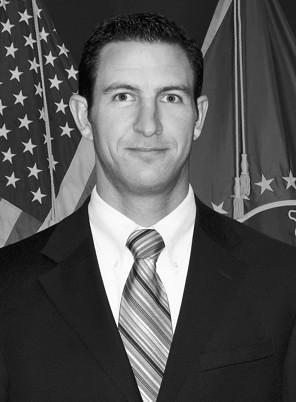

It was in the early hours of October 2 that a ground sensor alarm went off near Naco, Arizona, in an area suspected to be a drug-smuggling corridor. U.S. Border Patrol agents responded, shots were fired, and Agent Nicholas Ivie, 30, was soon dead.

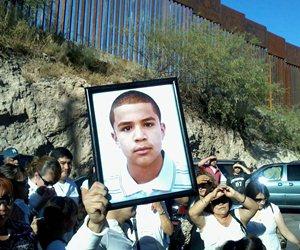

A little more than a week later, late on the night of October 10, Border Patrol agents responded to a report of two alleged narcotics smugglers near the boundary wall that divides Nogales, Arizona from Nogales, Sonora. As in the Naco incident, shots were fired, and someone was killed. In this case, the victim was José Antonio Elena Rodríguez, a 16-year old youth.

In both cases, the killers were Border Patrol agents (unidentified as of this writing). Where they differ is that the first case was a mistake, one involving “friendly fire”; the second incident was not. According to the Border Patrol’s one, brief official statement on the Nogales incident (see below), an agent shot the young man after being assaulted by rocks thrown from the Mexican side of the boundary.

Although the investigation into José Antonio Elena Rodríguez’s death is ongoing on both sides of the international divide, what seems very clear is that the shooting was easily avoidable. That it happened also highlights the urgent need to de-escalate the multifaceted “war” in the borderlands and to demilitarize the region.

Whether or not José Antonio Elena Rodríguez’s was the intended target of the Border Patrol’s hail of bullets—with several hitting him (according to one report, seven struck him in the back) and upwards of 12 striking the building he was beside—is not known. The lawyer representing the Rodriguez family in this case surmises that José Antonio might have simply at the wrong place at the wrong time, that he was on his way to the nearby convenience store where his older brother worked to help him close his shift.

Regardless, it stretches credulity that the young man could have posed a threat to Border Patrol agents. José Antonio Elena Rodríguez was on a street in downtown Nogales that runs along Mexico’s northern boundary when he was shot, at least 50 feet away (in terms of on-the-ground distance) from the agents. Moreover, the agents were 15-20 feet or so above the street, standing on a cliff behind a 20-25-foot-high wall.

Regardless, it stretches credulity that the young man could have posed a threat to Border Patrol agents. José Antonio Elena Rodríguez was on a street in downtown Nogales that runs along Mexico’s northern boundary when he was shot, at least 50 feet away (in terms of on-the-ground distance) from the agents. Moreover, the agents were 15-20 feet or so above the street, standing on a cliff behind a 20-25-foot-high wall.

Because the wall is porous—it is composed of vertical steel bars with gaps of 5-6 inches between them—rocks could have passed through in theory if thrown from a position directly across from the agents. Nonetheless, a combination of desert brush along the lower reaches of the barrier (see the photo), the distance, and the narrowness of the gaps would have made it extremely difficult to succeed at striking the agents. But even if rocks were passing through, the agents, if they felt threatened, could have moved laterally and taken advantage of the protection afforded by the steel bars and the changed angle.

The agent (or agents) who fired upon José Antonio Elena Rodríguez would have had to have been standing right along the wall to shoot between the steel bars. As such, the Border Patrol would not have been threatened by rocks flying over it. Had they been, the agents could have simply retreated as the suspected drug smugglers were long gone, having already scaled the barrier and back in Mexican territory.

That the agents did not evade the alleged threats and, instead, responded with deadly force is indicative of what has become an institutional way of life for the U.S. Border Patrol—and the “homeland security” apparatus in the borderlands more broadly. It is also illustrative of a perv asive worldview among federal authorities that casts the U.S.-Mexico border region as dangerous, and inherently so—as if the alleged dangers had nothing to do with the militarized infrastructure and practices of exclusion implemented by Washington.

asive worldview among federal authorities that casts the U.S.-Mexico border region as dangerous, and inherently so—as if the alleged dangers had nothing to do with the militarized infrastructure and practices of exclusion implemented by Washington.

