In June, the Estado Mayor Central (EMC) issued an ultimatum to demobilized FARC combatants, or peace signatories, in southern Colombia’s Caguán region, demanding they vacate their residences within 40 days. The EMC, a dissident FARC group, accused the signatories of being accomplices to the Second Marquetalia, a rival dissident faction. The deadline to leave was July 25. Now, 40 former FARC combatants and their families have permanently evacuated the Miravalle reintegration camp.

“We are in an incredibly tough situation,” Miravalle resident Adriana Villa, a mother of three, entrepreneur, and former guerrilla fighter, tells me. “There are so many things that weigh heavily on the heart (oprimen el corazón), especially as we watch our home and dreams slip away. The change is particularly hard on the children.” The threats are alarming: the EMC is reportedly responsible for many of the over 400 killings of peace signatories since the 2016 peace accords.

The demobilized FARC personnel and their families fleeing Miravalle are not only abandoning their homes but also putting their peacebuilding ventures at risk. These efforts, including gourmet coffee production, fish farming, and ecotourism projects, were slated to become the families’ primary source of income when state subsidies for peace signatories end in 2026, in compliance with the 2016 accords.

Like the other 23 reintegration camps set up as part of the peace agreement, officially called Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces (ETCRs), Miravalle was intended to house demobilized FARC fighters for just two years. However, the state’s failure to fully implement the peace accord compelled them to remain indefinitely, further entrenching their roots in the region. Many of their peacebuilding ventures, like rafting on the Pato River and a locally run museum of leftist uprisings, have an intrinsic link to the region’s history.

My fieldwork in the Caguán region has revealed that the ongoing geostrategic disputes among splinter groups are deeply intertwined with the area's symbolic and historic heritage. This heritage is vividly articulated through the entrepreneurial endeavors of former FARC combatants as part of their reintegration process, and it plays a crucial part in ongoing disputes over the territory’s legacy.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, local media extensively covered the hostilities between the FARC and the Colombian Army in Caguán. Specifically, the Pato River valley was a significant flashpoint. The region became deeply ingrained in collective memory, particularly due to the failure of peace talks in San Vicente del Caguán in 1999, when the FARC’s leadership left their seats at the negotiating table empty. The event embarrassed then-President Andrés Pastrana and bolstered the perception of Caguán as a guerrilla stronghold, often referred to as “Farclandia.”

Following the 2016 peace agreement, the Pato River valley and the broader Caguán region transformed into a markedly different conflict zone. For peace signatories, this new era has been characterized by navigating both treacherous high-speed rapids and the perils of crossfire between dissident FARC factions.

Paddling for Peace

In February 2023, I met political scientist Carlos Ariel García, a noncombatant ally of Miravalle residents and cofounder of Caguán Expeditions. “This place [Caguán] is truly special,” he told me. “There are many historical sites to explore, and it is a well-conserved natural reserve thanks to the guerrilla.” He handed me a business card featuring an image of adventurers in safety gear navigating an awe-inspiring, cavernous gorge and the tagline, “Nature, Adventure, and Historical Memory.”

Run by demobilized combatants, Caguán Expeditions is an example of peace signatories’ entrepreneurial labor, known locally as “emprendimiento,” a crucial step in socioeconomic reintegration.

Among other offerings, whitewater rafting on the Pato River became Caguán Expeditions’ main source of income, garnering international attention as a successful peacebuilding project. The group also trains local campesino youth in rafting and kayaking. On an oral history route, Caguán Expeditions guides tourists through San Vicente del Caguán and across a pedestrian bridge over the Caguán River, into which the Pato River flows. Tourists learn about how, during the armed conflict, the FARC gained overwhelming local support by building and maintaining transportation infrastructure and providing other essential services in regions neglected by the state. As the peace signatory guides would insist, fauna and flora in the region have been preserved thanks to the FARC’s nature conservancy policies.

