August 25, 2010, the corpses of 72 Central and South American migrants were discovered in the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas. The news reverberated across the Northern Triangle of Central America (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala) with an impact similar to 9/11’s in the United States.1 The massacre of the 72, as they came to be known, was a political and social milestone for the region, setting in bold relief the risk of violence that migrants face. Detailed reports of violence saturated Central American media, and Los Zetas, a notorious Mexican drug gang implicated in the Tamaulipas massacre and kidnappings, became a household word synonymous with the class of cruel, professionalized criminal that awaits migrants during their journeys.

Since Central American refugees began moving to the United States during the civil war period of the 1980s, the migratory route through Mexico has been dangerous. In those early days, opportunist criminals, immigration officials, and corrupt Mexican police stalked Central Americans, committing a variety of human rights abuses against them.2 In the 1990s and early 2000s, Central American street gangs controlled the southern train routes through Chiapas, frequently assaulting and terrorizing migrants with machetes and small arms.3 The Sonora desert and the northern border towns have long been infamous for their lawlessness.

Now, however, the violence threatening migrants extends throughout Mexico, not just at the borders.4 Criminal gangs have made a business of targeting migrants, kidnapping them, and demanding that they and their smugglers pay tribute for crossing their territory. In a six-month period from April to September 2010, over 11,000 migrants were kidnapped in Mexico, according to the National Human Rights Commission of Mexico (CNDH).5 During these kidnappings, criminals extort anywhere from hundreds to thousands of dollars from the migrants’ U.S.-based relatives, threatening torture, forced labor, and murder. Women risk rape and being sold into sexual slavery. Children captured in transit suffer alongside adults. Families often pay ransoms by accumulating debt, but migrants sometimes disappear without a trace.

As a migrant Guatemalan youth living along the train tracks in Ciudad Ixtepec put it: “The route is like a war.”6

The safest way to navigate the journey is to pay a reputable guide who knows the appropriate gangs and corrupt authorities to bribe for passage rights through Mexican territory. For upwards of $6,000, migrants can pay for door-to-door smuggling service from Central America to destinations within the United States. Family members in the United States generally sponsor migrants with a combination of hard-earned savings and high-interest loans, paying half the smuggling fee at the outset of the journey and the other half upon arrival. Despite their great expense, even these travel arrangements can end in tragedy: No migrants are immune from kidnappings, rapes, suffocation in hidden compartments, and other calamities during clandestine travel. In fact, migrants with “payment on delivery” agreements have become valuable merchandise, subject to theft by competing smugglers and other criminal groups, because of their potential to pay a large ransom. Some unscrupulous smugglers sell their human cargo to their competitors or kidnappers, cutting their losses and minimizing their own risks of criminal victimization or legal prosecution when trouble arises along the route.

Those who cannot afford an expensive smuggler, despite the precarious conditions, nonetheless press on—clinging to boxcars on cargo trains, begging and borrowing to stay alive, and exposing themselves to predation. Every northbound train from the southern Mexican town of Arriaga, Chiapas, carries hundreds of these people. Their journeys often become an endless odyssey of victimization and repeat deportation. After each calamity, many migrants attempt another journey and another, starting again and again. If you spend a few months on the route, their faces become recognizable, because some migrants pass each place so many times. The accumulated suffering of each attempt adds to their determination, as migrants seek to transform the sacrifices already endured into something worthwhile. Desperate to pay back debt already incurred to pay a ransom, some migrants risk additional kidnappings that might result in their death. Some people make so many attempts to arrive in the United States that the route becomes a last refuge. Like the Guatemalan youth living along the tracks, they wander Mexico without a clear destination, able neither to cross the northern border nor to return south to the violence and poverty that initially motivated their departure. Indeed, their having attempted the trip may mark them as targets for criminal gangs, suspicious of their allegiances, upon their return to Central America. When there is neither hope of arrival nor return, transit becomes a lifestyle. In this way, we are witnessing the birth of an internationally homeless class, enduring vagabond lives along the train routes through Mexico. They are unrecognized refugees without respite from violence.

In El Salvador and Guatemala, governments and rebel groups signed peace accords in 1992 and 1996, respectively. But in the absence of organized political violence, Central America experienced a descent into criminal and police violence, a cannibalism of the poor that reflects the disillusionment of failed revolutions and unmet promises for economic justice.7 That the risks have not deterred hundreds of thousands of Central Americans from migrating demonstrates that, for many of them, conditions at home are so bad that an uncertain path through Mexico still offers hope. An increasing number of them dare the journey to escape the violence of their home communities and reunite with their families already in the United States.8

While the route to the United States is like a war, many Central Americans describe contemporary criminal violence in their homelands as “worse than war.”9 In a comparison of the past and present predicament of his homeland, a Salvadoran man echoed the sentiments of many migrants:

“It was prettier in the past. There had been a war, but there weren’t vagos [gang members]. A soldier, often an uncle or relative, would warn you when they would come looking for you [to draft you]. They would come about every three months, you would be warned and you would hide. But the war wasn’t in the towns. It was in the mountains. Now, for this reason, many people leave.”

