It has been a year and a half since Cuenca, the third largest city in Ecuador, voted to ban mining projects within the nearby watersheds. The historic referendum affected 43 concessions including the Loma Larga mega-mining project, which, if carried out, would have a dramatic impact on the páramo wetlands of Kimsacocha, an ecosystem that supplies water to numerous Indigenous, campesino, and urban communities in southern Ecuador. However, despite the fact that 81 percent of Cuenca’s electorate said “no” to mining, in July 2021 the conservative government of Guillermo Lasso transferred the Loma Larga project to Dundee Precious Metals, a Canadian company that already declared it will not respect the referendum results. Lasso also enacted decree 151, which seeks to expand mining exploration to 72 percent of the national territory. The decree is part of the government’s plan to aggressively expand the extractive frontier of oil and mining projects, all in the hope of generating revenues to alleviate Ecuador’s foreign debt and ongoing recession.

Confronted with the advance of the extractive frontier and a political, economic, and social crisis, different social movements joined Ecuador’s Indigenous organization, the Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE), in its call for a national strike on June 13, 2022. These movements include the Frente Nacional Anti-Minero, a recently founded national front of anti-mining resistance composed of 78 different organizations from across the country. A mining moratorium has not been part of the Indigenous Movement’s agenda in the past, as it was historically mobilized against neoliberal austerity. However, a call for a moratorium on mining was the fifth point on the list of political demands made to the government of Lasso in the recent strike. This inclusion is the product of a complicated history of alliances made between Indigenous, campesino, and urban organizations in the last two decades, which have given birth to a nation-wide movement of anti-mining resistance.

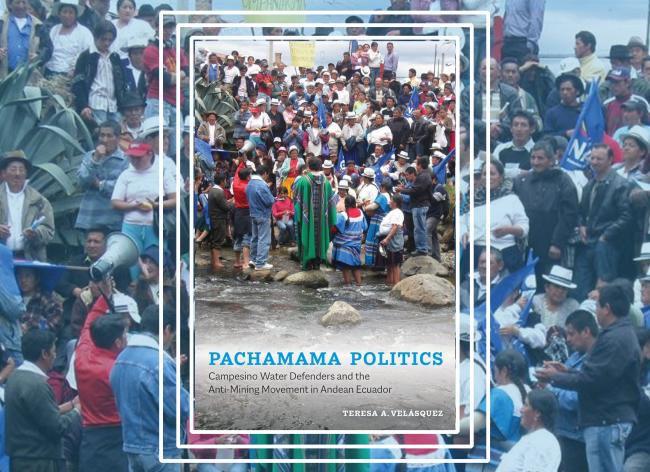

Teresa Velásquez’s book, Pachamama Politics: Campesino Water Defenders and the Anti-Mining Movement in Ecuador (2022), centers precisely on this historical development. By focusing on the politics—or what the author calls “Andean cosmopolitics”—of water defenders resisting mining activities in the Kimsacocha wetlands, Velásquez offers an exhaustive ethnographic analysis of how campesinos redefined their relationship to Indigeneity through anti-mining organizing. As Velásquez argues, campesinos in this part of the Andes had “little sustained participation” in the Indigenous movement throughout the 1990s. The state’s opening of large-scale mining projects in Indigenous and campesino territories, however, generated the conditions for campesinos to build unprecedented alliances with the Indigenous Movement and with urban organizations. While this alignment allowed water defenders to position their struggle nationally and to shape the lines of political confrontation around extractivism, it also transformed their self-identifications in unforeseeable ways.

The book covers a historical period that spans the neoliberal period (2005-2006) when reforms imposed by foreign capital expanded mineral extraction, the rise to power of the pink-tide government of Rafael Correa (2006-2017), the adoption of a new constitution that recognizes the Rights of Nature but also of controversial mining legislation (2008-2009), and concludes with the end of Correismo when the banker Guillermo Lasso won the presidential election of 2021. Each chapter takes us through Velásquez’s activist research in chronological fashion, as a way of narrating the political transformations of Indigeneity in the water defense movement. As the author makes clear throughout her carefully woven ethnography, these transformations should not be understood as a “straightforward story of how campesinos became Indigenous.” On the contrary, Indigeneity and what it means “to be Indigenous” are constantly challenged and redefined through the water defenders’ own voices.

