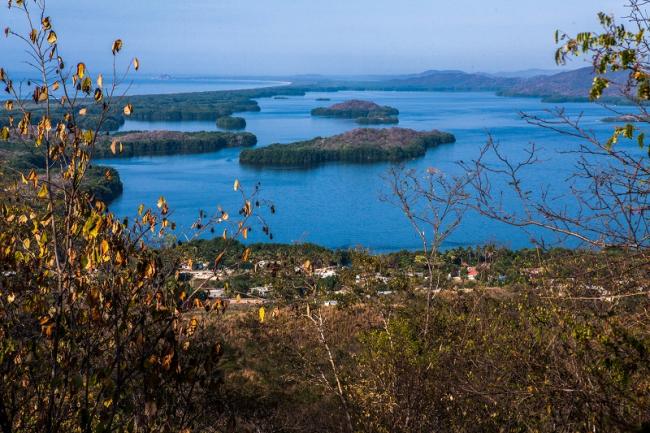

“Here in our lagoon, we do not have fish anymore. We had huge amounts of prawns but now they are difficult to find, and the mussels are not edible,” explains Cirila Martínez, member of the Mangrove Fisherwomen’s Cooperative and resident of Zapotalito, a community neighboring the Pastoría lagoon in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Twenty years ago, the Pastoria lagoon was a healthy ecosystem. It provided food and income to approximately 2,000 fishermen and women and their families. But the lagoon has changed rapidly. Species are dying or migrating at a fast pace. Water is highly polluted, and it is increasingly difficult for residents to survive from fishing. The lack of fish is leading to migration within the population. The Cooperative is organizing to protect and restore the ecosystem, after years of government neglect.

The Pastoría belongs to the coastal lagoon complex of Chacahua, designated a Ramsar Site by the Convention on Wetlands in 2008. This status highlights its significant value for humanity. Mangroves serve as a nesting and breeding habitat for fish, shellfish, migratory birds, and crocodiles. These ecosystems are crucial to tackling climate change, as they dampen hurricane and tsunami impact, prevent coastal erosion, act as carbon sinks, and filter polluted waters. Nonetheless, an estimated 50 percent of these ecosystems have disappeared over the last 50 years. According to The Mangrove Alliance, without adequate intervention, these ecosystems could disappear completely in the next century.

“Women who refuse to leave have to take charge of the household under hash circumstances,” explains Angélica Gómez of Fondo Semillas, a feminist non-profit that has followed the work of the cooperative since its foundation.

Cristina Arellanes Martínez, president of the cooperative and mother of three children, is one of many area residents impacted by migration. Her husband was also a fisherman, and migrated to the United States two years ago, leaving her as the head of the family.

Migration is only one of the challenges facing the members of the Mangrove Fisherwomen’s Cooperative in an industry where they are often ignored. “We joined forces to empower ourselves and to make our work visible. We wanted people and institutions to realize women are also fishers,'' explains Arellanes.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the role of women in fishing is commonly underestimated, even though they represent 19 percent of this sector at the global level and 50 percent when combining the primary and secondary sectors. While fewer women are involved directly in the catching of fish, many others take part in the stages of preparation and commercialization. In the case of Mexico, 12 percent of fishers are women and 48 percent are involved at some stage of the cycle, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI).

Gender Inequality and Violence in the Fishing Industry

The Mangrove Fisherwomen’s Cooperative was founded in 2016 with 20 women. Since then, gender inequality and violence have been central aspects of their work. Through workshops, they have educated themselves on the rights of women. They have opened a space where they can speak freely, share their experiences as women and as fishers, explains Angelica Goméz of Fondo Semillas.

Gender inequality is visible within the community, through an unequal division of labor and a double burden. They are responsible for the housework, care of children and elders, as well as contributors or heads of the household economy. The National Council for Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) found in a study that women spend 2.5 more times on housework than men. According to Lucía Perez of the organization Gender Equality, Citizenship, Work and Family 30 percent have double shifts, where the second one is at home.

Cooperative member Brígida Martínez is the main breadwinner in her household despite a serious knee injury. Her husband suffers from health problems, leaving Brígida to provide for the family. Fifty-six-year-old Martínez wakes up every morning before sunrise to begin housework. After this, she makes her regular visits to nearby communities to sell raw and cooked fish.

