On November 15, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) and the delegates of the Colombian state will begin to tackle the first issue on their agenda: the agrarian question. My previous blog addressed the diametrically opposed narratives and positions on the agrarian question posed by the two contending forces and how this could unfold in the immediate future. In this blog I discuss the potential role of the Colombian military as spoilers to the peace process.

Since 1958 the military has enjoyed a wide margin of autonomy in managing security policy (policing, counterinsurgency, military justice and budgeting) with the founding of the National Front that ended a ten-year long civil war between the Liberal and Conservative parties. Granting the military autonomy was based on the agreement between the two mentioned parties barred the use of military officers as political pawns, as was the case during the civil war. This autonomy remained effective until 2002 when former president Alvaro Uribe Velez (2002-2006 and 2006-2010) introduced a national security doctrine (Democratic Security) that called for the militarization of society through a counterinsurgency strategy involving a million of informants and the so-called peasant-soldiers.

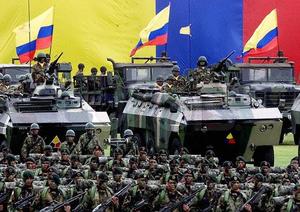

Since then, the civil-military relationship witnessed a shift in terms of determining military strategy in which civilian authority played a more active role. The military went along since this new strategy was not only influenced by the United States, but was also designed and funded through Plan Colombia. This $7 billion plan of mostly military aid boosted the political and economic role of the military. The result was the creation of a behemoth institution with an almost 500,000 soldiers and policemen, the second largest in Latin America after Brazil.

Now, with prospects of peace looming, the military has a number of worries. One is its human rights record and its organic links with the paramilitaries since the 1980s. The military is concerned that if a peace agreement is reached and amnesty is decreed this could be reversed, as were the cases of Chile and Argentina. In these two cases, the amnesties that were decreed in the 1980s eased the transition to electoral democracies, but years later the military was persecuted for crimes committed during their rule. In Colombia, the military committed more human rights crimes than all Latin America dictatorships combined; therefore the specter of a future prosecution is very real. This was illustrated by the retired Colonel Hugo Bahamon who the BBC quoted on October 24saying: look to what happened in Chile and Argentina where former soldiers 70 and 80 years old are imprisoned after reversing their amnesties. A noteworthy demand raised by Bahamon is his call to allow the military personnel to vote. If this were achieved, the military will exercise immense political power far exceeding any other political party or social force considering its size, organizational capacity, and relative ideological cohesion. Consequently, this will provide a further security guarantee to avoid the path of its Latin American counterparts. Ironically, however, is that while in 1958 the dominant parties agreed not to use the military in their infighting, now the military wants to meddle in party politics.

By airing these sentiments and desires, the Colombian military is openly expressing its concern and pressing for political guarantees that may go beyond what Chile and Argentina offered their respective soldiers. The coming months will reveal how these issues play out and whether the unmet sentiments will lead the military leviathan to spoil the peace process.

Next blog, I will address other equally important factor related to the military size and demobilization. Stay tuned.

Nazih Richani is the Director of Latin American studies at Kean University. He blogs at nacla.org/blog/cuadernos-colombianos.