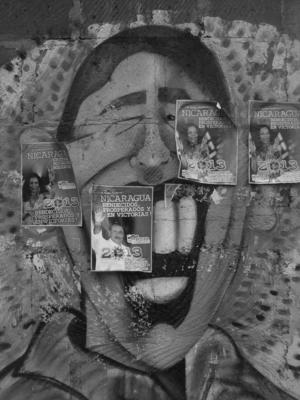

Long described as a city “drowning in garbage,” Managua is ground zero in the fight against unsightly municipal solid waste in Nicaragua. The completion of a large-scale international development project involving the capital city’s only waste site in February 2013, together with the announcement of the Vivir Bonito (Live Pretty) national health and well-being campaign a month earlier, may be changing the ways Nicaraguans think about garbage. While striving to improve the city’s physical environment, these recent developments may also change the ways the environment, public health, and, more broadly, citizens are governed.

Across Latin America, increasing urbanization and the adoption of the global throwaway culture further strain municipal waste collection that is already slowed by lack of capital, a surfeit of politicking, and enormous infrastructural barriers.1 Of the approximately 1,500 tons of garbage produced daily in Managua, 300 tons remain uncollected and end up in the city’s drainage canals or in one of hundreds of illegal, spontaneous dumps located throughout the city.2 The garbage that is collected is deposited by the city at one location: La Chureca, an epithet for Managua’s municipal waste site, meaning “old rag.”

Prone to occasional flooding and measuring approximately 116 acres, La Chureca is located in barrio Acahualinca, northwest of the city along the bank of Lake Managua (Lago Xolotlán). The site began receiving municipal solid waste around the time of the catastrophic 1972 earthquake that leveled much of downtown Managua. It was privately owned until February 2011, at which time the government seized the dump to prevent stalling on a planned development project. For nearly four decades, neither its owners nor the city regulated the open-air waste site producing numerous environmental problems including air, water, and soil contamination. La Chureca also became synonymous with innumerable social ills. Approximately 250 families lived next to and on top of the garbage. Additionally, more than 1,500 men, women, and children churequeros (trash pickers) worked in the dump, picking over the garbage to collect, classify, and sell recyclables. La Chureca was not only a serious health risk to people living or working there, but was also often considered by outsiders to be synonymous with prostitution, drug use, and thievery, as well as extreme poverty. As a result, the dump “earned” the title of one of the Most Horrendous Wonders of the World.3

A visit to La Chureca by the vice-president of Spain, María Teresa Fernández de la Vega in August 2007 marked a turning point in the site’s history. Stating that “no politician can set foot in La Chureca and forget it without doing anything,” Fernández de la Vega announced the Barrio Acahualinca Comprehensive Development Project in January 2008.4 The $45 million, four-year project, designed and implemented by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development (AECID), intended to convert the open-air waste site into a “modern sanitary landfill,” construct a state-of-the-art recycling facility employing on-site hundreds of churequeros, and relocate people living in La Chureca to a planned housing development.

Interviews with trash pickers in mid 2009 revealed a deep skepticism of the project. Many expressed doubts the project would even begin, let alone finish. A resident of La Chureca told me, “I’ve always heard that help is coming, that it is coming from this country or that country, and so we just say, save yourself if you can.” More commonly, however, trash pickers expressed concern that the project, which was expected to employ only 400 to 500 people, would favor pickers living in La Chureca over those living around the perimeter of the site.5 Speaking to this concern, a trash picker ardently told me, “Everyone can survive (off La Chureca). If it is taken away, what will all the people do? If there aren’t jobs, then I don’t want them to take it away.”

La Chureca’s redevelopment was completed in February 2013. Two hundred fifty-eight homes were built for trash pickers, the dump was sealed, dozens of extraction wells to collect emitted methane were installed, and the newly constructed recycling plant, capable of processing 140 tons of garbage per hour, welcomed the old churequeros as modern industrial employees. AECID commented, “Thanks to the new recycling plant, the city of Managua is able to regulate the management of urban waste, making it sustainable and profitable.”6 El Salvador’s vice minister for environment and natural resources, who visited the site with a contingent of Central American and Caribbean politicians, noted, “Frankly, this (La Chureca) is an extraordinary experience.”7

Despite the project’s environmental benefits, community leaders warn that “things remain critical” in barrio Acahualinca. In July 2013, during an event at which AECID was to turn over the landfill to the city of Managua, trash pickers without jobs picketed the Municipal Company for the Comprehensive Treatment of Solid Waste (EMTRIDES), the city-owned company created to manage the landfill. The protest, however, was short-lived. The group disbanded after being promised their needs would be met “later.”8

As of August 2013, the needs of many former churequeros had not been met. Results from a randomized household survey in three communities located adjacent to the dumpsite revealed the gravity of the economic impacts wrought by the completion of the sanitary landfill. Trash picking in La Chureca was the primary income for three-fourths of interviewed houses. However, in approximately half the homes in which at least one person previously worked in La Chureca, not one person was hired by EMTRIDES. The situation is particularly serious in the communities of Alemania Democrática and COPRENIC, in which an average of 1.6 people per home lost their livelihood. Moreover, more than eight out of ten former waste trash pickers not hired by EMTRIDES are unemployed. Such an extreme increase in unemployment contributes to concerns about an increase in alcohol and drug use. Additionally, community members complain that illegal dumping sites, from which unemployed waste pickers now earn their livelihood, are proliferating in the streets.