Now fear of persecution by criminal gangs haunts residents of urban areas and countryside alike. Central America is the most murderous region in the world.10 In 2004–09, the rate of violent deaths per capita was highest for El Salvador than any other country in the world, exceeding that of wartime Iraq.11 The UNDP Human Development Report for Central America 2009–10 estimates El Salvador’s homicide rate for 2008 at 52 per 100,000, recently exceeded by the Honduran rate of 58 homicides per 100,000 people.12 Homicide rates have risen dramatically across Central America since 1995, but particularly in Honduras, where migration has been accelerating rapidly since Hurricane Mitch in 1998. According to the 2010 Americas Barometer survey of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), 24.2% of Salvadorans, 23.3% of Guatemalans, and 14% of Hondurans report being victims of crime in the last year (including robbery, burglary, assault, fraud, blackmail, extortion or violent threats). 13 Forty-four percent of Salvadorans report feeling either somewhat or very unsafe in their own neighborhood.14 According to the 2010 Latinbarómetro survey, only 3% of Salvadorans never fear becoming a crime victim, making El Salvador the most fearful of all Latin American countries.15 Over half of all Salvadorans and Hondurans report seeing a deterioration of security in their countries, and over two–thirds of all Guatemalans claim their country is becoming “less safe” due to criminal violence.16

Transnational extortion rackets now span Central America with phone calls to victims originating in different countries and payments made through international bank transfers or by money wire. These schemes target the main sources of revenue for the poor and middle class of Central America: the slim profits of street vendors and the remittances received by people with relatives in the United States. Poor women preparing food at the roadside or selling vegetables at market receive demands for exorbitant sums of money, sometimes thousands of dollars. Street toughs insist that shop owners give them “gifts”: prepaid phone cards, food, and other items. Faced with this dilemma, many people simply close shop and leave town. In urban areas, killers, extortionists, and thieves regularly board public transit, discouraging movement within cities.17 Some people fear crossing into neighborhoods controlled by competing gangs in search of work. Whole villages in Guatemala have fled north across the border, fearing violent confrontation between drug gangs and the government.18 As a result, criminal violence and poverty have become intricately intertwined across Central America. In interviews of migrants conducted at shelters and train yards along the route from September 2010 to August 2011, many people at first said they left for economic reasons, but the longer narrative about their lives revealed that violence frequently underpins their difficult economic situations. For example, a Salvadoran man moving north by train described how he was caught between the competing gangs that control Salvadoran neighborhoods, Barrio 18 and MS 13:

“I lived in the territory of the 18. My children lived in the MS community. So, I could not visit my children and they could not visit me. If I had gone into their neighborhood, they would have killed me. I worked where there was 18, and when I was fired, I could not work outside my neighborhood. I would be killed. They cannot leave either. This was my only exit to look for work.”

These two gangs control a patchwork of territory in San Salvador and other major metropolitan areas in Central America. Moving between the neighborhoods raises suspicions about gang involvement and loyalty. Losing his job might not have motivated this man to migrate to the United States if not for the persecution he would have faced if he had sought work in another neighborhood. Others face persecution after rejecting gang recruitment, reporting crime to police, returning from the United States, resisting extortion or spurning the sexual advances of a gang member. For this man and many like him, the danger of the journey through Mexico is an extension of the danger of everyday life in Central America. In what is a sad truism about the everyday violence of Central America, crime reinforces poverty, while poverty reproduces vulnerability to crime. Now, decades after political violence pushed people north en masse, this social disorder drives Central Americans to risk the journey to the United States. Indeed, a 2010 study using Latinobarómetro surveys from 2002 to 2004 concluded that people from a household with a crime victim in the last year are significantly more likely to seriously consider emigration to the United States.19

The governments of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala have taken few effective measures to address the spiral of poverty and violence. Instead, these governments turned to mano dura (iron fist) policies that implement a punitive, militarized law enforcement strategy. But this approach has been counterproductive, spurring the professionalization of street gangs and leading to human rights violations committed by law enforcement.20 Indeed, some people leave Central America not only because they fear criminals, but also because they fear legal persecution by broadly empowered police or extralegal actions by vigilantes.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the plight of Central American refugees captured the imagination of the American left and generated outrage at U.S. policies that simultaneously fueled political repression and closed the door to people attempting to escape this violence. This outrage led to transnational organizing around a sanctuary movement that attempted to provide humane conditions for unauthorized migrants in transit across borders.21 Academics, journalists, and activists challenged the state narrative that Central Americans entering the United States were labor migrants and forcefully argued that they deserved asylum.22

Contemporary Central American immigrants to the United States need broader legal and social recognition as refugees and asylum seekers, as opposed to purely labor migrants. Unfortunately, asylum cases based on persecution by criminal actors are notoriously difficult to win in the United States.23 After having survived torture during kidnappings, rapes, threats, and assaults, many Central American migrants now arrive in the United States without access to appropriate social and psychological support for refugees and survivors of violence.

