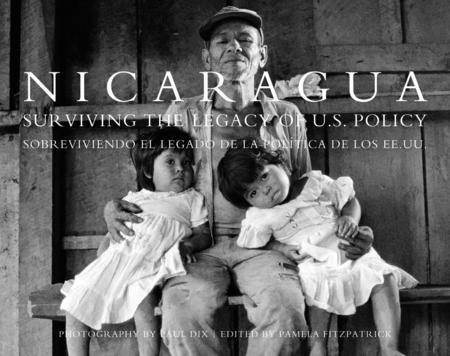

U.S. photographer Paul Dix and editor Pamela Fitzpatrick recently published the book, Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy of U.S. Policy. The book evokes the horrific legacy of the Contra war through individual testimonies of everyday Nicaraguans who survived the war that killed over 200,000 people over 20 years ago. In it, Dix revisits war survivors that he photographed in the 1980s and brings us up to date with their lives through a mixture of thought-provoking narratives and images. He adroitly slips between the past and the present, and juxtaposes moving and sometimes graphic images of the survivors as young men and women, and later as adults, with their unsettling testimonies of the war. In the process, Dix unflinchingly depicts the trauma that the Contra war wrought in the lives of so many Nicaraguans, and the continuing legacy of U.S. policy in the region. Photojournalist Paul Jeffrey reviewed the book in the latest NACLA Report. The following collection of photos from the book were all taken by Dix.

Jamileth Chavarría in 1987 as she leaned on a cross at the burial site of her mother, who was killed by the Contras on the muddy road into the remote jungle outpost of Bocana de Paiwas. Chavarría went on to become an outspoken critic of U.S. involvement in Nicaragua.

Jamileth Chavarría in a women’s radio station in Paiwas in 2002. In her testimony, Chavarría reflected a sentiment commonly held among Nicaragua’s poor: Although she knows who in the Contras killed her mother in 1987, she doesn’t hate them. Instead, she blames, "the gringos [who] were the ones that made Nicaragua divide itself. . . . The gringos were behind all of this, and . . . the Contras were also victims of the gringos.”

Graciela Morales, 18, holding a flag at the sixth anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution’s victory in Managua in 1985. At age 14, Morales fought alongside the Sandinista forces against the Contras.

Graciela Morales in Costa Rica, in 2007. She recalled the benefits the revolution brought to her—a girl from a poor family—enabling her to go to medical school to become a physician. Had there been no revolution, she said, “I would now be a peasant myself, perhaps the mother of five or six little kids, working in the field with my husband.”

Carmen Marina Picado Aldana, 19, lies mute in a hospital bed in 1986. Her missing legs are testimony to the terror of a Contra mine that killed six and wounded 43 along a road north of the city of Jinotega.

Dix stayed in contact with Carmen Marina Picado Aldana and, in 2004, photographed her again, this time walking with crutches along a Matagalpa street with her two children. In describing her situation, Dix notes that she survives “with no visible means of support.”

As a victim of the Contra war, Carmen Marina Picado Aldana struggles every day to cope with the physical and emotional scars of war. She confesses that her physical challenges are at times overwhelming. “One moment I feel calm,” she says, “then I feel like something hits me in the heart, and I’m overcome with desperation, and I cry and cry and cry.”

Coni Pérez, 6, swings upside down from a hammock in her home in the small village of Lagartillo in 1988, which was targeted by the Contras in 1984, on New Year's Eve Day. Fourteen years later, she commented on the irony of U.S. policy abroad. “It is terrible to think that in a country like the United States, for example, the young people who live there don’t know anything about what their own country does in other countries,” she said.

Tomás Alvarado leads a pro-Sandinista march from the Honduran border to Managua in 1990.

Tomás Alvarado, who was injured fighting against the Contras in 1984, plays basketball with friends in 2002. An activist for the rights of the disabled, he talks openly about how things have changed since the Sandinistas lost in the 1990 election. He tries to think positively to avoid succumbing to depression that can so easily envelope the lives of victims of the Contra war. “What is left for you to do,” he said, “is turn the chair around and think about how to move forward, first how to get out of bed, then how to leave the house, then how to go out into the street, and then how to work.”

A 1987 childhood drawing by Baltazazra Pérez Osorio, then 13, depicting two 14-year old boys surrounded by stones and defending the small village of Lagartillo from the Contras. The boys, inseperable friends who loved to play guitar together, died defending the village from the Contras on New Year's Eve in 1984.

Photographer Paul Dix is a freelance photographer documenting social justice and U.S. foreign policy issues. He divides his time between Oregon and Montana. Pamela Fitzpatrick has worked as a teacher and director of the Women, Infants, & Children Nutrition Program (WIC). She resides in Oregon and Montana. For more about the book, Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy of U.S. Policy, visit the website, nicaraguaphototestimony.org. Some of the caption text was taken from Paul Jeffrey's review of the book. To read the full review see the September/October 2011 NACLA Report, "The Politics of Human Rights."