Over the past decade, thousands of people have died in the desert borderlands of the United States. As has been demonstrated repeatedly, the deaths are a result of U.S. border enforcement policies that have made border crossings much more dangerous than they were before the era of border militarization. But the number of deaths is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to understanding the ugliness unfolding on the border. Hundreds are unidentified, hundreds are missing, and distraught relatives are getting lost in the spaces between the various bureaucracies that can’t or won’t help.

One of these family members, Reyna, last spoke with her husband, Felix, on July 8, 2009. He called her from Altar, Sonora, to tell her that he would be crossing the border into the United States the following day. Having been deported to Mexico the previous May, he was in a hurry to get back to her, since she was struggling to make ends meet alone with two small children.

A few days after Felix’s call, Reyna got a call from his coyote, or professional smuggler. Felix didn’t make it. He had collapsed in the desert and was left behind somewhere near a road frequented by the Border Patrol near a place called Choulic.

In the summer of 2011, almost two years after Felix went missing, a friend and I visited Reyna and her children in their home in rural North Carolina. Finding her was difficult. She could not read or write or give me directions. As we drove around in circles in a rural area, we began to notice white feathers all over the grass outside the car. By the time we turned down Reyna’s road, the feathers were covering the ground and the air was thick with the stench of chemicals, manure, and blood from a nearby poultry processing plant. Reyna’s home was one of about a dozen trailers lining an unpaved loop. At the entrance to the loop was a small, dilapidated shack with a sign outside reading Tienda. The windows were covered with ads in Spanish for international calling cards.

We sat with Reyna for about an hour and a half as she described what had happened, what Felix was wearing, the color of the metal restorations on his front teeth, the fact that he’d had a bad knee and how that was what had probably gotten him into trouble in the desert. We learned that she worked for the poultry processing plant and that she and her children were undocumented. Her living conditions, likely on company land, were dire. Reyna’s children, an eight-year-old boy and a five-year-old girl, clung to her and whispered in her ear as we spoke. Her son gently pulled a small cockroach out of her hair and wiped the tears off her face as she described to us how the ordeal had affected her family:

“It has been so hard. We suffer so much. We don’t know anything. He wanted to be with his wife. He wanted to be with his kids. And they love him so much. And they need their papa. And I need him. They need new things. They say, ‘Mama, I want new clothes, I need a backpack.’ I have to work all night and into the day to pay the rent. And we have two children in Guatemala. Without knowing where he is, I don’t know what to do. I can’t do it all by myself. For two years now, we know nothing of him.”

I met with Reyna for two reasons—to collect more information about Felix so that he might be identified among the unidentified bodies at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner (PCOME), and to inform my dissertation research on death, disappearance, and identification on the U.S.-Mexico border. Felix’s case is one of many collected from families, foreign consulates, and immigrant rights and humanitarian groups as part of the Pima County Missing Migrant Project (PCMMP), which sought, beginning in 2006, to organize all such data for southern Arizona. The project now has records for nearly 1,400 missing persons last seen alive crossing the border.

Relatives of the missing, like Reyna, are calling agency after agency for help. Some have called more than 20 different offices. Most of these calls are never returned. The calls that do come are from mysterious people claiming to have the person, willing to release them only after thousands of dollars have been wired to them. Other calls come from private investigators, promising to unearth hidden information—again for a price.

The data provided by relatives to various agencies are inconsistently shared with others, especially with medico-legal offices tasked with investigating the deaths of bodies found in the desert. Although the PCMMP has successfully organized most of these data for Arizona, border-wide, the problem continues. There is no centralized repository for all reports of missing persons last seen crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Hence, a family could report a missing person to an office in one state, while the body is discovered in another. There is still no consistent way for these records to be connected.

This is not just a border problem, but a national one. In 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice launched the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), an online relational database designed to match missing person reports with records for unidentified decedents found throughout the country.

Although NamUs is enormously useful, it relies on local jurisdictions to enter their own records for unidentified remains, and many medico-legal offices still do not use the system. The PCOME, an office with exemplary practices, uploads all cases of unidentified remains into NamUs. But the full potential of NamUs is not reached unless information is entered for both unidentified remains and missing persons. Until recently, NamUs could not accept reports for most missing migrants because a police tracking number was required, and U.S. police agencies usually will not take reports for missing foreign nationals. In addition, many relatives of missing migrants will not call police for fear of deportation, which could lead to further family separation.

In the summer of 2012, the PCOME became the first non-police entity authorized to enter missing person reports into NamUs. With a backlog of 1,400 cases, the data entry is taking considerable time. However, with only about 400 of the cases published, identifications are already being made, and families with whom the project had lost contact are finding their reports online, then calling and providing more information.

Despite these strides, there are problems. Although NamUs has granted the project access, coming up with funding for the work of getting the reports into NamUs is challenging, because the federal and state agencies that typically support this type of work cannot use their money on missing foreign nationals. Moreover, even when all the information is complete, NamUs will not resolve all the cases. NamUs uses non-genetic information to make connections between unidentified and missing—the date of disappearance and date of death, the clothing the person was wearing, the dental condition, scars, tattoos, and so forth. Because such a large number of the unidentified are highly decomposed or skeletal, and because there is so little information about many of the missing migrants, a large portion of the cases will never be resolved without comparing DNA taken from the body to DNA taken from relatives of the missing person.

