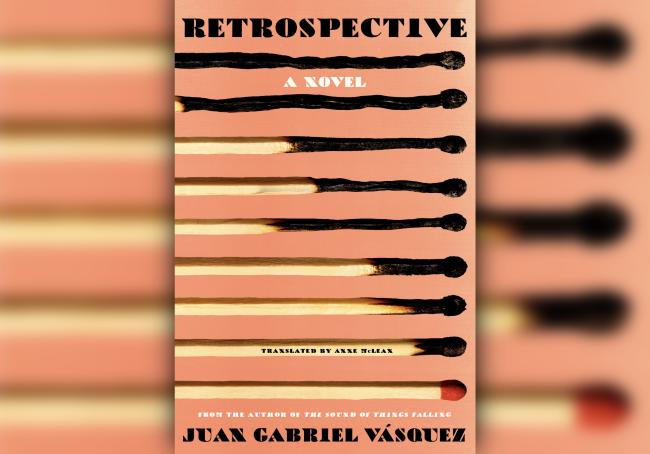

The Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez regularly examines his country’s turbulent political past and present. His novel The Informers (2011) explored the internment of German Colombians during the Second World War, and The Shape of the Ruins (2018) studied the political antecedents and consequences of the bogotazo—the mass demonstration and anarchy that took place in the Colombian capital on April 9, 1948. In his latest novel, Retrospective (translated by Anne McLean) Vásquez lightly fictionalizes the life and family history of Sergio Cabrera, one of Colombia’s most important film directors and a former guerrilla fighter.

The novel opens in October 2016, just after Colombia voted against the government’s proposed peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Sergio (as he is referred to in the text) had been a member of another rebel group, The Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and has recently attended a retrospective of his films in Barcelona. He has just learned that his father—once an important figure in the EPL—has died.

Vásquez then recounts how Sergio’s father Fausto, a Marxist theater director and actor, came to Colombia in 1945 after fleeing Franco’s Spain. Through local Maoists, Fausto developed ties to communist China and in 1961 he moved his family—his Colombian wife Luz Elena and their children Marianella and Sergio—to Beijing. Once there, Fausto and Luz Elena taught Spanish language classes to university and high school students, and prepared for a Maoist revolt in Colombia. Sergio, 11, entered high school and, alongside aspiring to a career in filmmaking, became a devoted revolutionary.

Sergio’s faith in socialism persisted during his adolescence despite encountering a doctrinaire Maoist environment whose rigidity affected him personally. For example, he was pressured into turning his back on a Yugoslavian girl he liked because the Chinese thought Yugoslavians were “bad socialists and accomplices to capitalism… a poisonous enemy.” Sergio completed high school in Beijing and won the respect of his peers after working on a commune. Vásquez explains that “The communes were the heart and soul of Comrade Mao’s vision of communist China. They were immense collective farms, places so enormous they were organized like small countries… [The workers’] fingers froze and they had to wash their hands with warm water in a special sink so their skin didn’t crack from the cold or their hands get so numb they wouldn’t work, but Sergio had never felt so useful.”

Sergio spent seven years in China trying to “build socialism,” but after Fausto became an important figure in the EPL, a Colombian Maoist guerrilla group, Sergio returned to Colombia in 1968 to participate in the armed struggle. On his way back, Sergio, 18, had a stopover in Paris. In a moment that encapsulates the young man’s political dilemma and the difficulty of processing his experiences, French leftists asked:

‘Is it true they [the Chinese] are breaking with the feudal past, with thousands of years of history? Is it true that can be done?’ Sergio thought about the men and women humiliated in public, heads bowed, meter-high hats accusing their wearers of complicity with capitalism, signs hanging from their necks with other charges in large characters—despots, landowners, enemy sympathizers, elements of counterrevolutionary gangs—and remembered the museums and temples ransacked by the violent crowds and the news of executions in the countryside, which only very few ever found out about. He remembered all that and felt for mysterious reasons that he could not talk about anything, or that they wouldn’t understand if he told them what he knew. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘It’s true. It can be done.’

In the EPL, Sergio took the nome de guerre “Raúl” and became ashamed of the “bourgeois preoccupations” of his artistic ambitions. The jungle, however, proved less satisfying than the Chinese communes, and Sergio “never freed himself of the nagging certainty that he had something to prove, and that his comrades looked at him warily, as if he wasn’t entirely one of them.”

