“Wayrawasinchik kunanqa Llaqtapa sunqunpi,” chimes a pre-recorded announcement on Radio Inti Raymi during a sports broadcast from a local women's soccer match in the Apurímac region of Peru’s Andean highlands. “Now our radio station is in the heart of the town.” Then, over the shouts of both teams' fans at the game, the loud voice of the commentator cuts through the air. “Ayayayayyy our sister Lizbeth resists and then kicks the leather ball with all of her energies!” he narrates, speaking entirely in Quechua. “Now the leather ball is in control of the opponent team. Our sister Martha had thief-like feet with her ability to recover the ball.”*

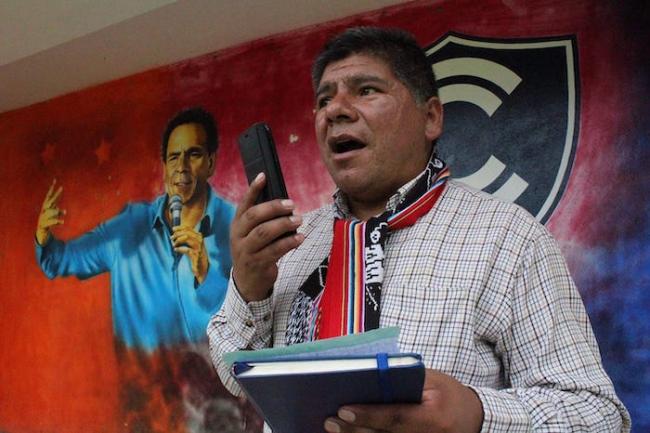

Quechua broadcaster Luis Alberto Soto Colque, better known by his nickname Qara Q’ompo, Quechua for leather ball, never fails to capture the emotion of the game. Throughout the match, he uses different Quechua phrases related to the local culture, which not only makes the commentary more exciting and engaging for his listeners, but also brings visibility to a new and rich vocabulary tailored to narrate soccer matches. In doing so, he contributes to expanding the Indigenous language into domains, such as sports, that in Peru historically have been exclusively Spanish-speaking.

While the women play soccer, Qara Q’ompo plays with his voice, using intonation and accent based on the Quechua knowledge of misk’i Rimay (sweet speech) and willarikuy (news). Both rimay and willarikuy were put into practice on the radio beginning in the early 1950s, when Quechua Indigenous voices began emerging on the airwaves in the Andean region of Cusco, interrupting the Spanish-language domination of early radio. However, in the last three decades, broadcasters like Qara Q’ompo have created a particular way of performing rimay and willarikuy in the narration of soccer matches throughout the Andes. At the same time, they have also continued to expand their reach, using new media to spread the Indigenous knowledge and language through the internet.

In 2016, Qara Q’ompo arrived in Challhuahuacho, a town in the Andean region of Apurímac, to narrate the final match of a local soccer tournament. I was working in that town as a local journalist, and a colleague of mine interviewed Qara Q’ompo about his work narrating soccer in Quechua. I was curious about his nickname because it reminded me of the old leather soccer balls that we used when I was in elementary school. In the pronunciation of both words, we use the aspirated and glottalized sounds that characterize the Cusco Collao variant of the Quechua language.

From the beginning of the interview, Qara Q’ompo exuded his radio personality as a Quechua sports journalist. His voice was characterized by an intonation that reaches the hearts of Quechua speakers. At times, he narrated using Indigenous knowledge by comparing the soccer players to uywas (animals cared for by humans) following the Quechua storytelling tradition. At other times, he connected the energy of the players to powers imbued by Andean agricultural products such as quinoa and maca. This way of communicating was familiar to Quechuas and attracted the audience’s attention.

Today, Qara Q’ompo uses not only radio but also social media to spread his voice, narrating soccer matches as well as local stories, horse races, Quechua communities’ anniversaries, parades, and other celebrations. His sports journalism and the emergence of Quechua journalists and commentators on the airwaves more broadly is the result of more than seven decades of Quechua broadcasting in Peru’s Andes.

Qara Q’ompo is from Qosqo, known today as Cusco, in the Southern Andes. According to Cusqueños, Qosqo means “the center of the world,” and Quechuas proudly identify it as the capital of Inca territory, known as Tawantinsuyu. The first radio station in Cusco was Radio Cuzco, which was inaugurated in 1937. According to the Cusqueños Jaime Alberto Cutire Arce and Javier Quispe Yupayccana, the first sounds on the airwaves were foreign Spanish music genres such as pasodoble, flamenco, and zarzuela. According to Luis Angel Aragón, Teófilo Guaylupo, the city priest, was the first person who used the radio to speak and spread his message into the ether.

At that time, the radio in Cusco was conceived as a new tool to expand the progress and modernity heralded by continued colonization and Indigenous erasure. However, the inauguration of Radio Rural in 1948 opened new opportunities to broadcast programs aimed at campesinos or Indigenous people. This new station gave space not only to the Quechua music but also to Indigenous voices, becoming the first space for Quechua radio locutores. In the ensuring years, radio became a prime way to spread their long-silenced voices.