The PCOME has taken DNA samples from all the unidentified decedents discovered over the past decade. These samples are sent to Bode Technology Laboratories in Virginia, where DNA is extracted, profiled, and entered in a database. To identify remains in this context, an identification hypothesis is first made between a particular missing person and a particular unidentified body. Then a one-to-one comparison is made using DNA profiled from the family and DNA profiled from the remains.

Thanks to the efforts of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF), a massive comparison system capable of producing blind matches is in progress. EAAF’s Border Project has the goal of creating a regional system, including Central America, Mexico, and the United States, to centralize the exchange of information about missing migrants and unidentified remains. In collaboration with governments and nongovernmental organizations, EAAF has created DNA banks for families of missing migrants in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Chiapas, Mexico. The DNA sequenced from these families is then sent to Bode Technology, the same lab where PCOME sends DNA sequenced from the unidentified dead. Dozens of identifications have already come out of this work.

While this is good for the PCOME and the families who live in one of the areas where EAAF has established (or will establish) a DNA bank, there are enormous challenges to addressing the problem on a border-wide, regional scale. For many cases of unidentified remains discovered in the United States, DNA data are uploaded into the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). But DNA samples taken from families of missing migrants cannot go into this system for comparison because by law, the DNA must be collected by a U.S. law enforcement agency, and most law enforcement agencies are not taking these reports for reasons discussed above. Also, for a variety of reasons, CODIS does not have DNA for anywhere near all cases of unidentified remains discovered along the border. Through conversations with families and officials in other counties, I have learned that some medico-legal offices are not taking samples for DNA before remains are buried as unknowns. Also, the requirements for entering DNA data into CODIS are very high, and for cases of weathered bone, which may not produce a complete profile, the data cannot be uploaded.

The point is that the DNA taken from the bodies is not being compared with DNA taken from the families on any massive scale. Those of us working toward a comprehensive system to help the families of the missing are coming up against massive bureaucratic, transnational roadblocks. The result is that hundreds, likely thousands, of family members are still waiting for word about their missing loved ones, while in the meantime the bodies are being found, examined, and buried or cremated as unknowns. Even if a family reports someone missing immediately, and even if the body is found right after death, the two events will very likely not be connected.

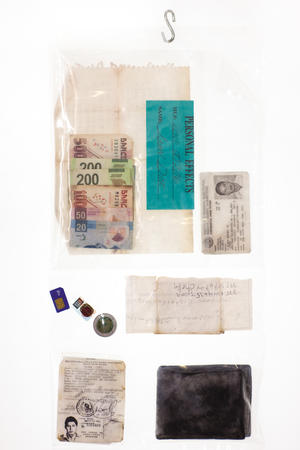

Reyna reported Felix missing to both the Guatemalan and the Mexican consulates; although he was Guatemalan, he used a Mexican alias and false ID. Indeed, when meeting with Reyna, I saw that there were two reports for Felix in the project list of missing persons—one in his real name and the other under his alias—but neither had the correct date of disappearance in the desert.

When I returned to Tucson from North Carolina, I searched among the unidentified dead for Felix, not expecting to find anything. It had already been two years, and it was likely that his body either had not been found or was so highly decomposed that I would not be able to find him without DNA. But when I opened the binder full of unidentified-persons reports to July 2009, there was a man, found near Choulic, Arizona, on July 9 with metal restorations on his front teeth. I recognized Felix from the photos Celia had given me. I called her in North Carolina and told her that I might have found him. She walked down the road to the tienda, called, told me the e-mail address of the person working there, and within a few minutes was looking at a photo of her husband, taken the day after he died in 2009.

Due to errors in taking data from the family, Felix had remained unidentified for over two years. His body was kept in the morgue at PCOME for nearly a year and was then released as unidentified, with a number rather than a name. He was cremated and his remains were kept in the Pima County Public Cemetery in Tucson among hundreds of others, until he was finally identified. Reyna asked for Felix’s remains to be sent to her in North Carolina, rather than to Guatemala, because, she said, it was their home and it was where he wanted his family to be. He had wanted his children to have the opportunities that growing up in the United States could provide.

For Reyna, two years of anguish were over. For me, frustration, anger, and guilt followed the phone call. Felix’s case was representative for me of the many ways my hands are tied when it comes to helping the families of the missing. If we had had NamUs as a tool at the time, the records likely would have been linked earlier. If forensically trained people rather than consular officials had been taking the information, maybe the data would have been of better quality. If we had had a DNA matching system, Felix’s family would have been able to submit DNA and probably get an answer much sooner than they did.

But Reyna did finally find out, and was able lay her husband to rest and tell her children what had happened to their father. Hundreds of others are still waiting for news. The daily experiences of exclusion that immigrants like Reyna and Felix go through are repeated in this context, where they are excluded from the technologies and systems that have been designed to address the basic human right to know what happened to a missing loved one. The poultry processing plant and Reyna’s run-down trailer are inseparable from Felix’s death and disappearance in the desert. The suffering of the families of the missing is a call not only to identify the dead but to recognize that these people too are loved, missed, and irreplaceable.

Robin Reineke is a doctoral candidate in the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona and Director of the Pima County Missing Migrant Project at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner in Tucson, Arizona.

Read the rest of NACLA's Summer 2013 issue: "Chavismo After Chávez: What Was Created? What Remains?"