Peace Deconstructed

Before heading to Caguán from Bogotá in early January, I contacted Caguán Expeditions to inquire about safety. “There are at least three civilian minivans departing daily from San Vicente passing through that road towards Neiva,” assured a staff member. “You should be fine.” Even after laying down their arms, ex-combatants continue to distinguish themselves from ordinary “civilians.”

Conspicuous coca fields notwithstanding, the lush green road leading into the Pato River valley revealed troubling signs that peace—or at least the absence of armed conflict—was waning. About 40 kilometers (25 miles) after leaving the paved road outside of Neiva, I was welcomed to the region by a banner displaying an almost life-sized photograph of the late Manuel Marulanda, the nom de guerre of Pedro Antonio Marín, the FARC’s enigmatic cofounder and long-time leader. The sign declared the presence of the Darío Gutiérrez front of the EMC’s Jorge Suárez Briceño’s bloc.

Considering the EMC’s innovative use of social media to recruit youth, it was intriguing to observe the mix of novel and tried discursive frameworks on this sign. Heralding “60 years of struggle,” the banner declared: “The struggle for land, territory, and food sovereignty will always be founding principles of the revolutionary process. We invite you to join our efforts, so that together we can build a peace with social and environmental justice.”

Originally founded as a Marxist-Leninist movement in 1964, the united or original FARC would have celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2024 had the secretariat not instructed its ranks to lay down their arms in 2016. The banner’s subtext emphasized the EMC’s rationale for persisting with the armed struggle, unlike peace signatories, whom they accuse of betraying the revolutionary cause. Despite this, most peace signatories still identify with the FARC through their political party, led by former top commander Rodrigo Londoño, also known by his nom de guerre Timoleón Jiménez or Timochenko.

As I ventured closer to San Vicente del Caguán, passing through eerily silent residential areas and abandoned Army outposts, the signs of ongoing hostilities became clearer. Spray-painted graffiti on the façade of buildings announced the EMC’s Iván Díaz front. Below, red aerosol paint crossed out a recognizable stencil-made blue emblem, also featuring Marulanda, but with a different name: “Second Marquetalia. Teófilo Forero mobile column.” The dissident FARC of the EMC were no longer facing the Army in this region—or their allied shadow forces, the deadly right-wing paramilitaries—but a rival FARC dissident faction, Second Marquetalia.

Although both the EMC and Second Marquetalia are engaged in peace talks with President Gustavo Petro’s administration and have agreed to ceasefires, internal divisions and a lack of a well-defined and experienced chain of command within the EMC have led to its fronts acting independently. Some units are no longer part of the ceasefire.

The Second Marquetalia, on the other hand, is mostly composed of high-profile peace signatories, many of whom used to belong to the FARC secretariat, the guerrilla’s top central command. Commander Iván Márquez, nom de guerre of Luciano Marín Arango, for example, renounced his seat in Congress in 2019 and resumed armed struggle in protest of the government’s reluctance to implement the peace agreement, especially its provisions regarding integral rural reform. The Second Marquetalia thus preserves its vertical chain of command and operates with a unified strategy.

Historical Memory, Inc.

In Miravalle, although the majority of former combatants opted for demobilization and pursued vocational training to kickstart entrepreneurial ventures, the sustainability and success of these “emprendimientos” were not assured. A planned fish farming project, for example, didn’t pan out. Despite significant investments in constructing fish tanks and Latin America’s first hydroscrew to power them, fluctuations in mountain temperatures made regulation challenging, and the Pato River’s strong currents destroyed the clean energy generator. The fish farming venture failed.

Another project, the woman-led coffee initiative Crafepaz—a brand name that combines the letters of FARC-EP with the word paz or peace—also faced hurdles. Since peace signatories lacked their own fields, they had to procure beans from local campesino growers, diminishing their profits over time. Like other enterprises, the brand symbolizes a fusion of former combatants’ past and their pursuit of peace. In a balancing act between marketing and historical memory, Claudia Beltrán, the peace signatory depicted on Crafepaz’s logo, and other former FARC women recognized the value of subtly encrypting their identities to expand their commercial reach beyond the Caguán region, particularly in areas with less historical support for the guerrilla.