Although the U.S. asylum system and international refugee regime is not designed to meet their needs, contemporary Central American migrants are refugees. The willingness of so many Central Americans to brave the violence of Mexico exposes the extent and severity of contemporary violence in their homelands. In light of the recent mass kidnappings and killings of migrants, it is again time to challenge the narrative of Central American labor migration. According to the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, a refugee is any person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.” Central Americans fit this definition; in Central America, the “new” refugees flee an escalating cycle of police and criminal persecution based on their social class and refusal to cooperate with criminals, just as their grandparents and parents fled political persecution.

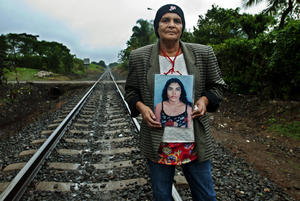

Along the route through Mexico, the kidnappings and killings of migrants fleeing Central American violence have become so common that their mothers and other family members have begun to organize.24 For example, COFAMIPRO formed in 1999 in Honduras and COFAMIDE followed in 2006 in El Salvador. These advocacy efforts recall painful memories from the 1980s, when Latin American mothers leveraged their moral authority against the disappearances of their children by politically motivated death squads. Central American activists, together with Catholic migrant shelters and other human rights groups, have brought the new escalation of disappearances to international attention.

Meanwhile, there are some hopeful signs of solidarity against the violence on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. Over 50 Catholic shelters in Mexico serve migrants during their journey, forming a front line against the abuse of migrants. While the gap between law and practice continues to undermine human rights protection, Mexican activists have won several important legislative victories. In 2008, Mexico legalized humanitarian aid to undocumented migrants. In 2011, immigrants and their advocates won a symbolic victory when Mexico passed, but failed to implement, a sweeping reform aimed at decriminalizing transit migration. On the U.S. side of the border, several U.S. activist groups continue their humanitarian work in the Arizona desert, providing water and lifesaving medical attention to border crossers. Thus, some signs of the resurrection of the social movement for Central American refugee rights have already emerged. This advocacy cannot come too soon for a growing number of people who are refugees twice over: pushed from a place that is worse than a war through a gauntlet that is like a war.

Noelle Brigden is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Government at Cornell University.

1. See José Luis Sanz, Louisa Reinolds, and Juan Jose Dalton, “Masacre en Tamaulipas: Tres viajes, un destino . . . ,” Proceso (Mexico City), 19 (September 2010): 40–43.

2. See Bill Frelick, “Running the Gauntlet: The Central American Journey in Mexico,” International Journal of Refugee Law 3, no. 7 (April 1991): 208–42.

3. See Sonia Nazario, Enrique’s Journey: The Story of a Boy’s Dangerous Odyssey to Reunite With His Mother (Random House, 2006).

4. See Óscar Martínez, Los migrantes que no les importan: en el camino con los centroamericanos indocumentados en Mexico (San Salvador: Icaria Editorial, 2010).

5. CNDH, Informe Especial Sobre Secuestro de Migrantes en Mexico, February 22, 2011.

6. In addition to secondary materials cited here, this article draws on hundreds of interviews of migrants, family members of migrants, migrant shelter volunteers, human rights activists, police, community members and others along the routes from El Salvador through Mexico (2009–11).

7. See Dennis Rodgers, “Slum Wars of the 21st Century: Gangs, Mano Dura and the New Urban Geography of Conflict in Central America,” Development and Change 40, no. 5 (September 2009): 949–76.

8. See Damien Cave, “Crossing Over, and Over,” The New York Times, October 2, 2011.

9. See Ellen Moodie, El Salvador in the Aftermath of Peace: Crime, Uncertainty and the Transition to Democracy (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010).

10. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Study on Homicide: Trends, Contexts, Data (October 2011), available at unodc.org.

11. Geneva Convention, “Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011,” available at genevadeclaration.org.

12. United Nations Development Program, “Opening Spaces to Citizen Security and Human Development: Human Development Report for Central America, 2009–2010,” available at hdr.undp.org.

13. Ricardo Cordova Macias et al., Political Culture of Democracy in El Salvador, 2010: Democratic Consolidation in the Americas in Hard Times (Americasbarometer Report, Latin American Public Opinion Project, Vanderbilt University, November 2010), 85; available at vanderbilt.edu.

14. