Ana Margarita Gasteazoro (1950-1993) lived a remarkable life as a clandestine political activist and political prisoner in El Salvador. Deeply self-reflective and powerfully narrated, her memoir Tell Mother I’m in Paradise offers a complex portrait of a woman who transgressed multiple social words. Gasteazoro intimately describes how ordinary Salvadorans survived state terror and organized revolution. The memoir is a gem of a source that will capture the attention and hearts of multiple audiences.

Gasteazoro traces the gradual radicalization of her political consciousness, which unusually began when she was a curious upper-class adolescent who questioned her fascist Catholic upbringing. As a young woman, she traveled to multiple countries in pursuit of love and personal autonomy, and eventually arrived at social democratic politics. But state terror, electoral fraud, and leftist politics further radicalized her. And so, in the late 1970s, she made the life-altering decision to join an armed revolutionary movement, which fought to overthrow a U.S.-backed military dictatorship and build socialism. While Gasteazoro did not fight as a combatant, she nonetheless risked her life as a clandestine political activist. In May 1981, the National Guard disappeared and tortured her for 11 days. She then spent two years organizing within a women’s prison. Upon her release, she lived abroad and coordinated solidarity work. She later opened a café with her partner and critically reflected upon the dogmas that undermined revolutionary theory and practice.

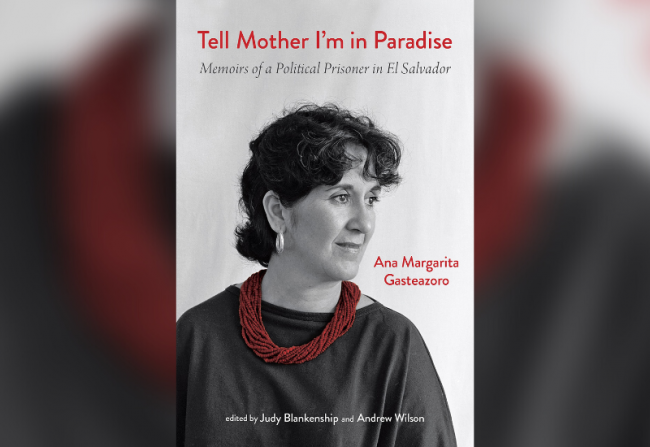

This memoir was a long-time coming. Gasteazoro’s close friends, Judy Blankenship and Andrew Wilson, interviewed her for countless hours and edited the transcripts for her approval. Unlike most Latin American memoirs, this one was first produced in English, due to Gasteazoro’s fluency and the interviewers’ monolingualism. After much internal debate, the family approved the memoir for publication almost three decades after Gasteazoro’s fatal battle with breast cancer. In 2019, the memoir was published in Spanish by the Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen and has now been released in the original English.

The section “A Nice Girl Like Me” portrays the oligarchic society in which Gasteazoro’s family lived. Her four siblings—a priest, lay nun, businessmen, and chemical engineer—fulfilled the expectations of their right-wing family. And it initially seemed that Gasteazoro was on a similar path. Her mother, who remained unnamed throughout the memoir, was a lifelong member of Opus Dei, a fascist Catholic organization that advocated strict gender segregation and patriarchal gender roles. Mother spent her days arranging fresh-cut flowers and attending mass, while seven domestic workers maintained her home. As a child, Gasteazoro attended Opus Dei activities, learning gourmet cooking, etiquette, and other skills that would make her a respectable wife. Upon her liberal father’s insistence, she attended a co-ed, English-language school that educated the children of U.S. embassy officials.

Gasteazoro’s social rebelliousness began to awaken in early adolescence. To keep her from smoking and partying, 15-year-old Gasteazoro was sent to an all-girls school in Guatemala run by Maryknoll nuns, including Sister Marian Peter, who later became a famous anti-war activist in the United States. Gasteazoro’s parents were ignorant of the nun’s political activities, which included providing social services to shantytown residents. Gasteazoro soon developed a close relationship with María Cristina Arathon, a 25-year-old psychologist who took her to the mountains to witness first-hand the miserable conditions under which Indigenous people labored. These experiences made Gasteazoro reflect upon the class divides back home: “Since I had got used to walking in the poor barrios and sitting at the same table with working-class people, I couldn’t understand why we had to have such gulfs between rich and poor in El Salvador.” After high school, Gasteazoro worked to secure her independence and lived in multiple countries abroad. Meanwhile, her parents opposed her various romantic partners—often because of anti-Black racism—and impeded three different engagements.