Moving away from essentialist and culturalist approaches which fix Indigeneity in cultural traces like language, Velásquez adopts a political conceptualization of Indigeneity as a fluid, unstable category. According to this conceptualization, Indigeneity is a political project that challenges racist forms of mestizaje and that is repurposed in the anti-mining struggle to resist developmental extractivism. As the author illustrates in Chapter 5, this process has meant that some campesino water defenders reclaim an Indigenous identity as a “language of resistance” against mining projects. While the process of self-identification is not without contradictions and contestations—especially by campesina women who have refused to “play along,” given how certain practices of re-Indigenization position them as gendered “bearers of authenticity and tradition”—Velásquez shows how transformations of Indigeneity in anti-mining struggles are primarily about redefining activists’ relationship with their territories and with the state.

In fact, by following reconfigurations of Indigeneity in the anti-mining movement, Velásquez reveals where water defenders locate their main disagreement with the state: they dispute the “Quimsacocha” mine project as “Kimsacocha,” a “life-sustaining entity.” In other words, Indigeneity is mobilized as a language and practice that seeks to visibilize what campesinos defend is not a simple plot of land that contains minerals as resources, but rather a sacred and life-generating space. This recasting of “Quimsacocha” into “Kimsacocha” mobilizes an Andean cosmopolitics, a politics characterized by deep ontological disagreements about “what is at stake” in extractive conflicts.

The redefinition of Quimsacocha into Kimsacocha has also had the effect of redefining campesinos’ relationship to the state. By evoking the Rights of Pachamama (Mother Earth in Kichwa) and reproducing concrete practices like outdoor mass to defend the páramo wetlands as a sacred source of life, campesinos challenge prevailing forms of state- and elite-led mestizaje that have historically “prompted campesinos of Indigenous descent to shed external markers of Indigeneity.” These strategies necessarily challenge the state’s power to define what is Indigenous or not, at the same time that they dispute or reconfigure the tools provided by law and the state. This is the case of the constitutionally recognized Rights of Nature, which is redeployed as Rights of Pachamama, a language that conveys the understanding that there is much more than mere “nature” at stake; rather the places campesinos defend from mining extraction are living entities inhabited by human and more-than-human beings.

Overall, Teresa Velásquez's Pachamama Politics makes a significant contribution to our understanding of how Indigeneity is challenged, reconfigured, and mobilized in territorial struggles over natural resources. It is in the context of territorial struggles that extractivism and the spaces it threatens to occupy are redefined as well. Velásquez’s analysis goes beyond others that explain the proliferation of anti-extractive movements as a direct response or reaction to pink tide governments’ neo-extractive policies. By starting her study in the years prior to the presidency of Rafael Correa—that is, in a neoliberal period when the state granted an unprecedented number of mineral concessions into new watersheds and territories—the author shows how anti-mining organizing responds to global changes in regimes of capitalist accumulation that have massively expanded the extractive frontier. At the same time, the book’s chronological analysis illustrates the neoliberal continuities of the mining legislation of the Correa administration—continuities that have been repurposed by the current conservative government of Lasso to expand the mining frontier and intensify foreign-led mining projects.

Though Velásquez’s nuanced analysis is on full display in the ethnographic chapters, it is unfortunately not fully present in the Introduction and Conclusion. Resorting to a critique of the traditional Left represented by Correismo, Velásquez’s Epilogue calls for a political “third way,” embodied by the presidential candidacy of the Indigenous leader Yaku Pérez, which could “move away from the extractive model of development.” Yaku Pérez has been an important leader in the water defense movement, and while Correismo launched a racist campaign against his candidacy, Pérez’s presidential campaign mirrored the pitfalls of political discourses that portray Indigenous identity as an antidote to flawed (extractive) Left politics and also championed neoliberal proposals for “reducing the size of the state.” In my reading of the book, the author’s compelling ethnographic analysis is precisely what complicates this kind of deployment of Indigeneity, and what illustrates the potential of Indigenous politics in building multiethnic and multiclass alliances against contemporary forms of extractive capitalism and neoliberal austerity.

Andrea Sempértegui is an Assistant Professor of Politics at Whitman College and a member of the anti-extractive collective Comunálisis based in Quito, Ecuador.