Colombia’s largest prison for women, the Reclusión de Mujeres de Bogotá El Buen Pastor (The Good Shepherd), is home to 1,888 people. Squeezed between residential complexes and a military academy, the facility abuts the Río Negro canal, a concrete-lined tributary of the polluted Bogotá River. The water is redolent of manure as it sweeps past the prison perimeter. From the opposite bank you can see people appear and disappear in fractured outline as they move through the dim cells of the upper floors.

On October 13, Carolay Bayona spoke at a community lecture along the path across from Buen Pastor. Bayona is a member of Mujeres Libres (Free Women), an organization of formerly incarcerated women that aims to abolish the imprisonment of women and girls. She spent eight years in Buen Pastor, beginning when she was 15 years old. “Prisons, for me, are indefensible,” she argued. “Never, I mean never, did they offer resocialization.” Bayona detailed the pains of her imprisonment: separation from her infant child, damage to mental and physical health, rotten food, cruel guards. Prison authorities violated her basic rights “every day, at every moment, and systematically.” As an imprisoned woman, she suffered a “double punishment.” She lacked necessary menstrual supplies and reproductive healthcare, lacked viable employment opportunities, lacked visitors. “Jails are made for men,” she said, “there is no equality.”

Her testimony is echoed by academic reports: by other women who have survived incarceration in Colombia; by the Colombian Constitutional Court, which has for 25 years asserted the “unconstitutional” state of the entire national prison system; by the family members of imprisoned people; and by the results of the past fourteen months of my ethnographic study of prison reform efforts in Bogotá.

Yet there is hope this dismal situation might begin to change. On March 8, International Women’s Day, President Gustavo Petro signed into law the “Ley de utilidad pública para mujeres cabezas de familia” (Law for Public Usefulness for Women Heads of Household). The legislation is the result of over four years of organizing by Mujeres Libres and other human rights organizations. At the signing ceremony, Petro claimed the law would release nearly 5,000 women from behind bars, nearly 75 percent of Colombia’s female prison population of 6,697 women. After a six-month implementation, it at last took effect this September, although it took until November 27 for a judge to first apply the law to a concrete case.

Whether or not Petro’s claims about thousands of women leaving prison prove exaggerated, the Ley de Utilidad Pública offers an important step towards reducing the misery of criminalized women and their families. The story of its adoption traces how Colombian criminal justice policy is beginning to respond to scholarship, to feminist movements, and perhaps most crucially, to the long-disregarded voices of women directly impacted by incarceration.

“What’s always happened is that organizations from civil society, for human rights, or from the academy have spoken for us,” Claudia Cardona, the founder of Mujeres Libres, told me. “They say ‘Oh those poor women, this is what happens to them when they’re in jail,’ but many [of those people] have never even been inside a prison. Meanwhile we have our own experiences, and we have so much to say…Who other than us, who have lived this problem directly, constantly, systematically knows what we need to resolve it?”

Failed Resocialization and the “State of Unconstitutional Affairs”

Colombian prisons are not intended to hold people perpetually. From 1910, when Colombia abolished the death penalty, through 2021, when the Constitutional Court overturned an effort by conservative President Iván Duque’s administration to introduce life sentences, Colombian courts have affirmed that “resocialization” and “social reinsertion”—not merely confinement or punishment—are meant to be the “fundamental ends” of imprisonment. Yet the reality of incarceration has always chafed with this nominally rehabilitative aim.

Testimonies from the 20th century in Penas y Cadenas (Pains and Chains) by Alfredo Molano and Isla Prisión Gorgona: Imagen y realidad (Gorgona Prison Island: Image and Reality) by Carlos E. Restrepo describe prisons as rife with corruption, disease, addiction, and hunger. Life behind bars became even more precarious in the mid-1990s, when the armed conflict between paramilitaries, guerrillas, and drug-trafficking organizations filtered into Colombia’s prisons. Facilities collapsed and spasms of violence left scores dead. Prisoners mutinied more than 50 times in 1997 alone. Responding to these tumultuous mobilizations, the Colombian Constitutional Court introduced a legal mechanism that has defined how the state conceptualizes the prison system ever since: the “estado de cosas inconstitucional” (ECI, unconstitutional state of affairs).

With Sentence T-153 of 1998, the Court affirmed “the flagrant violation of a range of prisoners’ fundamental rights” throughout the penal system. The “structural nature” of these failures necessitated profound and coordinated reforms. Nothing short of systematic transformation would remedy the problems the Court had identified.