The section “A Nice Country Like El Salvador” describes how growing state violence targeted reformers and radicals alike. In the late 1970s, Gasteazoro joined the National Revolutionary Movement, a legal political party of intellectuals and social democrats. Her fluent English and strong administrative experience made her a skilled public writer and spokesperson at international conferences. Often the sole woman, Gasteazoro fought to “be taken seriously in the party with half of these men relating” to her as a “sexual object and half as a political colleague.” But she grew increasingly disillusioned with the efficacy of electoral strategies to create structural change, let alone protect political opponents from state violence. She describes a typical week:

I went one under one of the underpasses and there was a body hanging from the bridge. It was a man in his shorts, with a cardboard placard saying, “Death to the traitors of the fatherland.” It was signed by one of the death squads…I saw another body. It was covered by a sheet with a drawing of what was supposed to be the flag of one of the popular organizations on it…there was a third body. The person had been tortured, and the bones were broken. That was our daily routine. Terror followed us.

To build revolution, Gasteazoro joined the Popular Liberation Forces (FPL), the biggest guerrilla organization in the country. The FPL was one of five guerrilla groups that made up the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), an armed insurgency of urban and peasant workers. She wrote propaganda, oversaw the making of a major documentary film, transported weapons and equipment, and ran multiple security houses where groups of comrades lived and worked together. Such work required careful coordination and aliases to circumvent the suspicions of neighbors and authorities. On average, Gasteazoro spent two hours a day on security. And the stakes could not be higher. In one instance of failed security (not under Gasteazoro’s supervision), authorities captured and killed the five-person directorate of the Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition of mass organizations.

The FPL’s strict security culture protected its members from state violence, while inevitably disrupting their personal lives. The organization used the tactic of compartmentalization, which limited “to an absolute minimum” the knowledge members had of each other’s identities and activities. As Gasteazoro describes, “What you don’t know you can’t reveal if you’re arrested.” Clandestine life produced a series of contradictions that she and others struggled to navigate. “The reality is that you’re living together, sleeping in rooms next to each other, and you need love—holding someone and being held,” she says. “But the rules of clandestine struggle say you must control yourself with the same discipline you bring to the rest of your work. They demand that you be an ascetic. And I’m not.” Gasteazoro soon developed a romantic relationship with her committed, yet dogmatic, comrade Sebastián, who often justified sexism in the name of militancy and shut down political debate with accusations of bourgeois deviation. Years later, he would end their long-term relationship to date a more “disciplined” woman.

Sebastián and Gasteazoro were arrested together when the National Guard knocked on their door in 1981. Since the morning of her arrest, Gasteazoro had been told that her family had abandoned her. But a glimmer of hope emerged in between the beatings. Her mother and brother had secured a quick meeting with her due to their close relationship with the National Guard commander, Vides Casanova. Despite the scolding, their “family solidarity, offered unconditionally across a huge chasm of ideology and past argument,” gave Gasteazoro strength. She had survived torture, sexual assault, and a hostile press conference. And unlike other comrades, she was alive to organize with other political prisoners. The prison secretary asked Gasteazoro if she wished to send Mother a message. She reflected:

I was alive, my family still loved me, life was beautiful, even concrete-walled Ilopango [prison] was beautiful.

“Yes,” I said. “Tell Mother I’m in paradise.”

Without charges, Gasteazoro was detained for two years at the Ilopango women’s prison, an experience she describes in the section “A Nice Prison like Ilopango.” At its maximum capacity, her prison unit, which was one of three, housed about 100 women who slept next to each other with only a space of two tiles separating their beds. Aside from the political activists, other inmates included teenage girls, sex workers, and elite women who had committed financial fraud and apolitical kidnappings.

Gasteazoro joined the directorate of the Committee of Political Prisoners of El Salvador (COPPES). The group confronted miserable prison conditions, violence from apolitical inmates and gang leaders, and sectarianism among the political prisoners who represented competing organizations. In response, Gasteazoro and others collectivized food production, organized activities from gardening to beekeeping to sustain morale, and led hunger strikes to win improved conditions and denounce U.S. imperialism. She also led the discipline committee, which kept relative harmony among inmates. Mothers of disappeared children risked their lives to support the hunger strikers, sneaking messages into their bras to facilitate communication between various prisons and organizations. Overall, Gasteazoro powerfully narrates the solidarity, friendships, romances, traumas, and conflicts that shaped the daily lives of inmates.

Gasteazoro survived paradise to tell her story. With vivid detail, this memoir describes the relationships and organizing process that made revolutionary struggle possible. It will surely leave a lasting impression on readers.

Diana Sierra Becerra is a historian and popular educator. Her book manuscript documents the revolutionary praxis of working-class peasant women in El Salvador.