Sixty years ago, when Moscow and Washington reached an accord that resolved the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, the world breathed more easily. But for 4,100 of the 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban children who had arrived in Miami over the previous 22 months, and who were still scattered all over the United States, the future looked bleak. The prospect of reuniting with their families was more uncertain than ever.

Quaintly dubbed Operation Pedro (or Peter) Pan, the evacuation scheme for Cuban children had been initiated in the lead up to the fateful April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. Washington had hoped that by offering sanctuary for the offspring of anti-Castro activists, more Cubans would remain on the island and participate in what was expected to be the successful ouster of Fidel Castro and halt the rapidly accelerating revolutionary process.

What was behind this unprecedented mass exodus of Cuban children is still highly contested. In Cuba, even though no one was ever arrested or charged for having organized the evacuation scheme, the story is often recounted as one of a mass kidnapping of the nation’s smallest citizens. On the other hand, the story of Operation Pedro Pan has helped bolster Washington’s belligerent policy toward revolutionary Cuba for well over half a century.

The Hoax of “Patria Potestad”

When U.S. President Donald Trump announced in June 2017 that he was “canceling” his predecessor Barack Obama’s Cuba policy, he made special mention of the exodus as evidence of what he stressed was the “brutal nature of the Castro regime.” In doing so, he was simply reiterating what has become the orthodox view in the United States: that the operation was an urgent, humanitarian mission to save Cuban children from “communist indoctrination.”

The airlift was spurred by a widespread rumor that the government was about to promulgate a new law that would eliminate parental authority, or “patria potestad.” This hoax undoubtedly tapped fears, prejudices, and insecurities among largely white and more privileged Cubans in a highly volatile political climate. The introduction of daycare to encourage women to participate in the workforce and the revolutionary process, along with the desegregation, nationalization, and secularization of a previously highly discriminatory and corrupt education system, also alarmed more conservative sectors of Cuban society.

CIA psychological warfare operatives in Cuba went so far as to print and circulate a fake government “decree” outlining government plans to assume custody over its youngest citizens. Only decades later would some former agents such as Antonio Veciana express sincere regret for their part in perpetrating this fraud.

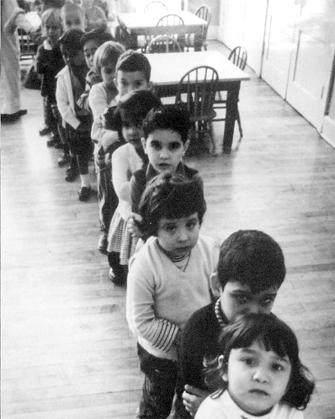

In the Cold War atmosphere, publicity about the plight of the little Cuban exiles fed U.S. propaganda against the revolution at home and abroad. A heart-wrenching documentary featuring a sad and lonely little boy was made and circulated by the U.S. Information Agency, and appeals for foster families published in U.S. newspapers stated bluntly: “We can think of few better ways to ‘fight communism’ than to care for the children who flee from it.”

The Pedro Pans were paraded as junior anti-communist celebrities at American Legion and Catholic Church functions to recount their horror stories of Castro’s Cuba, and their “rescuers” were hailed as heroes.

From “Rescue” to Isolation

The airlift was facilitated by an extraordinary, politically motivated, and unprecedented immigration policy. During the Trump years, the children of Central American and other migrant families were brutally torn from their parents’ arms in the name of a “zero-tolerance” policy toward undocumented entrants. In contrast, after the Cuban Revolution, Father (later Monsignor) Bryan Walsh, a young priest who ran a small staff at the Catholic Welfare Bureau in Miami, received the imprimatur of the State Department to sign visa waivers for as many Cuban children as their parents wanted to dispatch.

A federally funded foster-care program (the Cuban Children’s Program) was established, and within a few years it had become a major part of the federal government’s refugee budget. Far from being overcome by panic about the supposed threat to childrens’ minds and parental rights, some Cuban families saw this as an opportunity for a much coveted “beca” (or scholarship) for their offspring to study and learn English in the North, a factor that is frequently overlooked in accounts of the operation.

