Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

The victory of opposition candidate Sergio Garrido in the governorship race in the state of Barinas on January 9 changes the symbolic map of Venezuela’s internal diatribe.

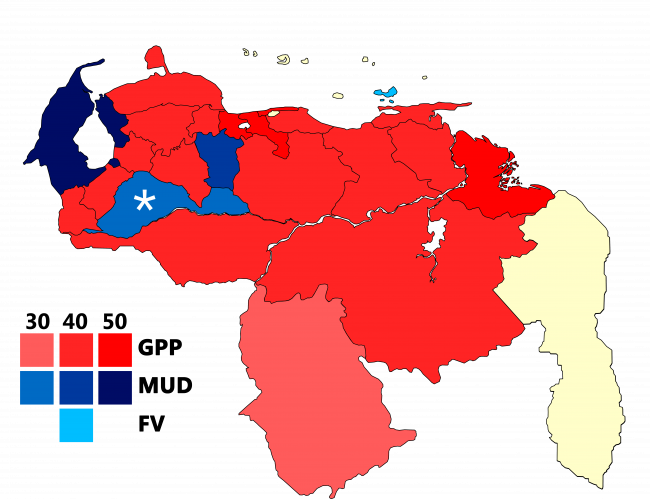

The result barely affects the country’s political-territorial map; the governing party swept the regional elections on November 21 with 19 of 23 governorships and 210 of 335 mayoralties. However, it does mark a tremendous change in the sensibility with which the opposition and the government have participated in a political environment that is, if you will, hospitable—for the first time in many years.

When we talk about Barinas, we’re not just talking about a small southeastern state, home to about one million inhabitants, that has scarcely changed the political cartography. It is also the place that the government has dubbed the “cradle of the revolution.” It is the birthplace of the late leader, President Hugo Chávez, who made the state a family fiefdom. His father and brothers have held the office of governor for the past 22 years, cleaning up in every electoral race.

Chávez rhetorically recreated Barinas, the epicenter of the states making up Venezuela’s llanos or plains, to reclaim historical scenes with mythical significance, like the famous 1859 battle of Santa Inés. In that battle, the popular forces overwhelmingly defeated the conservative military that had governed in the wake of the death of liberator Simón Bolívar. With direct references, Chávez used this symbolism in 2004 as a way to recognize the opposition campaign to collect signatures to launch a recall referendum against him and, later, to consolidate a majority to triumph over that challenge at the ballot box.

Barinas was Chavismo’s comfort zone. That’s why it was so difficult to hand it over in the November elections to the only successful governor candidate from Voluntad Popular, the radical right-wing party of Juan Guaidó, led by Leopoldo López.

Sergio Garrido was a candidate with the Democratic Unity Rountable (MUD), a coalition of traditional opposition parties, though it also managed to gain the support of dissident parties outside this alliance, like Avanzada Progresista. Garrido is a member of Acción Democrática, Venezuela’s historically social democratic party. He ended up being the candidate in Barinas after the Supreme Court disqualified Freddy Superlano, the winner of the November 23 vote, as well as his wife, Aurora Silva, who is also a member of Guaidó’s Voluntad Popular. With incomplete results showing a less than 1 percent margin of victory for Superlano over incumbent Chavista candidate Argenis Chávez, the Supreme Court scrapped the vote and ordered a re-do in January.

It seems clear that the government carefully managed the handing over of the governorship to the opposition in the sense that it decided to cede to a candidate that was less radical than Superlano, who had participated in opposition efforts to overthrow Maduro.

Losing Barinas has been a bitter pill to swallow for Chavismo as a whole. However, after the January 9 vote, President Nicolás Maduro quickly met with the new governor at the Miraflores palace. The losing Chavista candidate, Jorge Arreaza, accepted defeat before the National Electoral Council had even announced the final results, which gave Sergio Garrido a 14-point lead.

Barinas represents not just a question of symbolism, but also of strategy. This defeat has revealed the erosion of the main maneuvers the government relied on both in these most recent regional elections and in the 2020 parliamentary elections: high abstention, a divided opposition, and its own political-electoral machinery. Each of the three has proved powerless to stop an opposition win, laying bare expectations around the next potential major turning point: the 2024 presidential elections. That is, assuming a recall referendum has little change of happening before then.

In the regional elections, the opposition as a whole, added all together, won over 300,000 votes more than the governing party. And in Barinas, real internal opposition division was prevented by the fact that the dissident opposition candidate who ran won just 1 percent of the vote. These facts reveal that, by participating in elections—after having boycotted elections since 2017—the opposition can overcome legal and political obstacles. Such obstacles include the disqualification of candidates by the Supreme Court, as well as the abstentionist line pushed by powerful lobbies in south Florida, which label anyone who bets on the electoral process as “collaborators” of the regime.

These radicalized groups surrounding Guaidó’s interim government have maintained a double discourse around the results: they support the victory but continue to repeat that there are not adequate conditions to participate in elections. However, the parallel government’s political weakness—which now has an international dimension after losing the support of the European Union and many Latin American countries—makes its rhetoric around refusing to recognize institutions a useless strategy for winning power and achieving real objectives. That is, beyond controlling confiscated Venezuelan assets in the United States, England, and Colombia.

So it’s the radical opposition who loses the most in Barinas, because the opposition victory does away with the radical options proposed in recent years, like the coup and foreign interventions that seek to wipe out and criminalize Chavismo. Those strategies have failed over and over again. With a completely powerless parallel government, the radical opposition must change its narrative and retreat to an electoral and democratic plan.

Everyone Recognizes the Results

Only in Barinas did all actors recognize the results, as Washington, like various opposition forces, were reticent to recognize the results of the November regional elections.

But after the January 9 vote, the U.S. government congratulated the new government in Barinas, setting aside its refusal to recognize the National Electoral Council and other Venezuelan institutions. The Venezuelan government, the losing candidate, and the radical opposition also accepted the results. And the discontent with the Supreme Court’s disqualification of Superlano’s candidacy after the November vote seems to have dissipated somewhat.

This situation allows us to ask ourselves if there might be a process of political normalization underway and if we might be witnessing the prologue to the political future of a country so accustomed in recent years to huge confrontations. But above all, we also have to ask ourselves about policies in Washington, the biggest ongoing supporter of the parallel government.

If Washington maintains its antagonistic position, it may inhibit a process of institutional normalization. The government will remain entrenched, and its most radical sectors will prevent any outcome that will back them into a corner. The paralyzed negotiations in Mexico, stalled in the wake of the extradition of Maduro ally Alex Saab, raises the question of whether President Joe Biden will perennially continue Donald Trump’s policies toward Venezuela or whether he is waiting for the mid-term elections in November to finish changing course to a more democratic administration and all that entails.

In the meantime, Venezuelan society awaits a peaceful outcome in accordance with the constitution.

Ociel Alí López is a political analyst, professor at the Universidad Central de Venezuela, and contributor to various Venezuelan, Latin American, and European outlets. His book Dale más Gasolina won the municipal literature award in social research.