The Making of a Quechua Sports Commentator

Five years after meeting Qara Q’ompo in Challhuahuacho, I again found myself in front of the major Quechua broadcasting figure. But this time we met virtually. In October 2021, we held a virtual tinkuy or meeting to talk about Quechua voices in radio throughout the Southern Peruvian Andes, and many attendees were eager to hear about Qara Q'ompo's experience because he is considered an umalliq or leader for the Quechua. He began the conversation with a greeting, as Quechua people do: Waliqllachu khumpaykuna, panaykuna, wawqiykuna. Apunchikkuna, inti tayta mama killa munayninwanmi kaypiqa tarikushanchis (How are you my brothers and sisters. Thanks to our sacred mountains, to our father the sun, to our mother the moon we are here together). A charismatic speaker, he is a Quechua harawiku, like the poets or speakers during the time of the Inca.

Qara Q’ompo explained that he didn’t set out to become an example and advocate of Indigenous voices on the airwaves. “It was in 2003 that the city's soccer team, Club de Fútbol Cienciano, won the Copa Sudamericana,” he explained. “Radio Mundo invited me to narrate the final match between Cienciano and River Plate from Argentina. I started narrating only in Spanish but when Cienciano won that match my heart could not express it in Spanish.”

It was a turning point—and a challenge. “At that moment, I decided to start narrating in Quechua, but I had difficulties because it was the first time that I had narrated in Quechua,” he continued. “Quechua is so sweet and vivid for us, but there is the limitation that we didn't have room for football narration in our language.” He began by preparing his own Quechua vocabulary to avoid the use of words borrowed from Spanish. Starting down this path also meant challenging the dominant style of broadcasting that narrates sports only in Spanish. This Spanish dominance is reinforced not only in mainstream media in the Andes, which prefer to use only Spanish, but also by journalism schools that avoid the use of the Quechua language, even though they have Indigenous journalists. Qara Q'ompo’s decision meant breaking that stigma and starting to use his mother tongue.

Taking on a project with such big challenges took time. Though spurred by his initiative, the effort also grew from collaborative work with the Quechua-speaking community. Quechua knowledge is not written, it is in the people, in the community, in the territory. In this sense, Qara Q'ompo had to collect Indigenous language knowledge from community members to develop his narration of the sport. “I started by asking our elders in different towns how I can say ball, soccer, throw, and everything related to a soccer match,” he explained. “With their help I created a vocabulary entirely in Quechua.” He visited communities such as Quispicanchi, Canchis, Chumbivilcas, Urubamba, and neighboring towns and villages, gathering a new vocabulary: for the ball qara q’ompo, for soccer qara q’ompo hayt’ay, for throw patamanta urqumuy, for corner kicks is k’uchuchamanta hayt’ay, for headers umachankuwan p’anay, for yellow card q’illu rap’i, and so on. “I found a rich vocabulary for soccer in Quechua that is associated with our passion for this sport and our Indigenous knowledge.”

Then Qara Q’ompo asked the directors of the Cienciano soccer team to be allowed to have access to the stadium when the team was playing. With that access he could narrate the matches directly in Quechua. “I showed them that I was well prepared to narrate in Quechua. They accepted my proposal, and I began to narrate live matches from Cienciano,” he said. There, he was able to perfect his know-how of narration in the Indigenous language. In 2003, Qara Q'ompo became the voice of the Quechua people when narrating the soccer games of the local club. Since then, his words have spread through the airwaves—and now on social media—during each Cienciano match.

Now, Qara Q’ompo urges Quechua journalists and locutores to use the Indigenous language and contribute to its revitalization. “We are together in this meeting thanks to our father the sun and our mother the moon. In that sense we must spread our language more,” he said during the virtual event. The internet, he added, is a valuable tool for preserving, spreading, and digitizing the language, but the work still lies with the speakers themselves. “Some of us are elders and others are part of the new generations, but we have the responsibility to spread Quechua language.” It’s a message he hopes will resonate with younger of Quechuas and that they will answer his call to action by using different spaces and media technologies to bring the language greater visibility. Quechua is a language in active use, and it needs more spaces to be maintained and passed on to new generations. Alternative media are a valuable public space to do just that.

At the end of our virtual tinkuy, Qara Q’ompo invited Quechuas to speak their language throughout the different activities of their daily lives. With this call, he challenges Quechua speakers to ignore stigma and forget the stereotype that the language belongs only in agricultural activities or in the past. “The digitization of the Quechua language is in your hands,” he emphasized. “We must globalize our language in the different activities that we do—in the economy, journalism, health services, education, and so on.”

Quechua has been an official language of Peru, alongside Spanish, since 1975. Currently more than 10 million people speak this language across the countries that make up the Andes. However, this does not mean that public services are offered in the Indigenous language. As Qara Q’ompo stressed, the use and future of a language depends not only on the actions of governments, but most importantly on those who insist on continuing to speak it.

*From the original Quechua: “Ayayayayyy pananchis Lizbeth sayapakamun hinaspa hayt’an tukuy kallpanwan qara q’ompota. Kunantaq contranpi kaqkunañataq bolawan kachkanku. Sumaq suwa chakichallaña pananchanchis Martaqa kasqa.”

Jermani Ojeda Ludena is a Quechua scholar from the region of Apurimac, Peru. Currently he is a doctoral student specialized in Native American and Indigenous Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. In 2021 he worked with major Quechua broadcasting figures through a project funded by the Alumni Network of the United States Embassy of Peru. The project aims to recognize Quechua broadcasters’ contribution to language revitalization.