By October 1962, the child evacuation scheme had largely served its purpose in Washington’s covert and propaganda wars against the Cuban Revolution. The anti-Castro networks in Cuba on which the operation had relied were significantly weakened. More importantly, however, the airlift was no longer viable after the cancellation of direct flights between the United States and Cuba.

At this point, U.S. policy towards Cuba became isolationist, making emigration from the island more difficult and costly as Cubans had to travel through third countries. This significantly hindered the possibility of reuniting stranded children with their families. Furthermore, the number of children requiring placements was overwhelming foster-care agencies in Florida and elsewhere, and young Cubans arriving in Miami during 1962 were often more likely to find themselves sent to orphanages and other inappropriate placements if they could not be claimed by family or friends.

These policy changes highlighted the flawed justifications for the program: were the minds of children remaining in Cuba no longer in peril? Why stop the evacuation effort, even if it was more difficult at this time?

As former U.S. diplomat in Havana Wayne Smith acknowledged, “we now know, the rumors [about the ‘patria potestad’ law] were false. The children [who stayed in Cuba] were not separated from their families, and so the painful experience was not really necessary."

The Pedro Pan Generation Grows Up

What happened to those thousands of young Cubans who found themselves stranded by the momentous events of October 1962? Most, but not all, were reunited with their families when the so-called Freedom Flights from Cuba to the United States began in December 1965. However, several months later between 5 and 10 percent of the Pedro Pans had still not reunited with at least one parent. About 3 percent never reconnected with their families, and only a handful of them ever returned to live in Cuba.

When families did eventually reunite, in cities and towns across the country where the children had been sent, many found it impossible to take up where they had left off, especially those who had been separated for years. Thus, although the Pedro Pans were indeed “children who could fly like Peter Pan” in J.M. Barrie’s original children’s “fairy play,” the metaphor for the exodus proved tragically ironic. Unlike the storybook character who never grew up, many of the young Cubans soon found themselves alone in a foreign land and forced to grow up all too quickly.

Over the years, the story of the desperate flight of the Cuban children became key to the ideological foundation of the Cuban exile community. It continues to justify the political power and special privileges Cuban immigrants still expect and enjoy as “political” and not “economic” refugees. In fact, some Cuban Americans were recently enraged when Miami’s Archbishop Thomas Wenski dared to compare the unaccompanied children from Central America attempting to cross the border today with the flight of the Pedro Pans from “communist Cuba.”

One tragic ending is the paradoxical tale of Carlos Muñiz, who was assassinated at the age of 26 by the very same anti-Castro exiles who had supposedly rescued him as a Pedro Pan. Along with his mother and sister, Carlos settled in Puerto Rico, where he was influenced by the island’s independence movement. As a student, he joined a group of young Cuban Americans who sought a dialogue and reconciliation with the land of his birth. These young émigrés’ visits back to Cuba, however, provoked a violent reaction from the exile community. Although the exile terrorist organization Omega 7 claimed responsibility for the crime, no one was ever charged for Carlos’s cold-blooded murder.

“My mother took the decision to send me [out of the country],” commented Silvia Wilhelm, a former Pedro Pan, “but the decision to return was mine.” She felt a need to return “in order to close the circle and to make peace with ourselves, our history, and our country.” For many parents, however, such return visits challenged not only their painful decision to send their children out of the country alone but their very identity as an exile community.

One former Pedro Pan reflected in anger: “I began to feel part of a great hoax of an enormous manipulative machine…. What had happened is that the Americans were using the Cubans: [T]he departure of the children had been a propaganda tool. And what came out of the [Miami children’s] camps was a wounded generation.”

Many Cuban families remain split today—politically and geographically. Sixty years later, recalling the tragic tale of Operation Pedro Pan sheds light on how effectively natural family sentiments were manipulated by Cold War propaganda and how Cuban children became caught up in an international political power play. While little known among the wider population in the United States, the episode remains a touchstone in U.S.-Cuba relations and is still recalled with great bitterness on both sides of the Florida Straits.

Deborah Shnookal is a historian and editor, who has written and researched on Cuban history for 30 years. She is currently a research fellow at the Institute of Latin American Studies, La Trobe University (Australia). She is the author of Operation Pedro Pan and the Exodus of Cuba’s Children (University Press of Florida, 2020).