Even for those trash pickers hired by EMTRIDES, the economic situation is grim. The dearth of job opportunities in the new plant means that no more than one person per household was hired—except in cases of alleged cronyism. In the plant, the vast majority of churequeros work alongside one of two large conveyor belts onto which garbage is dumped. They earn $5,040 córdobas (US $206) per month, roughly equal to the national minimum wage for industry-related work and well below the June 2013 “food basket,” valued at about (US $462). More than half the trash pickers interviewed in this household survey indicated that their earnings are less than or equal to what they earned as pickers. Furthermore, EMTRIDES employees have yet to receive the solidarity bonus (bono solidiario), intended to supplement the salaries of low-earning government employees.

*

In January 2013, one month before the completion of the Barrio Acahualinca Comprehensive Development Project, Nicaragua’s First Lady Rosario Murillo announced the start of the “Live Clean, Live Healthy, Live Pretty, Live Well!” (“Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien!”) national campaign. The campaign, nicknamed Vivir Bonito, is the hallmark of the new cabinet post of Family, Community, and Life, which was created through a constitutional amendment. Vivir Bonito calls upon Nicaraguans to rethink and change individual behaviors so as to promote individual, community, and national health and well-being. The “Basic Guide” of Vivir Bonito is comprised of 14 detailed guidelines that intimately link individual health and wellbeing to cultural, political, and social identity, community and national health, and environmental stewardship.

Waste governance plays a key role in meeting Vivir Bonito’s environmental stewardship goals. Implicitly, it seems that waste governance is at the heart of statements like this one from guideline number one: “We learn…simple and practical norms for living together…among Familial and Community Spaces, Public and Private Spaces, where we observe Cleanliness, Hygiene, Order, Aesthetics, Respect, Loving Care, and Permanent Solidarity.”9 Guideline number nine explicitly mentions that municipalities and communities should promote “norms of consumption and garbage elimination that address judicious and respectful conduct of Natural, Environmental, Cultural, Personal, Familial, and Community Rights so as to promote the Nice and Better Nicaragua that all men and women want.”10 The goals go on to state that these actions are to be taken because it is a “Right to Live Clean, Healthy, Pretty, Well…”.

Central to the plan is citizen participation and individual responsibility for waste management to “guarantee our homes and communities, public and community spaces…are clean, salubrious, pretty, and that they offer the best image of us and the Nation” (emphasis added). It is individual members of the Sandinista Youth Movement (Juventud Sandinista) and Citizen Power (Poder Ciudadano) who are expected to lead anti-litter campaigns and educate Nicaraguans about the harm of littering in Managua and throughout Nicaragua. In effect, the Ortega administration is using politically loyal citizen groups to serve as “multipliers of knowledge,” much like the FSLN did for literacy and public health campaigns following the 1979 revolution.12 Citizen groups are expected to take on the responsibility of ensuring that their neighbors participate in educational programs and incorporate correct health practices into their everyday lives. More broadly, then, these educational campaigns can be viewed as an extension of the Nicaraguan state’s role in governing the country’s population.

The Mayor’s office has implemented a number of tactics to discipline citizens’ behaviors vis-à-vis solid waste management legislation. In March 2013, the Managua City Council unanimously passed the Municipal Ordinance about Environmental Damages and Fines. This law, which was implemented immediately, prohibits garbage, liquid, gaseous, visual, and noise pollution, as well as damage to forests. Managua’s Mayor, Daysi Torres, “indicated that the object of the ordinance is standard: to sanction and control the conduct of persons who generate whatever type of environmental contamination, causing deterioration to the hygiene of the population of the municipality of Managua.”13 Persons and businesses caught violating this law will be fined 100 córdobas to 100,000 córdobas (US $4 to US $4,000) depending on the type of pollution and the degree of environmental damage their specific violations are suspected to cause. Mayor Torres stated, “For four years a clean-up campaign was implemented to educate the population, but they continue dirtying and damaging the environment. Whether they are rich or poor, nobody will be spared a fine if they violate (the ordinance).”14 Stressing that the new law will be applied with a mano dura, the mayor’s office already made an example of the Organization of American States (OAS) and several private businesses by leveraging stiff fines. Municipal Ordinance 02-2006 has also spurred the establishment of la línea verde, a green telephone line to report persons and businesses that pollute Managua.

