Bolivia returned to the international credit markets last month after an absence of nearly a century, selling $500 million in 10-year bonds at an interest rate of 4.875%. The country’s last global bond sale was in the 1920s, to finance expansion of the national railway network.

The event highlights the success of President Evo Morales's unique brand of economic pragmatism, as well as some ironic impacts of the global financial crisis.

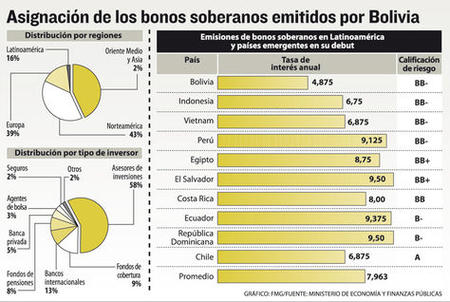

The bonds, sold by Bank of America’s Merrill Lynch and Goldman Sachs, were rated BB-, three notches below “investment grade.” Still, they were oversubscribed by a factor of more than eight, generating demand worth $4.2 billion from 267 international investors. More than 80% of the bonds were placed with North American and European buyers.

According to statistics provided by the Morales government, Bolivia is paying less on its new debt than many other countries with equivalent or better risk ratings, including Vietnam, Peru, and Chile. Bolivia’s borrowing rate is half of Venezuela’s, and considerably less than the Latin American average (7.963%).

According to statistics provided by the Morales government, Bolivia is paying less on its new debt than many other countries with equivalent or better risk ratings, including Vietnam, Peru, and Chile. Bolivia’s borrowing rate is half of Venezuela’s, and considerably less than the Latin American average (7.963%).

What explains this favorable global financial reception for the most impoverished nation in South America? For one thing, rating agency Standard and Poor’s gives Bolivia high marks for its strong macroeconomic indicators, relative political stability, and Morales’s prudent fiscal and monetary policies. According to S&P, Bolivia’s economy is now “one of the strongest among its peers.”

Since Morales’s election in 2005, Bolivia's economy has tripled in size. It is projected to grow at 5% or more for the third straight year in 2012, faster than the growth rates achieved by Brazil or Mexico.

International reserves have sky-rocketed from $1.7 billion to $12.7 billion under Morales and now constitute 50% of the GDP (Gross Domestic Product), providing an important buffer against economic downturns. Meanwhile, internal and external debt has dropped to 31% of GDP. For six straight years, Bolivia has achieved a fiscal budget surplus.

GDP per capita has nearly doubled since 2005, while the number of people living on less than $1 per day has fallen from 38% to 24%. Domestic demand is increasing rapidly. According to the World Bank, Bolivia is now a “middle income country.”

These strong indicators would seem to validate Morales’s unconventional—by market standards—economic policy, which has included the renationalization of strategic sectors divested by past neoliberal governments (such as hydrocarbons, telecommunications, and hydroelectricity). The vast increase in state hydrocarbons and mining revenues under Morales—also fueled by high commodity prices—is largely responsible for Bolivia’s economic prosperity and redistributive accomplishments.

These strong indicators would seem to validate Morales’s unconventional—by market standards—economic policy, which has included the renationalization of strategic sectors divested by past neoliberal governments (such as hydrocarbons, telecommunications, and hydroelectricity). The vast increase in state hydrocarbons and mining revenues under Morales—also fueled by high commodity prices—is largely responsible for Bolivia’s economic prosperity and redistributive accomplishments.

Still, S&P cautions that Bolivia’s overdependence on these sectors—which generate 70% of the country’s exports and more than 30% of government revenues—has contributed to its less than optimal credit rating. The country’s “high level of political turmoil” and continuing social conflict is cited as another negative factor.

Good timing has also played a role in Bolivia’s credit market success. As a result of the global financial crisis, with near-zero benchmark bond rates in the U.S. and Europe, a surplus of investor capital is chasing new, more profitable, investment opportunities in so-called “emerging market” economies. These countries—many of which have never sold debt before, or not for years—are now taking advantage of the lowest borrowing costs on record. Earlier this month, Brazil sold its bonds for 2.686%, an interest rate considerably lower than Bolivia’s. These rates were unheard of even a short time ago (which helps to explain the gap between Bolivia’s borrowing costs and those of other Latin American countries whose bond sales were completed earlier).

Some western analysts have seized on the perceived ideological inconsistency of Bolivia’s successful foray into the global bond market to vent their hostility against the Morales government. “Morales has the chutzpah, and three Wall Street institutions have the temerity, to issue bonds for a government that has personified twenty-first century Latin American socialism, and continues a time-honored tradition of expropriating foreign owned assets,” says Daniel Wagner of Country Risk Solutions.

In reality, economic pragmatism has been a consistent hallmark of the Morales government, despite its anti-capitalist rhetoric and political stridency. Even in such sectors as hydrocarbons, where the government has majority ownership and control, Morales has gone to great lengths to encourage private investment through incentives and guarantees to companies that are willing to participate on Bolivia’s terms. Six years after the Bolivia’s hydrocarbons nationalization, not a single foreign oil and gas company has pulled out of the country.

For Finance Minister Luis Arce, there is no contradiction between Bolivia’s state-led economic policy and its re-entry into the global credit markets. The bond sale, he says, is just another part of the government’s strategy aimed at resource recovery, industrialization, and poverty reduction.

“The issuance of bonds,” Arce explains, “is to help accelerate what we are already doing. Today we are showing the world that we have the ability [to successfully manage Bolivia’s economy]. And the great merit is that we are doing all of this on our own, without anyone’s help.”

“The issuance of bonds,” Arce explains, “is to help accelerate what we are already doing. Today we are showing the world that we have the ability [to successfully manage Bolivia’s economy]. And the great merit is that we are doing all of this on our own, without anyone’s help.”

Some Bolivian economists, including former Central Bank head Armando Méndez Morales, question why Bolivia should pay international creditors $24 million in annual interest for the next ten years, when it has substantial reserves and budget surpluses available. For Arce, this as an opportune moment to demonstrate Bolivia’s strong economic position to the world. “The objective of the bonds,” he says, “is to position Bolivia in the international community.”

What really matters, editorializes the daily Página Siete, is how the $500 million will be spent. The government has proposed to use the funds primarily for highway construction, a critical national priority (Bolivia, a country of 420,000 square miles, had only 2,200 miles of paved roads in 2000). Still, it would be more than ironic if the purveyors of global finance capital were to become the indirect patrons of the controversial TIPNIS highway, whose opponents are accused by Morales of conspiring with the very same transnational interests.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).