Bolivia’s de facto president Jeanine Añez had only been in office for three days when troops under her command opened fire on a protest march near Cochabamba. It was November 15, 2019. The soldiers killed 10 unarmed citizens, wounded dozens more, and seized and imprisoned many of the march’s leaders. The protest had been called in support of Evo Morales, the Indigenous president who had been pressured to resign a few days earlier. Facing widespread protests in the wake of a contested election, Morales stepped down after the police mutinied, refusing to keep order, and the military high command went on national TV to suggest he resign. Morales and his vice-president fled first to Mexico and then to Argentina.

With the presidency and vice-presidency vacant, others from Morales’s party who were in the line of succession were also threatened with violence and resigned. Through a series of machinations planned by the main opposition parties—and backed by the EU, the Catholic Church, Brazil, and likely the United States—Añez named herself president under dubious legal circumstances. A group of military commanders in camouflage fatigues placed the presidential sash on her. The new president and her cabinet quickly signed a license-to-kill decree granting the military the task of “protecting the Bolivian people” and achieving the “pacification” of the country through all “available means” while “exempting them from any penal responsibility.” Then followed the massacre at Sacaba. Four days later the soldiers opened fire again, this time in El Alto, just outside of La Paz. They killed 11 more people, all of them unarmed. What followed was a year of violent repression and rampant corruption, as the country was hit both by Covid-19 and a kleptocratic regime. When elections were finally held again in October of 2020, Evo Morales’s party, the MAS (Movement to Socialism) returned to power, this time with Luís Arce Catacora as president. Morales triumphantly returned from exile in Argentina. Unlike many of her ministers, de facto president Añez did not leave the country fast enough. She was quickly detained and imprisoned, and is currently on trial along with several military officers. The country is now grappling with demands for justice, efforts to restore economic stability, and ongoing right-wing efforts to destabilize the government.

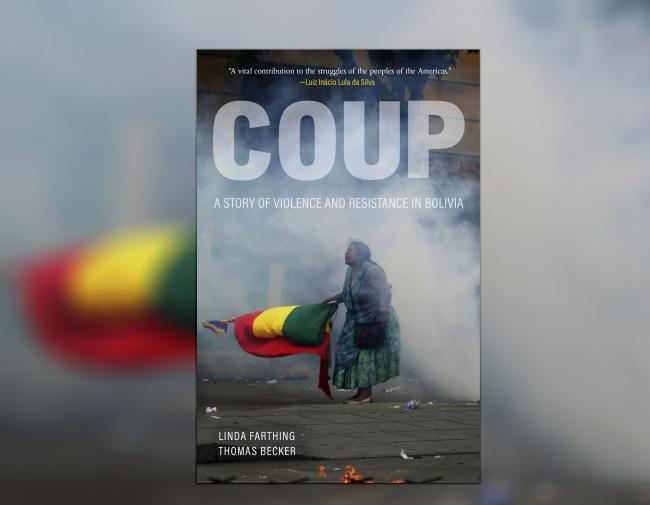

Most experts refer to the events that led to Morales’ ouster and Añez’s accession to the presidency as a coup. Linda Farthing and Thomas Becker make this argument as well in Coup: A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia. Farthing has been researching and writing on Bolivia for decades and was in Bolivia during the events of 2019. The book draws on her own first-hand reporting. Becker, a human rights lawyer, has been long involved in the country as well. Most notably, he is one of the lawyers representing family members of victims of tragically similar massacres carried out by the government of Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada in 2003. He was also in Bolivia during many of the events of 2019. In Coup, Farthing and Becker offer both a recent political history of Bolivia and a richly reported account of the events of 2019 and 2020. The book is a must-read for anybody who wants a deeper understanding of the events and the complex forces at play. The book is also an important historical document of this moment of crisis, narrated through the voices of hundreds of Bolivians interviewed by the authors. As the book’s title makes clear, the authors are unequivocal: the tumult that led to Añez occupying the presidency was “an illegal seizure of power,” in other words, a coup.

Despite their clarity in defining the events as an illegal takeover, the authors do not shy away from pointing out the errors and flaws of the MAS government and of its charismatic leader Evo Morales. Central to the debate here are the contested elections that paved the way for the coup itself. A month before the coup, in October of 2019, Evo Morales was running for re-election. It would have been his third term (or fourth, if you count the term he served before the new constitution went into effect in 2009). That constitution had enshrined a two-term limit—a point demanded by the right-wing and conceded to by the MAS to get the constitution approved. So the idea that Evo Morales would run again was opposed by many. Morales tried to roll back term limits through a national referendum In 2016. He narrowly lost that vote (49 percent to 51 percent). Unsatisfied with the result and confident of his right to run, Morales sued, arguing that term limits were in fact unconstitutional. The constitutional court eventually agreed, overturning the results of the referendum. Fast forward to 2019: in the months prior to the election, a fair segment of Bolivia, particularly the urban middle-classes, had already decided Evo’s candidacy was illegal and the election itself would be a fraud. The die was cast for a coup foretold.