Prison Imperialism and More Women Behind Bars

In response to the ECI, the Colombian state invested in prison expansion and harsher regimes of discipline and punishment. If prisons were overcrowded, authorities reasoned, the state should construct more. If they were chaotic, they should be more harshly controlled. Backed by the United States Bureau of Prisons, in a relationship critics denounce as “prison imperialism,” Colombia built sixteen new prisons and expanded existing ones. At the same time, stricter sentencing laws and intensified policing produced a three-fold increase in the number of people behind bars.

This prison boom not only failed to resolve the problems identified in 1998—it exacerbated them. Violence, neglect, and overcrowding sharpened, prisons became more inaccessible for visitors and observers, and the impact of what legal scholar Norberto Hernández Jiménez calls the “tendency towards mass incarceration” hit marginalized communities the hardest. Women, LGBTQIA+ people, and racialized communities were locked up in more injurious conditions and at increasingly disproportionate rates. Between 1991 and 2018, the number of incarcerated women in Colombia increased by 429 percent. (In the same period, the incarceration of men increased by 300 percent.) Most of these women are from poor backgrounds, nearly half are victims of abuse, and 75 percent are heads of household. Thirty percent are “sindicadas,” meaning they are awaiting sentencing and are officially innocent.

My conversations with members of Mujeres Libres trace the nexus of coercion and precarity that pushes many women into criminalized behaviors. Women turn to criminalized survival economies because of exploitative relationships, because of poverty, or because they could see no other options. “Nearly every woman I met in prison was there because of a man,” one formerly incarcerated activist who prefers not to be named told me.

In 2013 and 2015, the Colombian Constitutional Court once again declared an “unconstitutional state of affairs” throughout the entire national prison system, extending this analysis in 2023 to include temporary detention centers and police stations. The rulings are comprehensive in detailing the needs of vulnerable prisoners and the obligations of the state to protect them. The challenge, however, lies in the gap between what the Court says should happen and what the Court’s rulings accomplish, what the legal theorist Dean Spade refers to as the distinction between “what the law says about itself” and the law’s “actual impact.”

The ECI’s Persistence

A quarter century after its initial declaration, the ECI persists. As Daniel Echeverry, coordinator of the area of prisons for the Comité de Solidaridad con Presos Políticos (Committee in Solidarity with Political Prisoners), explains, a key issue is that the problem overwhelms the capacity of any single body to resolve it. “Many state entities and institutions bear a special responsibility for the ECI,” he told me. Congress, the police, mayors’ offices, the Ministries of Justice, Health, Education, and Labor, the prosecutor’s office, judges, INPEC (Instituto Nacional Penal y Carcelario, National Bureau of Prisons), and more are complicit in the perpetuation of the crisis. Further, “civil society is exhausted by the prison issue.” In some cases, Echeverry said, the existence of the ECI can even impede actions to improve the situation behind bars. Individual judges have refused to take incremental steps to remedy illegal conditions because, they claim, they are unable to do anything until the overarching problem has been resolved.

The result is an exasperating stasis, a crisis held in place and measured by “indicators” that tell us little about what happens to prisoners or how to make their lives more livable. “Everything becomes a problem of gestión (paperwork), and not the guarantee of rights,” Echeverry says. “So when we tell the ministry, ‘look, we have this problem with access to food, they say, ‘no, the thing is, we had this many meetings, or we sent this number of documents, or spent this much money,’ all of which is just paperwork…they want us to get tied up in a world of documents that reflect these indicators, but none of it changes what’s really important, that they’re giving spoiled food to people, or that people lack access to potable water.”

Even when NGOs and government agencies pay attention to these issues, the result is often vague and out of touch with what imprisoned people need. “They only talk about ‘nutrition,’ or ‘health,’ but they don’t talk about the infringements of rights that, within prison, are treated as normal, even though they’re not,” said Cardona.

The Ley de Utilidad Pública: A Step in the Right Direction

The only way to make a serious impact on the ECI is through mass excarceration. The Ley de Utilidad Pública is a step in that direction, if a limited one. For the first time—at least outside of a transitional justice context—Colombian law provides for criminal punishments other than the deprivation of liberty. “Imprisonment is not the only way to repair the ties that have been hurt by the commission of a crime,” Echeverry says. The Ley de Utilidad Pública is a chance to put alternative, restorative tools into practice.