For Caguán Expeditions, cofounder García and peace signatories at Miravalle understood the competitive advantage their tourism offerings held over other emerging initiatives. Their project presented a unique opportunity for Colombian nationals and international tourists to learn firsthand about the storied history of Caguán—a region that long haunted the country’s sociopolitical imagination.

“We want visitors to take in the history of this region, hearing about the unfolding of events leading up to the contemporary moment, from peace signatories themselves,” explains García, who began working with Miravalle’s residents in 2017 as a delegate for the Office for the High Commissioner for Peace. “We see it as a necessary step to dispel long-held stigmas portraying people from Caguán as inherently violent. The FARC built not only a culture of resistance but also skills and knowledge attuned to the territory, which we call historical memory.”

With 3,000 visitors in 2023 alone, the resounding success of Caguán Expeditions was a living testament to how the historical tapestry of this FARC heartland could be harnessed to sustain signatories’ post-accord livelihoods.

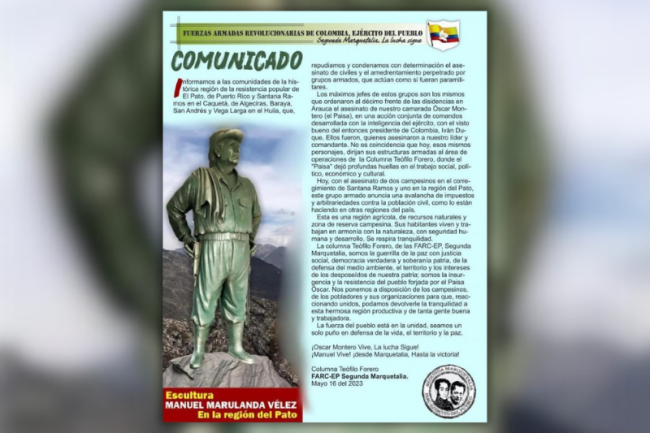

On Caguán Expedition’s oral history tour, the final stop is a unique community-funded museum dedicated to Manuel Marulanda, located in Miravalle. At the entrance, an impressive 8-foot bronze statue of the revered guerrilla leader welcomes visitors. Serving as a guide, peace signatory Adriana Villa passionately recounts a timeline of leftist-inspired events, beginning with the formation of the Colombian Communist Party in 1930.

“This entire campesino natural reserve where we stand today has its origins in communists and radical liberals who fled bipartisan strife during La Violencia,” Villa explains. La Violencia, the violent conflict that gripped Colombia from 1948 to 1958, soon gave way to the formation of leftist guerrillas. “The elderly here vividly recall whole campesino families settling in the valley, only to later depart due to persecution.” The government’s crackdown on campesino rebels culminated in the valley’s bombardment in 1965, referred to as the “March of Death.”

Wrapping up the timeline with the 2016 peace accords, Villa offers a poignant statement that resonates with the EMC’s banner: “As FARC, our struggle has always been aimed at achieving peace, but a peace with social justice.”

Reliquary of the Revolutionary Army

If Marquetalia, a hamlet in Tolima state, was the mythical birthplace of the FARC, the government’s persecution made the Pato River basin its historical refuge. In his self-published 2020 manifesto stating his reasons for retaking arms, Iván Márquez relates how, in life, Marulanda envisioned Caguán as a rebirth of Marquetalia—a second Marquetalia.

The fact that the EMC and Second Marquetalia are warring against each other for control over the Pato River valley and broader Caguán region led me to wonder if the intragroup conflict was driven not only by the valley’s strategic military weight but also by its symbolic heritage.

“El Pato is not only important as a rearguard for the guerrilla, for us to fall back on when the Army pressed elsewhere, but it is also where the tombs of FARC cofounders Jacobo Arenas and Manuel Marulanda are located,” explains Mayerli Pinilla, a peace signatory and geography major at the Universidad del Valle in Cali who, during the conflict, received direct orders from Marulanda in Caguán. While Marulanda was the military strategist, Jacobo Arenas, nom de guerre of Luis Alberto Morantes, is regarded as the FARC’s leading intellectual and ideologue.

