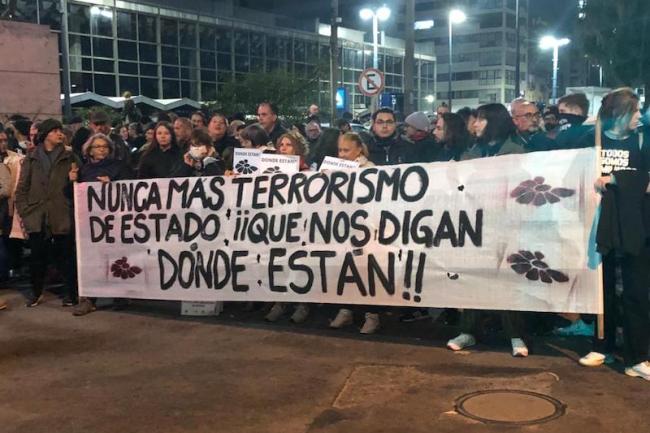

On May 20, 2023, thousands of Uruguayans marched in dozens of places across the country and beyond in one of the largest commemorations of the disappeared since the annual Marcha del Silencio began 28 years ago. The march first took place in 1996 in memory of Uruguayan politicians Zelmar Michelini and Héctor Gutierrez Ruiz, who were assassinated in Buenos Aires in 1976. Over the years, increasingly large crowds have shown up for a massive, silent vigil through downtown Montevideo under the banner “¿Donde están?”—where are the disappeared?

In the years since that first march, memory activities have expanded; there is now not just one day dedicated to the memory of the disappeared but a whole month, the mes de la memoria or month of memory. This year’s Marcha del Silencio came as the country prepared to mark 50 years since the beginning of the Uruguayan dictatorship. On June 27, 1973, President Juan María Bordaberry shut down parliament and turned governing power over to the military. His autogolpe or self-coup officially launched a 12-year reign of state terror characterized by widespread torture, political imprisonment, massive displacement, censorship, and the disappearance of over 200 citizens.

To commemorate the 50th year since the coup, social organizations have staged a series of official and unofficial events. In January, the association of former political prisoners Crysol commemorated the first transfer of prisoners to the most notorious women’s prison, Punta de Rieles. Their homage focused on the children born in captivity and the gendered forms of abuse and discrimination the women experienced there. The following month, further highlighting how repression began well before June 1973, parliament held an event focused on Bordaberry’s February 1973 signing of the Boiso Lanza pact, which allowed the president to remain the official head of state while transferring power to the military. The pact, which The New York Times in March 1973 called a “virtual military coup d’etat,” is often recognized as the beginning of the coup. Meanwhile, Uruguay’s Museo de la Memoria is hosting various installations and exhibits commemorating the anniversary, prominently highlighting 50 years of solidarity and resistance.

These commemorations come at a propitious moment in Uruguay’s struggles over the memory and legacy of state terrorism. Perhaps no example better encapsulates these challenges than recent debates over the implementation of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights decision Maidanik et. al v. Uruguay. For decades, the struggle against impunity for dictatorship-era crimes has been characterized by advances and setbacks. Now, as Uruguay marks the 50th anniversary of the coup, and more survivors pass away, the continuing demand for truth and justice for victims and their families takes on additional urgency.

Struggles Against Impunity

In March 1985, when military rule in Uruguay officially came to an end, victims of the dictatorship filed dozens of court cases seeking to hold the military accountable. The military, however, threatened not to show up in the event of a trial and even hinted at a new coup. In response, in December 1986, parliament hastily passed an amnesty law—the Ley de Caducidad, or expiry law—protecting members of the police and military from prosecution for crimes committed between 1973 and 1985. Despite various legal attempts over two and a half decades to overturn it, the amnesty remained in effect until 2011.

During the years the expiry law was in place, judicial accountability could only be achieved through legal loopholes. In 2010, for instance, former president-turned-dictator Bordaberry was convicted of violating the constitution, forced disappearances, and other crimes, and his foreign minister, Juan Carlos Blanco, was convicted of political killings. These prosecutions were possible because Bordaberry and Blanco were civilian members of the dictatorship and not part of the military.

