Lately, Bolivian Vice-President Alvaro García Linera has seemed to embody, in living form, the growing contradiction between his government’s international championship of environmental and indigenous rights, and its vigorous domestic pursuit of extractivist economic policies.

As a featured speaker on June 9 at New York City’s Left Forum—an annual gathering of leftist intellectuals and activists, convened this year to address the theme of “Mobilizing for Ecological/ Economic Transformation”—García Linera affirmed that the global battle for climate justice (in which Bolivia has played a leadership role) is a critical, anti-capitalist struggle. But just weeks earlier, at an international energy convention in Santa Cruz, he announced that the government of indigenous president Evo Morales intends to explore and exploit oil and gas resources in Bolivia’s national parks, many of which are collectively titled as indigenous territories.

As a featured speaker on June 9 at New York City’s Left Forum—an annual gathering of leftist intellectuals and activists, convened this year to address the theme of “Mobilizing for Ecological/ Economic Transformation”—García Linera affirmed that the global battle for climate justice (in which Bolivia has played a leadership role) is a critical, anti-capitalist struggle. But just weeks earlier, at an international energy convention in Santa Cruz, he announced that the government of indigenous president Evo Morales intends to explore and exploit oil and gas resources in Bolivia’s national parks, many of which are collectively titled as indigenous territories.

The new policy will include incentives to provide a “rapid return on investment” for the transnational companies (including Brazil’s Petrobras, Spain’s Repsol, and France’s Total) that have operated Bolivia’s hydrocarbons concessions in partnership with the state since the sector was nationalized in 2006, along with measures to expedite regulatory approvals and mitigate environmental risk. Expanding the hydrocarbons frontier into protected areas is necessary, according to García Linera, to guarantee Bolivia’s energy security and sovereignty in the face of growing domestic and external demand.

Invoking the theme of “resource nationalism,” García Linera has justified the government’s new hydrocarbons policy as an anti-imperialist strategy. “Curiously, a good part of this strip where there is gas and oil was declared parks in neoliberal times,” he noted in Santa Cruz. “They did it to keep the reserves for people from outside, from the north, and above.”

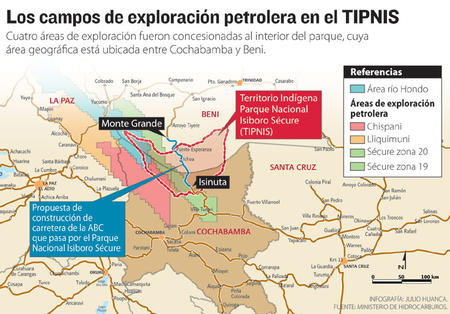

According to the civil society organization CEDIB, the land area conceded to gas and oil companies in Bolivia has vastly expanded under Morales, up from 7.2 million acres in 2007 to 59.3 million acres in 2012. Eleven of Bolivia’s 22 national parks currently include hydrocarbons concessions (although activity in these areas has been largely paralyzed, up to this point). Seven parks—including the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS), site of a protracted battle over the proposed construction of an inter-departmental highway—have concessions covering at least 30% of their land area. Four parks are at least 70% consumed by concessions and are at risk of disappearing entirely once these become operational.

To be sure, the Morales government has vastly increased Bolivia’s share of hydrocarbons revenues, with an effective take (through taxes and royalties) of 72%, among the highest in Latin America.[1] Since nationalizing the sector in 2006, Bolivia has earned more than $16 billion in hydrocarbons revenues, as compared to just $2 billion from 1999-2005, supporting a significant expansion of redistributive programs. Still, for those concerned with climate justice and indigenous rights as well as immediate poverty reduction, the conflicting discourses of García Linera and other government representatives are increasingly difficult to reconcile.