The EPL was also full of sectarianism and interpersonal rivalries. Sergio’s sister Marianella was subjected to a guerrilla court martial, accused “of disrespecting the figure of Mao, of ideological deviation, of rejecting the armed struggle, of being against China, and therefore, of being pro-Soviet, Stalinist.”

Many times, Sergio pondered his future: “Was desertion—the most terrible crime a guerrilla fighter could commit—possible? No, it was not possible, and now Raúl felt that… his conscience committed a terrible crime against the revolution, against everything he had pursued for years and all that his parents had pursued.”

The doubts persisted, and although Sergio remained committed to leftist ideas, his reservations about Maoism and the armed struggle became insurmountable. On a damp morning in November 1971, after nearly four years with the EPL and despite the “nostalgia for what he would leave behind in the jungle, all the dreams, all the emotions, all the great projects he had once had, all the hopes he had brought back from his years in China,” Sergio handed in his rifle.

To focus on Cabrera’s political experiences, Vásquez largely omits the next 25 years of the protagonist’s life. During this time, Cabrera returned to China for college, then went to film school in London. In 1976 he began his career in Colombia, producing and directing films and television series of great variety. His series Escalona (1991), about the early life of vallenato singer Rafael Escalona, propelled the music career of Carlos Vives; La Estrategia del Caracol (The Strategy of the Snail, 1993) which describes a group of tenants in Bogotá fighting eviction, is a touchstone of Colombian cinema. His films have won numerous prizes and international recognition, including the retrospective in Barcelona that opens the novel.

Cabrera’s work often examines socialism and the Colombian conflict, perhaps most famously in Golpe de Estadio (Time Out, 1998), a satire in which the police and a guerrilla group agree to a ceasefire in order to watch the decisive qualifier for the 1994 FIFA World Cup. While Cabrera was filming Golpe de Estadio, the narco and guerrilla threat to the Colombian state was inescapable. Friends persuaded him to choose politics over art, and he successfully ran for a seat in the House of Representatives, where he served from 1999 to 2002.

Retrospective is written with rich detail and in Vásquez’s characteristically unpretentious style, but with a typically complex narrative structure that pushes the reader forwards and backwards in time. Despite Sergio’s remarkable story, at times—especially in the second half depicting his high school years in China—the scenes can be repetitive and the pace slow. The best and most dramatic section of the novel concerns the 2016 peace referendum in Colombia. Sergio watches the results come in with Golpe de Estadio and La Estrategia del Caracol actor Humberto Dorado. “The television showed ominous images of the Caribbean coast,” writes Vásquez, “where a hurricane had prevented hundreds of thousands of citizens from getting out to vote…The Bogotá sky grew prematurely dark and the phones began to buzz as messages arrived from all over the place. At one point Humberto Dorado, whose sweet nature was legendary, threw the remote control and said to no one: ‘What a fucked-up world.’”

In a postscript, Vásquez explains that his intention was not just to tell Cabrera’s life, but to give it “an order that went beyond a biographical recounting: an order capable of suggesting or revealing meanings not visible in a simple inventory of events.” Vásquez adds that “Retrospective is a work of fiction, but there are no imaginary episodes in it.” He includes real photographs, as he does in The Shape of the Ruins, and works tightly with oral history, as in The Informers. Vásquez spoke with Cabrera for more than thirty hours of recorded conversations, and exchanged vast correspondence with Cabrera, his wife, and his sister Marianella. Given its faithfulness to Cabrera’s life, Retrospective, which is told principally from Sergio’s point of view but also from Fausto’s and Marianella’s, could be described as both a novel and a biography.

In a recent interview with El Periódico de España, Cabrera said he was initially skeptical about Vásquez’s idea because he feared his family would look like “old guerrilla fanatics.” He was convinced by the author’s openness and dedication, and because he believed it was “important to show that it is possible to adapt to change while still working for your ideas.”

In 2022, over half a century after leaving Beijing to join the EPL, Sergio Cabrera returned to China after being named by a former congressional colleague, President Gustavo Petro, as the Colombian Ambassador. Once again, he is postponing his creative projects for politics.

Daniel Rey is a British-Colombian writer and historian.