In 2011, however, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued its first decision regarding Uruguay’s military rule. Gelman v. Uruguay, filed in the inter-American system in 2006, found the state liable for violating several rights and ordered Uruguay to ensure that the expiry law “never again becomes an impediment for the investigation of the facts at hand, and of the identification, and if applicable, punishment of those responsible.” In other words, the Court ordered Uruguay to overturn the expiry law.

Within a year, it did just that. In June 2011, President José Mujica issued Decree 323 to begin the process of removing the law. Then, in October 2011, parliament passed Law 18.831, effectively canceling the amnesty law’s provisions and eliminating the main legal barrier to prosecutions. Other measures of compliance with the Court decision included an official state apology, which was delivered to a full house of parliament in 2012 by, ironically, President Mujica, who was himself a political prisoner of the dictatorship.

The years after the expiry law was overturned did not produce the long-awaited accountability, however. In fact, members of the military did everything they could to avoid trials, for example, by challenging the statute of limitations. Meanwhile, in 2019 a new, far-right political party, Cabildo Abierto, emerged.

Reproducing the dictatorship’s national security discourse and ideology, Cabildo Abierto used its new seats in parliament to advocate for measures such as restoring the amnesty law and granting house arrest to all convicted military officials over the age of 65, which would apply to the limited number of former military convicted of dictatorship-era crimes. Even as a minority party, Cabildo Abierto has enormous power, because President Luis Lacalle Pou is dependent on its members for a governing majority. As of June 2023, Cabildo Abierto refused to vote for a pension reform bill until Lacalle Pou agreed to grant house arrest to all members of the military in the Domingo Arena prison.

Against this backdrop, the Inter-American Court agreed in 2020 to hear a second case regarding violations committed during Uruguay’s dictatorship: Maidanik et al. v Uruguay.

A Second Inter-American Court Case

Filed in the inter-American system in 2007, Maidanik et al. v Uruguay addressed three cases of extrajudicial executions and two cases of forced disappearance, as well as the lack of adequate investigations into the crimes.

The first case dates back to April 21, 1974, when the Armed Forces and police shot several rounds of ammunition into the house where Diana Maidanik (21), Silvia Reyes (21 and 6 months pregnant), and Laura Raggio (19) were sleeping, killing all three. The counterinsurgent military–police Joint Forces said they were looking for Reyes’s husband and falsely claimed that the women had died in a confrontation. The incident is often referred to as the “muchachas de abril.”

The second case in the petition concerns the forced disappearance of Luis Eduardo González (22), detained on December 13, 1974. While the Army initially claimed that González had fled the country, witnesses report that he was subject to severe torture and died in custody on December 26, 1974.

The final case, the latest of the three crimes chronologically, is that of Oscar Tassino Asteazu (40), beaten and detained in his home on July 19, 1977. The Joint Forces took him to La Tablada clandestine detention center where he died after sustaining a heavy blow. The military told his wife that they had no idea where he was.

Both González and Tassino are still disappeared. Uruguay’s official 2003 truth commission claimed that each man had initially been buried in one of the Army battalions, but that toward the end of the dictatorship in 1984, the military allegedly burned and tossed their remains in the Río de la Plata as part of the an alleged coverup, known as Operación Zanahoria. However, Operación Zanahoria is now believed to have been an intelligence foil meant to discourage the search for and exhumation of bodies in military quarters.

These cases were originally filed in Uruguay as early as June 20, 1985, during the initial transition to democracy, but were archived once the amnesty law was passed in 1986. Although the Instituto de Estudios Legales y Sociales de Uruguay (IELSUR), the human rights law group representing the plaintiffs, attempted to reopen inquiries in 2005 during President Tabaré Vázquez’s first term in office, the judiciary refused. As a result, the victims’ families turned to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). Because of the backlog of cases, it took IACHR more than a decade to refer the case to the Court. For victims and families in these and other cases, the struggle to see their day in court has been unduly long.