Outside Bolivia, the critique of these contradictions tends towards over-simplification and righteous indignation—as demonstrated by the leaflet distributed by the League for the Revolutionary Party at the Left Forum, attacking García Linera as an “enemy of Bolivia’s workers and indigenous peoples.” Inside Bolivia, where, as anthropologist Bret Gustafson has noted, gas is viewed primarily through the lens of resource nationalism, and as a ticket to economic prosperity, an anti-extractivist position is more difficult to maintain. From the Gas Wars of 2003 and 2005, the Morales government can point to a popular mandate to extract and commercialize Bolivian gas for Bolivians—notwithstanding that 80% of Bolivia’s gas is currently exported to Brazil and Argentina, and that industrialization has proved difficult to accomplish.

indignation—as demonstrated by the leaflet distributed by the League for the Revolutionary Party at the Left Forum, attacking García Linera as an “enemy of Bolivia’s workers and indigenous peoples.” Inside Bolivia, where, as anthropologist Bret Gustafson has noted, gas is viewed primarily through the lens of resource nationalism, and as a ticket to economic prosperity, an anti-extractivist position is more difficult to maintain. From the Gas Wars of 2003 and 2005, the Morales government can point to a popular mandate to extract and commercialize Bolivian gas for Bolivians—notwithstanding that 80% of Bolivia’s gas is currently exported to Brazil and Argentina, and that industrialization has proved difficult to accomplish.

While the lowland and highland indigenous federations CIDOB, CONAMAQ, and APG, whose constituents will be most adversely affected, have been quick to denounce the new policy, their demands are strategically focused on securing a new law of popular consultation, which they insist must be implemented before any hydrocarbons activities are permitted on indigenous lands. The Morales government’s efforts to develop a prior consultation law, which date back at least two years, are currently stalemated due to conflicts with these sectors, who claim they have not been adequately represented in the process.

Wary of the pitfalls experienced during the flawed TIPNIS consulta, the federations insist that the government must be obligated to seek the free, prior, and informed consent of affected communities, through a process carried out in good faith in accordance with traditional community norms and procedures, as required by international law and the Bolivian constitution. Lately, the government seems more concerned with expediting the consultation process, as evidenced by its recent proposal to limit the consulta to 120 days.

For groups engaged in the struggle against the TIPNIS highway, the new hydrocarbons policy confirms what most have long suspected—that the advancement of gas and oil interests is a major factor behind the push for the road. Within the TIPNIS there are 4 outstanding concessions, including the Sécure bloc which is virtually adjacent to the proposed highway.

Curiously, while the law protecting the reserve as “untouchable” remains in effect, the Morales government recently announced that YFPB Petroandina, a joint venture between the state energy company and Venezuela's PDVSA, will begin the necessary steps to secure an environmental license for exploratory activities inside the park. Ironically, as activist Pablo Rojas has lamented, only eight years ago Morales (as head of the Chapare cocalero federations) led the successful struggle, along with native TIPNIS residents, to block Repsol’s operations in the reserve.

Curiously, while the law protecting the reserve as “untouchable” remains in effect, the Morales government recently announced that YFPB Petroandina, a joint venture between the state energy company and Venezuela's PDVSA, will begin the necessary steps to secure an environmental license for exploratory activities inside the park. Ironically, as activist Pablo Rojas has lamented, only eight years ago Morales (as head of the Chapare cocalero federations) led the successful struggle, along with native TIPNIS residents, to block Repsol’s operations in the reserve.

In his recent treatise Geopolitics of the Amazon, García Linera sheds further light on the seeming contradiction between the Morales government’s extractivist policies and its commitment to environmentalism and plurinationalism. Building highways and drilling for gas, he argues, are essential tools to advance the sovereign revolutionary state, bolstering its capacity for survival in the face of ever-present external and internal threats. This goal, he suggests, must take priority over all others.

Further, he explained at the Left Forum, while indigenous groups offer a vision of living in harmony with nature that suggests the future potential for communitarian socialism, they also have pressing current needs for education, health care, food, and shelter that can only be met through reliance on extractive activities. It is a contradiction, he suggests, that will only be resolved through struggle. On that point, most everyone can probably agree.

[1] George Gray Molina, presentation at Latin American Studies Association conference, Washington DC, June 1, 2013.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).