This piece appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of NACLA's quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

On the morning of November 6, 1985, an M-19 guerrilla commando stormed the Palace of Justice in downtown Bogotá. Holding hostage more than 200 workers, judges, and visitors, they demanded that President Belisario Betancur face trial for violating a ceasefire agreement, among other infractions. The Army responded with unrestrained force, applying the protocols of a security doctrine, known as Plan Tricolor 83, that called for the enemy to be obliterated as fast as possible, with no negotiations. In a two-day military counter-siege, shelling and explosions completely destroyed the Palace of Justice. The numbers are not definitive, but between 91 and 115 people were killed, including all 30 or more M-19 members and 11 judges. Twelve cafeteria workers and one M-19 member were disappeared.

Although many journalists have tried to reconstruct the events through testimonies, documents, and military communications, there are no images of what happened inside the Palace of Justice or the adjacent Museum of Independence, which became a base of military operations during the siege. In 1986, a government-commissioned report denied the disappearance of persons. At the time, forced disappearance was not enshrined in Colombian law, which made the crime difficult to explain, understand, and denounce.

Over the next two decades, the relatives of the disappeared and multiple human rights lawyers and organizations demanded that state institutions provide a clear answer about the whereabouts of the disappeared. Their lawyer, Eduardo Umaña Mendoza, was murdered in the office of his Bogotá apartment in 1998, only a few months after the excavation of a mass grave in the city’s Cementerio del Sur. The first criminal investigation about the disappeared was opened only in 2005. The attorney in charge of the case gathered information that had previously been dismissed, hidden, or concealed—testimonies, videos, letters, and military documents—and was able to prosecute several military commanders.

In 2009, a Truth Commission on the Palace of Justice released another report, this time recognizing the disappearance of a number of people and the extrajudicial killing of others. Although finding a definitive truth about who shot, who killed, and when it occurred was tremendously important, the focus on the spectacularism of the battle obscured its surroundings. Most importantly, this limited approach severed the connection between the Palace, the city, and a larger context of counterinsurgent warfare.

A more recent project sought to shed light on these gaps, focusing on disappearances. In a collaborative project between Forensic Architecture and the Colombian Truth Commission—appointed as a result of the 2016 peace accords between the FARC and the government—I co-directed a transnational team that investigated the siege and its aftermath. The project is composed of three main films; a 3D physical model of the main square, the museum, and a key military complex where suspects were taken; multiple maps; a timeline of the violence against evidence; and archival material. The results were published in December 2021 as part of a larger exhibition called Huellas de Desaparición, which is considered an aspect of the Truth Commission’s results, preceding its 2022 final report.

This investigation is aimed at actively incorporating the practices of destruction, obfuscation, and denial of evidence as constitutive aspects of the execution and the persistence through time of forced disappearance. The project offers a way of understanding forced disappearance by moving away from the absences that usually lead to suspension and paralysis, instead returning to a focus on the material presences—that is, to the infrastructural arrangements of the built environment and the technical aspects of registering information that produce and sustain the crime of forced disappearance. In the events at the Palace of Justice, the Museum of Independence became a key node in this process.

The Palace of Justice is located in Bogotá’s main square, which, like in many Latin American cities, is surrounded by traditional institutions of power. Opposite the Palace, on the south side of the square, is the National Congress. To the west are the offices of the mayor of Bogotá, and to the east, the Primatial Cathedral. In the northeast corner, between the imposing buildings of the Cathedral and the Palace of Justice, a small colonial house hosts the Museum of Independence Casa del Florero, the “house of the flower vase,” named after a cornerstone in Colombian collective memory. According to the story, in the early 19th century, a group of conspiring Criollos planned a public skirmish in the main square. They asked a man called Llorente to lend them a flower vase for a dinner in honor of the royal commissioner. Llorente refused, and the Criollos made such a fuss about it that they sparked the revolt that led to independence in 1810.

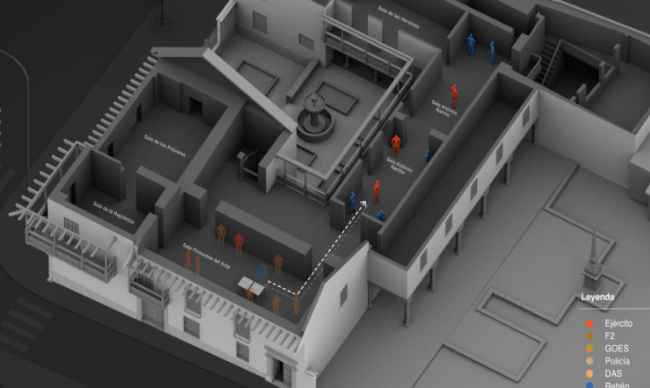

One hundred seventy-five years after independence, the Army took advantage of the museum’s strategic location to use it as a center for operations during the Palace siege. The museum’s rooms, stairs, lobbies, hallways, and gardens were resignified as spaces from which to organize the military deployment, manage and process counterintelligence information, secure the released hostages, and manage suspects. The military referred to the suspects as “specials,” set them apart, and defined them as potential subversive threats. Several people were tortured in the museum and taken to other facilities in the city. Some of them were eventually disappeared; others were shot and returned to the Palace.