While the authors are critical of Evo’s decision to run again, they do not espouse the narrative that would later emerge, that the elections were fraudulent. Experts continue to debate whether or not the evidence for widespread fraud exists (for the record, I do not believe it does). But at any rate, the split in Bolivia is now between those who call it a “coup” and those who say it was “fraud.” Those on the latter side of this split will not appreciate the nuance that Farthing and Becker try to show with their critique of Evo. In fact, they will likely start with quibbles about the title itself, since in their minds, there was no coup, only a fraud. If any such reader gets past the title, they will be treated to a litany of evidence that lays out a strong case that it was indeed a coup. On the question of fraud, the evidence is just not there.

On the other hand, those sympathetic to Evo might find some of the book’s critiques of what the authors call his “flaws” unfair. Yet there were many. Despite being a darling of the international Left, Evo Morales and the MAS government had shifted to the right. For pragmatic reasons, they pulled back from many of their more ambitious reforms, particularly in land reform and Indigenous rights. The MAS made deals and concessions with the agroindustry, a bastion of right-wing opposition. It had stumbled often, most notably in promoting large-scale development projects, like one highway project through the Amazon lowlands that resulted in police repression against Indigenous opponents in 2011. Questions of the burning of the rainforest, the quashing of any progressive sexual rights platform, and the failure to act on the epidemic of violence against women were all fodder for critics of Evo, and points included by the authors here.

The Introduction does a good job of summarizing this history, as does Chapter One, which seems to suggest that Evo was at least in part to blame for the “overconfidence and triumphalism” that led him and the MAS to seek one more term in office. The authors suggest that had Morales not tried to abolish term limits—first through the 2016 referendum, and then through the supreme constitutional court maneuver—the coup might not have happened. Along with this “mistake,” they argue that the MAS was at once overconfident in its own power and naïve in its estimation of the hostility of various forces who played a role in toppling them – the right-wing elite, Brazil, the European Union and the United States, the Organization of American States (OAS), and ultimately the Bolivian military itself. Here, to be sure, they are right.

Those more sympathetic to Morales and the MAS might disagree with what seems a bit of a “blame the victim” story. Morales does have a well-deserved reputation as a historic leader resistant to U.S. imperialism. But at times, his charismatic appeal and his Indigenous identity have given observers a bit too much romanticism. The authors are right to point out these mistakes and political miscalculations. It is important to recognize errors and push thinkers on the left to reconsider what precisely counts for left or progressive policy and when it is worth negotiating away hard fought social and political gains. To their credit, the authors also spend many pages recounting the many progressive gains of the MAS in economic and social terms. These “accomplishments,” they write, “[should cause us to] salute the enormous effort made by Bolivians, from social movements to government bureaucrats to MAS party militants, who collectively worked without pause to bring a different vision to life.”

No book will please everyone. Those on the left who are less enamored of Evo Morales might find the authors’ treatment too generous. For some, the MAS government had become much of what it proclaimed to resist: a patriarchal behemoth that had entrenched itself in a state built on coloniality, racism, and violence. That is not the story told by Farthing and Becker. As the subtitle suggests, this is a story of heroic resistance to right-wing violence and imperialist intervention.

The chapters in parts two and three delve further into the various events—many of them criminal—that characterized the coup regime. With gut-wrenching testimonies from eye-witness accounts, the reader returns to Sacaba and El Alto, where military men fired at will, killing marchers as well as bystanders. “They shot us like dogs,” said one victim. Another said the soldiers cursed them as “Indians” who had no business coming to the city. The accounts offer a new understanding of the military’s role in the coup and its aftermath. Witnesses reported soldiers picking up empty bullet casings to try to hide evidence. Tanks used water cannons to wash blood away from the streets. Soldiers even attacked Bolivians who were trying to help the wounded. One victim was 24 year old Yosimar Choque Flores, shot in the arm while trying to help drag other wounded people to safety. The coup regime later claimed, ad nauseum, that the marchers had somehow shot themselves. In the end, it was once again the sacrifice of poor and working class Bolivians, most of them Indigenous, that paved the way for political negotiations. After the killing, the Añez government negotiated a pact with the MAS. If the blockades and marches ended, the coup regime would call for elections, but without the participation of Morales and former vice-president García Linera. It would take more marches and protests, but in the end, the Bolivian people and democracy prevailed. Tragically, much of Bolivia’s history similarly rests on the heroic bodies of dead Indigenous people.

Narrated with the keen eye for fact and detail of both a journalist and a lawyer, Coup is a page-turner that will enthrall anyone interested in the recent history of Latin America, and Bolivia in particular. And for a world that seems to be increasingly marked with right-wing efforts to declare fraud, undermine elections, traffic in fake news and plot coups, the book offers a scary warning about what lies ahead. Perhaps we can learn from Bolivians how best to resist.

Bret Gustafson teaches anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis and is a member of NACLA’s editorial board. He is also the author of Bolivia in the Age of Gas (Duke 2020).