José Antonio Elena Rodríguez is the second Mexican teenager shot by the U.S. Border Patrol in Nogales, Arizona, in less than two years. In January 2011, an agent fired into Mexico, killing Ramses Barron, 17, also allegedly for throwing rocks. According to the Los Angeles Times, at least 15 individuals—including unarmed and non-resisting migrants in federal custody—have died at the hands of U.S. border authorities since 2010.

Such levels of state violence—and impunity for such—are what typically characterize war zones and territories under occupation. In this regard, it is hardly a coincidence that occupied Palestine is also a place where alleged rock throwers are sometimes fired upon—in this case by the Israeli military—and killed.

Both Nicholas Ivie and José Antonio Elena Rodríguez died in the effort to stymie drug smuggling, as part of the “war on drugs,” one component of the multifaceted conflict waged by Washington in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Their deaths and the shootings that caused them are tragic reminders that the “war” is actually not against narcotics, so much as it is against people—those actually involved in the illicit drug trade, those imagined to be, and those who just happen to be in the way of those charged with waging the war. And in the case of the borderlands—effectively defined by U.S. authorities as one of the epicenters of the militarized battle against drug trafficking—it is a war of sorts against the region and the communities within.

Both Nicholas Ivie and José Antonio Elena Rodríguez died in the effort to stymie drug smuggling, as part of the “war on drugs,” one component of the multifaceted conflict waged by Washington in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. Their deaths and the shootings that caused them are tragic reminders that the “war” is actually not against narcotics, so much as it is against people—those actually involved in the illicit drug trade, those imagined to be, and those who just happen to be in the way of those charged with waging the war. And in the case of the borderlands—effectively defined by U.S. authorities as one of the epicenters of the militarized battle against drug trafficking—it is a war of sorts against the region and the communities within.

There is only one way out of the dead end that is multifaceted war (on drugs, crime, unauthorized migrants, and “terror”) in the borderlands: put an end to the hostilities, beginning with a program of gradual de-escalation and demilitarization.

Just this week, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the government of the Philippines signed a peace deal, ending decades of war. Meanwhile, in Oslo, Norway, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian government are set to begin peace talks today in relation to their more than 50-year conflict. That the parties to such seemingly intractable wars have shown a willingness to negotiate with the goal of achieving just and peaceful coexistence provides hope that things can and will be far different someday in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

Special thanks to Murphy Woodhouse for generously sharing his analysis and on-the-ground research.

Statement from the Tucson Sector Communications Division, United States Border Patrol (emailed to the author on Oct. 15, 2012):

On October 10, 2012, U.S. Border Patrol agents in Nogales, Ariz., responded to reports of two suspected narcotics smugglers near West International Street and Hereford Drive at approx. 11:30 PM MT. Preliminary reports indicate that the agents observed the smugglers drop narcotics load on the U.S. side of the international boundary and flee back to Mexico. Subjects at the scene then began assaulting the agents with rocks. After verbal commands from agents to cease were ignored, one agent then discharged his service firearm. One of the subjects appeared to have been hit. Agents notified the Government of Mexico (GOM) and secured the scene. U.S. Customs and Border Protection is fully cooperating with the FBI-led investigation.

Update (Oct. 17, 2012): The Southern Border Communities Coalition (SBCC) has learned that the U.S. government’s Office of the Inspector General will conduct an investigation of various cases of brutality or use of excessive force by agents of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the parent agency of the Border Patrol. The SBCC press release revealing the probe is available here.

Also available on the SBCC website is an annotated list of individuals killed or brutalized by CBP agents since the beginning of 2010.

Finally, Pedro Rios of the American Friends Service Committee, a member organization of the SBCC, has written a very helpful analysis of the growing number of cases involving excessive and deadly use-of-force by CBP agents, with a focus on the most recent cases, including that of José Antonio Elena Rodríguez. His analysis is available here.

Joseph Nevins teaches geography at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. Among his books are Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid (City Lights/Open Media, 2008) and Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on “Illegals” and the Remaking of the U.S.-Mexico Boundary (Routledge, 2010). For more from the Border Wars blog, visit nacla.org/blog/border-wars. Now you can follow it on Twitter @NACLABorderWars.