In the previous years, the military created Plan Tricolor 83 as a set of guidelines to protect the nation from internal and external threats. It was activated on November 6, 1985 to defend the very notion of the nation in honor of which the museum was created. In that way, the museum became the underside of its very reason to exist, and it ended up representing the contradictory constitution of the Colombian state: on the one hand, the aspiration of democracy and modernity in the form of a republic, and on the other, the deployment of terror to secure that aspiration.

Presence as Absence

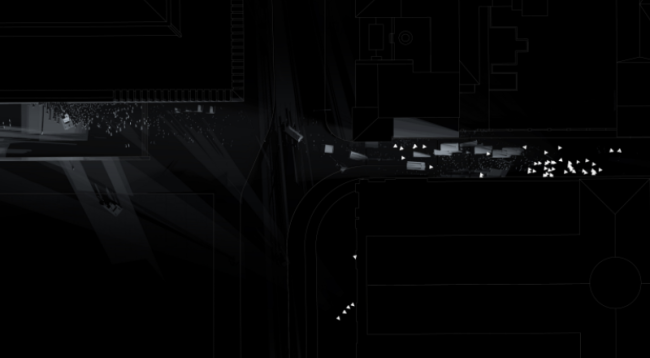

The persistence of forced disappearance is defined by the absence of the body. As a crime, disappearance is active until the remains of the person are found, bringing legal closure and clarity. During the search, the body emits signals—in the form of testimonies, images, and objects—of its presence that become sparks of light in a world defined by pitch-black darkness. The search for the disappeared, then, is a struggle to capture and connect these flashes of presence before the light fades into obscurity again. Often, these signals of presence are organized in a linear sequence of events. When the flashes of light cease to illuminate, a search reaches a moment of suspension— not an end, for there is movement in darkness.

Banu Bargu suggests that, as a political act, the violence of forced disappearance radiates outwards, beyond the immediate victim, to reach their organizations and intimate circles. In that sense, disappearance suspends life in time, expanding through the life networks of the disappeared and persisting as a continuum of uncertainty. Life ceases to move but does not extinguish. In contrast, clarification becomes linked to movement, for shedding light into the darkness of the crime allows for justice, resolution, and the possibility of moving on.

The obvious counterpoint of the body as absence is its presence. Often, the aim of disappearance as a suspension of life is achieved when the search reaches a wall, when all the possibilities of clarifying new information seem to have been explored and exhausted. But even then, there may be more search directions beyond the limits of what’s visible, residing in obscurity.

The term “negative space” describes the area that is around, within, and between objects. It provides a framework for analyzing a relation and interaction between material objects and the space in which they exist, between the material and the unseen. Rather than dismissing the space between objects, the idea of negative space is an invitation to consider the active role it plays in the organization of landscapes and places. In other words, the concept proposes an understanding of space as a relationship between material presences and absences, where the absence of objects coproduces shapes, volumes, and dimensions of landscapes.

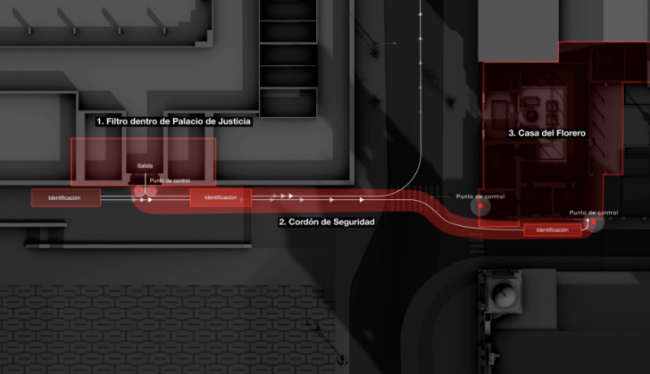

In our investigation of the disappearances at the Palace of Justice, we focused precisely on the relationship between objects such as buildings, vehicles, roads, and people. We paid attention not only to the interaction between these objects, but to the space between them, and the forms and effects that the negative space created, to understand two main dynamics. First, we sought to shed light on the logistical organization of the main square, the museum, and the city as a coordinated practice that made the disappearances possible. Second, we sought to make visible the creation of a material network that was deployed throughout the city in military facilities, hospitals, courtrooms, and archives, and that has sustained the uncertainty of forced disappearance up to the present. I will describe two aspects of this: the creation of a security corridor, and the role of the Museum Casa del Florero, which has been widely neglected in previous attempts to understand what happened in 1985.

Fragments and Chaos

In the hours after the M-19 members seized the Palace, multiple news crews recorded the unfolding events: tanks and soldiers storming into the building, rockets blasting the walls, a helicopter dropping a few soldiers on the rooftop of the Palace—a move so spectacular and pointless that it appeared to be inspired by a 1980s action film. The cameras also captured the fire and smoke that consumed everything inside, including the moments when hostages were released. The hostages rescued from the Palace were taken to the Museum Casa del Florero, located just meters away and separated by 7th Street, one of the most important thoroughfares of the city. In the video footage of the hostage transfer, several people who would later be disappeared were registered as alive.

Read the rest of this article, freely available online for a limited time.

Oscar Pedraza is an anthropologist and historian. He is an ACLS Fellow at the University of Southern California’s Center for Law, History and Culture, a research fellow at Forensic Architecture, and cofounder of Plano Negativo, a visual investigations and research collective focused in Colombia.