Social science played a key role in the law’s design. As Kelly Giraldo, a criminal attorney and researcher, explained to me, “This law recognizes a slew of investigative efforts and findings related to feminine criminal behavior.” It draws from empirical studies instead of the reactionary “punitive populism” that has marked previous decades of Colombian penal reform.

The Ley de Utilidad Pública allows women who fulfill certain criteria to replace prison time with work that “benefits society.” This labor can be performed for the state or non-profit organizations, for between five and 20 hours a week. For every five hours of work, a week of the original sentence is paid off. Only women charged with specific crimes—including robbery and the manufacture, storage, or trafficking of drugs—that can be shown to have been committed out of “socioeconomic vulnerability” or in “conditions of marginality” are eligible for this benefit. Women sentenced to more than eight years or charged with crimes related to minors or intrafamily violence are ineligible.

Further, women need to be “cabeza de familia" (heads of households). The Ministry of Justice defines the head of household as “a person who is responsible for another, economically, socially, or affectively.” This encompasses women who have children below the age of 18 when they receive their sentence, as well as those responsible for adults incapable of caring for themselves. This broader definition of caregiving owes its presence in the law to the work of Mujeres Libres and allied organizations. “In its early drafts, the law was only for single mothers,” Cardona says. “And we proposed that it be for women heads of household, given that women in prison are not only mothers, but also fulfill other care work, for their parents and for other people.” The law is thus doubly focused on restorative justice: it both provides opportunities for women charged with crimes to do reparative work, and it enables them to continue to care for loved ones who would otherwise be abandoned.

“A warm washcloth”

The law is imperfect. Women need to perform qualifying labor in the same municipality where they reside, yet there are limited spots available, especially in rural areas. The logistical burdens of proving each requirement are onerous, acutely so for people currently in prison. Advocates fear that judges will deny the benefit without reason.

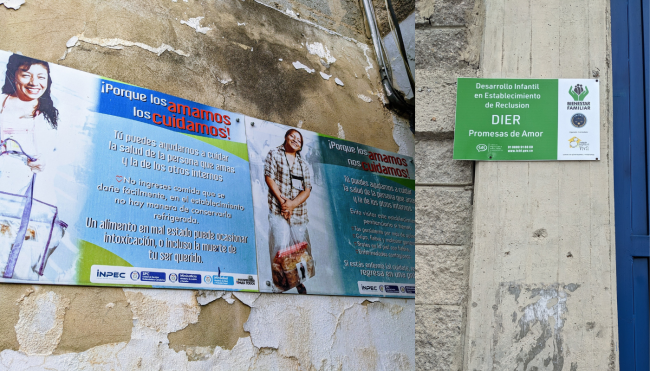

Mujeres Libres knows that legal implementation is never a given. The group was heavily involved in a 2022 law that requires the government to supply adequate menstrual supplies to incarcerated people. However, as Cardona has visited prisons around the country, she has seen that authorities are not abiding by these commitments. The same violations of menstrual health continue. That is why Cardona and other members of Mujeres Libres conduct workshops with imprisoned women, to try to empower those behind bars to claim what the law promises them. In October, they began to teach about the Ley de Utilidad Pública too.

Despite the law’s advances, populations ignored by its terms have little to celebrate. Ana María Medina, one of the directors of the Imprisoned Bodies, Active Minds collective, a project of the Red Comunitaria Trans (Community Trans Network), calls the law “a warm washcloth,” an insufficient bandage for a profoundly damaged system. Trans people face “discrimination, stigmatization, and criminalization at every stage of interaction with the criminal justice system,” but the Ley de Utilidad Pública is not equipped to consider their needs. In Buen Pastor alone, Medina estimates that there are 60 people who identify as trans, including four trans women, and others who “have trans life experiences, but may not identify as trans.” The fact that many trans people have been rejected by their birth families means that much of the care work they perform is illegible to the protections of the new legislation. Trans women stuck in men’s prisons likewise feel excluded. Where does the Ley de Utilidad Pública leave them?

The Ley de Utilidad Pública is not enough to fix the ECI. Nonetheless, it offers a moment of hope to thousands of women facing the maw of Colombia’s wounding prison system. It perceives and seeks to correct injustice. The law, Giraldo insists, “is not a gift. It’s not charity. It’s not, ‘Here you go women, we’re giving you this,’ no…It is the recognition of equality.”

Joe Hiller is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University, with a concentration in Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies. He is a research intern with the Grupo de Prisiones a legal clinic at the Universidad de los Andes. This research was supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award.