To counter the obstacles and consequences of gender inequality and violence, the members of the cooperative have received psychological assistance. They agree the therapies have been helpful to overcome traumas and difficulties they face as women. “When I joined the group, I did not think something was going to change,” Brígida says. “But I was proven wrong. Before, I could not talk to anyone, nor could I look people in the eyes. I used to hide behind my job. I did not care about anything else.”

Violence against women is common in Zapotalito and Mexico more broadly. The National Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relationships (ENDIREH), reported that 66 of every 100 women have suffered at least one case of violence in their lives.

The cooperative is an instrument of solidarity and opposition to gender violence. The women support one another to break the silence so common in cases of abuse. Arellanes, president of the cooperative, explains, “When a woman suffers, you want to help her. Maybe you cannot economically, but you can advise her of where she can get help. I think that every woman suffers violence. In different ways, but we all experience it.”

Corruption and Environmental Racism

Oaxaca is the Mexican state with the second-highest Afro-Mexican population, including in Costa Chica, where Zapotalito is located. These communities have been historically excluded and were only recently recognized as an ethnic group. This lack of recognition has led to the violation of basic human rights, such as access to clean water.

Civil society organizations, such as La Ventana and Coopera, have reported allegations of environmental and institutional racism against these communities. They claim the Mexican government has neglected fishermen and women dependent on the Pastoría lagoon.

Public policy has benefited industrial-scale agricultural businesses, at the cost of the population. The courses of tributary waters have been changed to serve the needs of single-crop plantations. In addition, regulators have turned a blind eye to the use of pesticides damaging the environment. High levels of these substances have been found in the lagoon and are directly connected to mass fish death.

The Mexican government has also been criticized for undervaluing and ignoring local knowledge on natural resources management. The government has carried out inadequate infrastructure projects. “The works are not planned properly. They are poorly placed,” says Felipe Quiroz, ex-president of the Monitoring Committee of the Cerro Hermoso Canal Project.

“We observe daily how currents change. We tried to contribute and participate but they have never allowed it.”

The issues of infrastructure related to the lagoon and the ecosystem began in the 1970s. The government executed a plan to open the canal that connected the lagoon to the sea. Scientists have warned that this type of work threatens the existence of coastal lagoons, as they modify the natural hydrology of the ecosystem.

After this intervention, the environmental impact has worsened. Since 2001, the government has initiated dredge works and the construction of breakwaters. However, these projects have not been concluded and instead have been associated with acts of corruption. “The projects that took place between 2014 to 2017 only benefited the companies. You could say they only came here to loot resources,” says Quiroz.

Following the allegations presented to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, in 2019, Afro-Mexican communities were finally recognized by the government. Yet, their rights continue to be violated. The inhabitants of Zapotalito, along with four other communities, continue to wait for real solutions to the environmental and social problems associated with the lagoon.

In the first half of May 2021, following pressure from civil society, the dredge works finally made some progress. The lagoon is once again connected to the sea. However, the canal is not deep enough. Therefore, there are no guarantees of how long it will remain open. “It could work for a day, a month or a year,” explains Antonio Guzmán, municipal director of tourism and fishing.

Women Lead Restoration Activities

The obstacles faced by the cooperative reduced the number of members, from 20 to 12. Despite this, they remain motivated to look for alternatives. The fisherwomen have received training on project development, environmental issues, and have gained knowledge from interacting with other women in Mexico and other countries.

In recent years, the cooperative has centered its efforts on environmental projects. These include monitoring water quality and contamination levels in mussels. Currently, the cooperative owns its own equipment and is awaiting approval for a new project to collaborate with the Chacahua National Park.

According to an article published by the United Nations, women are more likely to take action to restore ecosystems, as they are most affected by climate change. The Mangrove Fisherwomen Cooperative is a clear example of this.

The cooperative members are also working to open a canal that previously connected the Pastoría with the Palmarito lagoon. By doing so, they hope to increase the oxygen level, facilitate water exchange, and allow access to fisherwomen and men. “We can do the same tasks as a man. We have already proven it, with our work in the canal. There we work with shovels, and it is hard work. But we did it,” says Cirila Martínez.

A version of this article was previously published in Spanish in El País.

Natalia Torres Garzón graduated with an MSc in Globalisation and Development at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, UK. She is a freelance journalist who focuses on social and political issues in Latin America, especially in connection to Indigenous communities, women, and the environment.

With photographer Antonio Cascio, she founded the radio-photography program, Radio Rodando. Her work has been published in the section Planeta Futuro from El País, New Internationalist, Earth Island, Toward Freedom, and El Salto.