*

These recent developments indicate that garbage is a rallying point for the Ortega administration. Garbage collection is a political tool that is being used to represent and promote modernity and, by extension, capitalist development.15 First Lady Rosario Murillo commented, “Private business is interested in a clean, pretty, safe country with happy families; there is no business strategy that can develop itself in an insecure country, in a country that it is not healthy, in a country that is not clean.”16 Concretely, the recycling plant represents an opportunity for the city of Managua to profit from the value of recyclables—estimated at (US $40 million)—collected annually in the capital.

The collateral effects of solid waste modernization must, of course, be considered—especially the unintended consequences for marginalized communities. For instance, initial data discussed above suggest that hundreds of trash pickers have been displaced and that the economic and social landscape of trash picker communities has been profoundly altered. In addition, it is unclear how Municipal Ordinance 02-2006 will be applied to the many low-income barrios that lack infrastructure, including adequate public or private water, sewage, and solid waste management services.

On the other hand, the incorporation of solid waste management into Vivir Bonito suggests that it is being used to help shape and transform social, cultural, and political values of contemporary Nicaragua. These appear to be the “Christian values, socialist ideals, and solidarity practices” omnipresent in Ortega administration publicity.17 The pivotal question is whether this program represents a veneer of current neoliberal political economy or is indicative of steps toward a post-neoliberal future.18

1. Martin Medina, The World’s Scavengers (Lanham, MD: Altamira Press, 2007).

2. Anna Pérez Rivera, “La ciudad capital estrena botaderos de basura,” La Prensa, January 5, 2009, accessed October 15, 2013, http://archivo.laprensa.com.ni/archivo/2009/enero/05/noticias/nacionales....

3. William Grigsby Vergara, “The ‘new’ Chureca: from garbage to human dignity,” Revista Envio, Number 321, April, 2008. See also, Tim Maurer, “Hope in Hell on Earth, micro-finance in Nicaragua,” Forbes, July 26, 2012, accessed September 10, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/timmaurer/2012/07/26/hope-in-hell-on-earth-m....

4. Edgard Barberena, “Avanza el proyecto de área verde La Chureca,” El Nuevo Diario, Feb 1 2008, accessed January 17, 2013, http://impreso.elnuevodiario.com.ni/2008/02/01/contactoend/69228.

5. Christopher D. Hartmann, “Uneven urban spaces: accessing trash in Managua, Nicaragua,” Journal of Latin American Geography 11:1 (2012).

6. AECID, “La Chureca, del vertedero a gestión racional de residuos,” last modified February 19, 2013, http://www.aecid.es/es/noticias/2013/02-2013/2013_02_19_la_chureca_de_ve....

7. Jessie Ampié, “La Chureca procesará 140 toneladas de basura por hora,” El Nuevo Diario, November 24, 2012, accessed October 1, 2013, http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/270253.

8. Jessie Ampié, “España entrega relleno sanitario,” July 13, 2013, accessed October 2, 2013, http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/257710.

9. El 19 Digital. 2013. “Estrategia Nacional para “Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien... !” January 25, 2013, accessed January 27, 2013 http://www.elpueblopresidente.com/EL-19/14873.html.

10.El 19 Digital, “Estrategia Nacional para “Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien... !””.

11. El 19 Digital, “Estrategia Nacional para ‘Vivir Limpio, Vivir Sano, Vivir Bonito, Vivir Bien’”.

12. Ministerio de Salud del Poder Ciudadano, “Plan de Acción de Manejo de Basura 2012,” October 15, 2012, accessed January 27, 2013, http://www.minsa.gob.ni/index.php?option=com_remository&Itemid=52&func=s...

13. Rafael Lara, “Multas altas a quienes contaminen,” El Nuevo Diario, March 23, 2013, accessed March 28, 2013, http://www.elnuevodiario.com.ni/nacionales/281419-multas-altas-a-quienes....

14. ibid.

15. Sarah Moore, “The excess of modernity: garbage politics in Oaxaca, Mexico,” Professional Geographer, 61 (2009): 426-37.

16. El 19 Digital, “Compañera Rosario invita a familias nicaraguenses a enfrentar juntos el desafîo de vivir en una Nicaragua mejor,” February 5, 2013, accessed February 6, 2013, http://www.elpueblopresidente.com/EL-19/15136.html.

17. José Adán Silva, “¿Qué hay detrás de “Vivir bonito”?,” La Prensa, March 10, 2013, accessed March 22, 2013, http://www.laprensa.com.ni/2013/02/08/reportajes-especiales/133870-que-h....

18. Eduardo Gudynas, “Development Alternatives in Bolivia: the Impulse, the Resistance, and the Restoration,” NACLA Report on the Americas, 46 (2013): 22-26; Arne Ruckert, “The World Bank and the poverty reduction strategy of Nicaragua: toward a post-neoliberal world development order?,” in Post-neoliberalism in the Americas, eds. Laura Macdonald and Arne Ruckert. (New York: Palgrave, 2009), 135-50.

Christopher D. Hartmann is a Ph. D student in the department of geography at Ohio State University.

Read the rest of NACLA's Winter 2013 issue: "Latino New York"