Until recently, conventional economic wisdom held that sustained economic growth in any society could only be achieved at the expense of income equality. Today, even free market disciples like The Economist recognize that these goals are not contradictory—and that growing inequality, in fact, is an impediment to economic prosperity.

Recent data on economic growth and inequality for the United States and Bolivia reveal two starkly contrasting portraits.

The United States, after four decades of widening inequality, is experiencing the greatest economic downturn since the Depression. In 2011, while the economy grew by only 1.7% (down from 3% in 2010), income inequality increased by almost as much—the biggest single year increase in two decades. Over the past 30 years, the share of income held by the top 1% has more than doubled, increasing from 8% to 17%, while the share held by the bottom 20% has fallen from 7% to 5%. Currently, the United States has the highest level of income inequality of any developed country.

Poverty rates in the United States have risen 23% since 2006, now leveling off at 15.1%. Today, more Americans are living in poverty than at any time in the half-century since the census started publishing these estimates. Due to declining incomes, the U.S. “middle class” is eroding, dropping from 61% of adults 40 years ago to a bare majority now.

As Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has noted, the United States' declining middle class is too weak to support the consumer spending that has historically fueled our economic growth. Thus, inequality is “squelching our recovery”—but U.S. political leaders have been slow to act on this lesson.

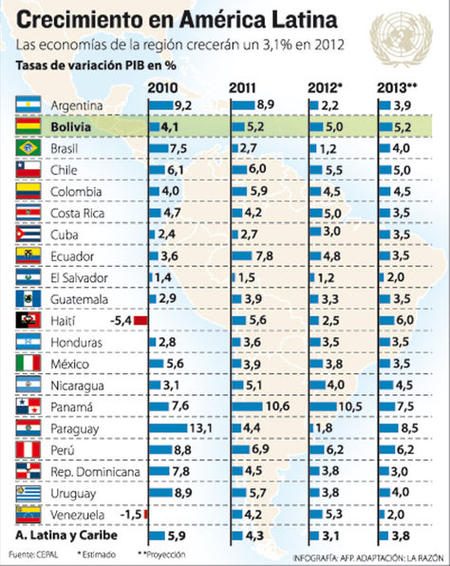

In contrast, despite the worldwide economic crisis, Bolivia’s economy is on track to increase by at least 5% in 2012, as it did last year. This is among the highest growth rates in Latin America, exceeded only by Chile, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela. Since the start of Evo Morales’s presidency in 2006, Bolivia’s GDP has tripled, and GDP per capita has more than doubled.

In contrast, despite the worldwide economic crisis, Bolivia’s economy is on track to increase by at least 5% in 2012, as it did last year. This is among the highest growth rates in Latin America, exceeded only by Chile, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela. Since the start of Evo Morales’s presidency in 2006, Bolivia’s GDP has tripled, and GDP per capita has more than doubled.

At the same time, according to data recently presented by Morales to the Legislative Assembly, income inequality in Bolivia has significantly decreased. In 2011, the richest 10% of the population had 36 times more income than the poorest 10%, down from 96 times more in 1997. “Bolivia is one of the few countries that has reduced inequality,” notes Alicia Bárcena, head of the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). “The gap between rich and poor has been hugely narrowed.”

Between 2005 and 2011, Bolivia’s poverty rate declined by 26% (from 61% to 45%). The extreme poverty rate fell even more, by 45%. An estimated 1 million people joined the ranks of the “middle class.” The World Bank has officially recognized Bolivia as a lower-middle income country, a ranking that affords more favorable credit terms.

Between 2006 and 2011, Bolivian workers’ purchasing power increased by 41%, as compared to 17% between 1999 and 2005. The minimum wage has risen 127% since 2005, far exceeding the rate of inflation. In contrast, U.S. workers’ real wages have stagnated or fallen, with inflation-adjusted incomes now at their lowest point since 1997. Since 1972, the average hourly wage has risen only 4%.

In Bolivia (unlike the United States), domestic demand fueled by rising incomes and narrowing inequality is a driving force behind the country’s economic prosperity. Local evidence of increased domestic consumption and consumer purchasing power can be seen in places like El Alto, the sprawling indigenous city overlooking La Paz, where banks and fast food outlets are sprouting up and the first supermarkets, shopping centers, and cinemas are being planned. In 2012, there were 8.9 million mobile phones in Bolivia (with a population of around 10.4 million). Construction activity has outpaced the capacity of the domestic producers, with cement now being imported from Peru.

Rating agency Standard and Poor’s gave Bolivia high marks for economic resiliency last October, in underwriting a successful $500 million bond sale—the country’s first venture into the international credit markets since the 1920s.

Behind these positive indicators is Bolivia’s state-led economic policy, including the re-nationalization of strategic sectors divested by past neoliberal governments (such as hydrocarbons, telecommunications, electricity, and some mines). Around 34% of the national economy is now under state control—although private investment (on Bolivia’s terms) is encouraged and has continued, in hydrocarbons and other key sectors.

The vast increase in hydrocarbons and mining revenues under Morales has funded a major expansion of social welfare programs, including highly popular cash transfers targeted to the elderly, pregnant mothers, and school children. It has also supported major infrastructure improvements, a significant increase in the coverage of basic services (such as water, electricity, and domestic gas), and a major expansion of public healthcare and education programs—all boosting the living standards of average Bolivians.

To be sure, Bolivia’s economic and redistributive policies are not free of problems and contradictions. As the Fundación Jubileo points out, more than 5 million Bolivians still live in poverty, and extreme poverty persists in rural areas. According to the labor research group CEDLA, the current minimum wage covers only 56% of the average family’s budgetary needs. Many believe that the government should be doing more to alleviate poverty and raise living standards, especially with international reserves now at record levels of $14 billion (58% of GNP).

More fundamentally, Bolivia’s extreme dependence on the hydrocarbons and mining sectors (which now account for 87% of total export earnings) makes the economy vulnerable to the vagaries of commodity prices, and has led to increasing conflicts with indigenous and environmental groups over the adverse impacts of extractive projects. Industrialization, which would at least enable Bolivia to export more value-added goods derived from these sectors, is a major priority of the Morales government but projects have been slow to get off the ground. “What we’re not seeing,” says Bolivian economist Horst Grebe, “is a transformation of the productive economy that is sustainable in the long term.”

Still, in the short run, Bolivia’s achievements in combining economic growth with greater income equality are impressive. The United States could learn a lot from Bolivia's example.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).