On November 15, 2021, the Court finally issued its decision. It found the Uruguayan state guilty of various crimes, including forced disappearances and lack of adequate investigations to determine what occurred, and where appropriate, to punish those responsible. Even though Uruguay’s expiry law had been officially overturned 10 years prior, the Court concluded that the Ley de Caducidad had continued to impede investigations. At the time of the ruling in 2021, more than 44 years after the disappearances, there was “no record of effective actions undertaken,” according to the Court. “In this aspect,” the ruling continued, “the State has not shown due diligence” and “did not conduct [actions] diligently to avoid those delays.”

Implementing the Orders

As part of various compliance orders, the Court commanded the state to hold a public ceremony acknowledging responsibility. This is a common measure, and in the 2011 Gelman case, Mujica’s apology was a widely covered event in the country and internationally. In Maidanik, however, even the participation of President Lacalle Pou proved to be a point of high contention amid charged debates over the memory of the dictatorship.

The event was initially slated for May 11, 2023. In the preceding weeks, senator Guillermo Domenech of Cabildo Abierto said that his party refused to pay homage to the “muchachas de abril” because, as he falsely asserted, “these were not girls, they were committed to a guerrilla movement.” In the following days, Lacalle Pou also refused to participate in the public ceremony. In a far cry from President Mujica’s widely publicized 2012 acknowledgment of state responsibility, Lacalle Pou decided to send his vice president, Beatriz Argimón, to the event in his place.

In response, the Association of Madres y Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos del Uruguay, simply known as Familiares, came out strongly against Cabildo Abierto. Familiares is a leading human rights organization in the struggle for truth and justice that first began searching for their loved ones during the dictatorship and has never stopped. They fiercely contested Domench’s categorization of the victims and argued that the president’s failure to attend the public apology violated the Court’s orders. As a result, Familiares refused to participate, and the May 11 ceremony did not occur. The government rescheduled the event for June 15, conveniently when Lacalle Pou would be in New York, with plans for Vice President Argimón to officiate the event.

Amid these debates over the legacy of the dictatorship and the state’s responsibility to the Inter-American Court, the Marcha del Silencio took to the streets in support of truth, memory, and justice. The image of a margarita (daisy) with a missing petal, long a symbol in Uruguay associated with the search for memory and justice for the desaparecidos, appeared in force around the country.

Yet, looming over the impressive march—now multigenerational in its composition—and stunning visual displays of support for the decades-long pursuit of justice were the persistent challenges. In a press conference about the march, Alba González, the mother of a disappeared man, called out Lacalle Pou for his government’s failures to comply with the Maidanik decision. “How many steps back do we have to take in this country?” she implored.

Ending on a resilient note, however, González also highlighted how people have “taken into their own hands the task of sustaining memory.” The struggle for justice “covered the entire town,” she said, referring to the proliferation of daisies symbolizing the demand for the search for the disappeared. Uruguayans, she added, are “a people who do not remain silent…who refuse to forget even if people try to silence them.”

Indeed, a new breakthrough came on June 6, when forensic anthropologists, who have been searching for the disappeared in military barracks since 2017, uncovered more human remains at the 14th Battalion. Less than two weeks later, newly released military secret files, Archivos del Terror–Uruguay, were uploaded to the internet by anonymous sources (possibly intelligence agents). The discovery of bones and the subsequent document leak has renewed calls for accountability around the country amid a moment of heightened awareness of the need for the recognition of these crimes.

It has been 50 years since the coup officially began, but Uruguayans began their fight against the imposition of dictatorship even long before June 27, 1973. Now, in an ongoing struggle since the country’s return to democratic rule, an ever-increasing multigenerational and multi-ethnic coalition of Uruguayans and transnational allies continues fighting for truth, justice, recognition, and accountability. The struggle of memory against oblivion is far from over.

Debbie Sharnak is Assistant Professor of History and International Studies at Rowan University. She is author of Of Light and Struggle: Social Justice, Human Rights, and Accountability in Uruguay and coeditor of the forthcoming volume Uruguay in Transnational Perspective.

Gabriela Fried Amilivia is Professor of Sociology and Latin American Studies at California State University Los Angeles and author of State Terrorism and The Politics of Memory in Latin America: Post-Dictatorship Generations in Uruguay (1984-2004) and editor (with Francesca Lessa) of Luchas Contra la Impunidad: Uruguay 1985-2011.