hand, announces she is ready to administer first aid for blisters, bites, cuts, and other wounds. Madre Lorena asks for volunteers to fold donated clothing. Dozens raise their hands. A psychologist visiting from Colima, in Central Mexico, conducts a group exercise that gets people, despite themselves, moving their eyes and bodies in different directions.

“It’s a little body movement used to help reduce the effect of the trauma,” she later explains, as we sit on a cement wall at the Grupos Beta headquarters a half mile from CAMDEP. “These people have been out in the desert, some have been in prison or detention, many don’t have a cent to their names. All they have is the moment and in that moment we try to help them look forward, not backward. No, never look backward.”

Grupos Beta, a Mexican federal entity, was started in 1991 as a sort of “humane” Border Patrol. Members, often former employees of branches of Mexican police, assist migrants and deportees to get back to their towns and villages safely. Along the border, Grupos Beta has a hygiene and first aid station, showers, free telephones, and, for many, the connections that will get them back to the towns and villages in Michoacán, Puebla, Zacatecas, and Oaxaca, where their journeys started days or decades earlier.

As we drive up to the agency’s Nogales office, men stand in line to make the long-dreaded phone call to the wife or children left without breadwinners in San Diego, New Orleans, or Phoenix. “Hola mi preciosa. Tu papi tenía que ir, pero pronto regrese, pronto, cuida bien a tu mami” (Hello, my sweetheart, your daddy had to leave but he’ll be back soon, very soon, take care of your mama for me). Miguel, a distraught father of three arrested for unpaid traffic tickets in northern California, turns from the dead phone and says to no one in particular, in accented English: “What will happen to my family? They have no money, they’ll be evicted." Another traveler, Davi, says he thinks his wife filed for divorce now that he is deported, and he will never see his three–year old daughter again. “After I was arrested, the mother moved and took the baby; I don’t know where they are.” When I say I am from the other side, he desperately writes down the last phone number of his ex, and the baby’s name, Graciela. “Graciela, Graciela. Just put an ad in the newspaper and say: father, recently deported, looking for his baby girl, Graciela. And just put your email. What are the chances?” He looks at me with tears of resignation. The therapist slides over closer to him and says, “Maybe you won’t see her again very soon. But when you get back to your town in Oaxaca, there will be many little girls without fathers, and you can comfort them. Some little girl will be glad for your comfort. Don’t give up, look forward.”

Back at the comedor, the last group of morning diners washes dishes and folds clothes for Madre Lorena. A young man, distraught, is frantically rummaging through the hygiene items and bags of clothes. He explains “I need some deodorant, I can’t travel without deodorant.” The fellow tells me he’s from San Salvador, that he no longer has family that knows or cares about him, and he’s heading for Canada. "Where in Canada?" I ask. He doesn’t remember; he lost the phone number. He’s planning to travel on the undercarriages of trains heading north—eight days, it takes only eight days. “Solo ocho días.” Once he gets there, he’ll get political asylum and a job, and all will be well. Something in his manner and his look make me ask if he is Jewish. No, no, but the man who gave me my one chance, back in San Salvador, was Jewish. He said he fled from his country, too, that the government was going to harm him. He got safe haven in El Salvador. “Did he have a number tattooed on his body?” I ask and he looks at me strangely. “Yes, yes he did. On his arm. He died, he was 93. His family, they got separated. I loved that man. Now I got nobody.”

More than 50% of those criminally charged with second and third entries are parents of children. I picture myself as one of those parents. Ostensible crime leading to my deportation: broken headlight. Would I look for a remote canyon and try to cross again, knowing the odds full well? Could I live with myself if I didn’t give it a try?

Laurie Melrood lives in Tucson and is a long-time immigrants rights advocate. See also "Children As Collateral Damage," by Joseph Nevins, November 7, 2011. For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. And now you can follow it on twitter @NACLABorderWars. See also the May/June 2011 NACLA Report, Mexico's Drug Crisis; the Jan/Feb 2009 NACLA Report, Taking on Policy in the Obama Era; and the May/June 2007 NACLA Report, Of Migrants & Minutemen.