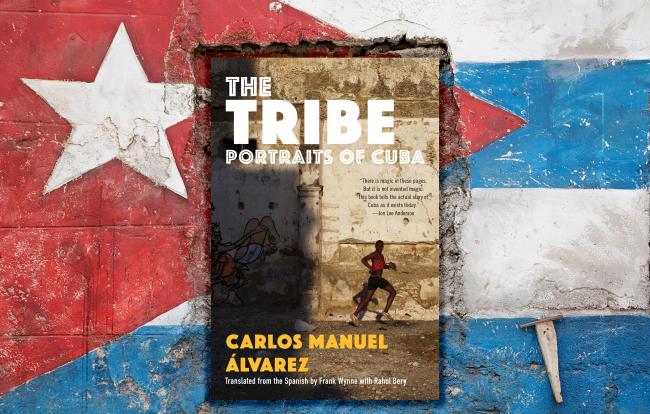

Carlos Manuel Álvarez is one of the preeminent voices of millennial Cuba. In The Tribe: Portraits of Cuba, the internationally acclaimed writer and activist presents aspects of his homeland rarely covered by the international media.

The book is largely based on a 2017 Spanish-language edition of Álvarez’s reportage of Cuba and Cubans and includes more recent material that takes his portrait of island life into the beginning of the San Isidro era (2018–present). Álvarez’s chapters are led by his characters: black marketeers, unhoused people, the urban poor, and many more. Together these individual stories add up to a picture of the nation—a picture that often emphasizes the failures of the state.

Many of the personalities introduced in The Tribe are brilliantly memorable. Chen, 64, and Luz María, 39 going on 60, lead a community of treasure hunters at the Bote de Cien, a landfill site on the outskirts of Havana.

Searching the island’s largest scrapheap for junk to resell can earn the treasure hunters the average monthly wage ($25) in just two days. Some of the treasure hunters are day-trippers, others stay for a few days or a few months. Chen and Luz María, who have made shacks beside the dump, reside there full time.

“The class I really belong to, [is] the honest underclass,” Chen says. “The millionaire belongs to one class, the semi-millionaire to another, and I belong at the bote.”

Chen knows the rhythms of the bote, or landfill: after the army trucks dispense their load, he saves the discarded marmalade and the freshly baked bread. He and Luz María compete to be the best chef at the dump. The ingredients are challenging. Álvarez tells us that “the most protein-rich delicacy to pass through their shack was the dark shapeless mass of meat—chicken, they claimed—simmered in boiling water after four days spent rotting.”

By including many different stories, Álvarez provides a cross section of Cuban life. Chen and Luz Maria’s story of survival is juxtaposed with the workers at all-inclusive tourist hotels who smuggle relative luxuries—cheese, ham, and rum—out of the resort. Álvarez explains how, when an impromptu inspection is called on a day when the workers have already made a deliberately incorrect inventory, they hide the unaccounted food by taping it to their stomachs, backs, legs and even feet.

Some of the produce is consumed by the hotel workers and some is sold on the black market. In one chapter, Álvarez describes how Mauro and Fidel—two students who needed funds for their studies and, in Mauro’s case, to support his whole family—began their unauthorized business distributing items such as cookies and spaghetti.

The pair bought goods in Havana and would sell the products in the town of Colón at a 67 percent markup, taking advantage of the scarcity of most foodstuffs in the interior. In the other direction, cheese bought from farmers in Colón was sold to pizzerias in Havana for a similar profit. To avoid checkpoints, Mauro and Fidel would travel in Cuba’s tourist-serving buses, which are rarely searched by police.

The government’s inability to produce and distribute foodstuffs effectively is clear from another of Álvarez’s vignettes. On one occasion, the state-run Provincial Poultry Company in Matanzas blamed an egg shortage on the weather. Rather than assess its shortcomings, the company excused itself by explaining that the hens were suffering from stress induced by low temperatures, lack of sun, and strong winds.

Similar inertia is prominent in the chapter where Álvarez provides his sharpest criticism of the state. Despite clear signs of decrepitude in several buildings in Jesús María, an impoverished Havana neighborhood, the government took no action until after a balcony collapsed and killed three sixth grade Afro-Cuban girls.

To try to prevent another tragedy, resident Jorge Ortega slept outside every relevant government department. His greatest concern was for what Álvarez calls “the truly terrifying facade of the bodega on the corner of Vives and Florida.” He describes the bodega saying, “A deep crack runs from top to bottom, and panes of glass hang precariously from the two upper windows.”

Again, bureaucracy gets in the way. Ortega explains: “They keep saying that…a form has to be filled in that needs to be authorized by God knows who. The customers who use the bodega and the butchers are going to wind up as corpses under the rubble of this building. Because sooner or later it’s going to collapse, make no mistake.”

Throughout the book, Álvarez highlights the diversity of Cuban people. They may live on the same island and under the same political system, but they retain vast differences based on race, class, and geography. Given that diversity, the title of his collection—which Álvarez does not explain—seems incongruous. His characters resist homogenization, and it is odd that he frames them as something as cohesive as a tribe.

Álvarez is at his best when recounting the lives of marginalized people, telling their stories with enough detail to satisfy even the keenest overseas observers. Taken as a whole, Álvarez’s portraits are a series of rich snapshots of Cuban life.

Daniel Rey is a British-Colombian writer and historian.