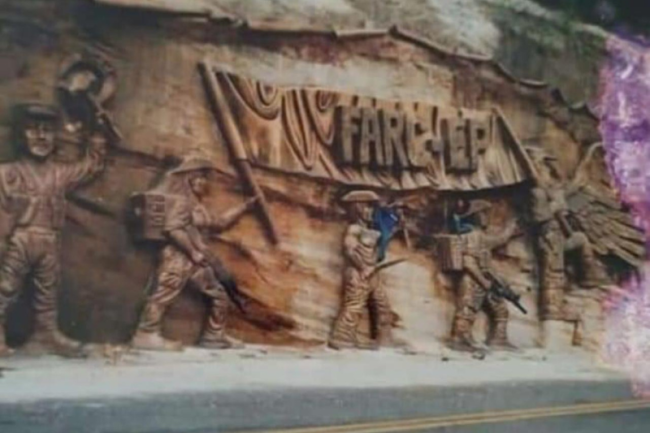

So entrenched was the presence of the guerrilla in Caguán that, in the 1980s, the group created a monumental bas-relief sculpture depicting an idealized revolutionary march, complete with a FARC banner, next to the Pato River on the outskirts of San Vicente del Caguán. According to locals, this testament to the guerrilla’s dominance also served as a transaction point where affluent cattle ranchers would deliver the “revolutionary tax,” known as the vacuna, to FARC soldiers. This sculpture, however, was destroyed by Colombian Army explosives in 2001 following the collapse of President Pastrana’s peace dialogues.

These histories also influenced the choice of location for the Miravalle reintegration camp. According to peace signatories I spoke to, the mountain ridge where Miravalle is situated was personally chosen by FARC commander Hernán Darío Velásquez, also known as “El Paisa,” for both its strategic positioning and proximity to significant historical sites. El Paisa later abandoned the peace process to take up arms with Second Marquetalia and was killed in combat in 2021.

All three splinter groups—EMC, Second Marquetalia, and FARC-identifying peace signatories—acknowledge the Caguán and Pato River’s geopolitical and symbolic hold. This dual significance of the Caguán means territorial control of the region could bolster aims by dissident FARC groups to political recognition in peace dialogues. For all three groups, it could also unravel the crisis in symbolic legitimacy and foster social cohesion amid the ongoing divisions within the guerrilla factions in the post-peace agreement era.

Uncertain Futures

In response to the EMC’s threats, Caguán Expeditions launched a crowdfunding campaign to gather the resources for their relocation. It is unclear if they will be able to continue rafting on the Pato River.

Meanwhile, facing major peacebuilding setbacks, Petro’s administration appears to be contemplating a shift from a dialogue-focused “total peace” policy to a traditional U.S.-led counterinsurgency strategy. In July, the president proposed extending the peace agreement’s 15-year implementation period by another seven years.

Regarding the future of Miravalle’s other peacebuilding projects, Adriana Villa explained: “A priest from San Vicente has kindly allowed us to use one of the seminary rooms to house our coffee-processing machinery. However, relocating the museum is a far greater challenge.” When asked what they were planning to do with Marulanda’s statue at the museum, García refused to talk about it, citing security concerns. Upon further investigation, I obtained a copy of a “comunicado,” dated May 2023, and signed by the Second Marquetalia. The leaflet, which circulated in the area, includes a picture of the Marulanda statue; this surely fueled the EMC’s accusations of collaboration between their rival faction and Miravalle’s residents.

It is no wonder, then, that people in the broader Caguán region are hesitant to support the museum and its efforts to relocate the statue, as the specter of Marulanda and his lingering influence continues to cast a shadow over the region.

Alejandro Jaramillo is a freelance photographer, filmmaker, and PhD candidate in sociocultural anthropology at New York University. Supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and Bogotá's El Rosario University, his multimodal research delves into the intricate world of former FARC combatants as they navigate socioeconomic reintegration.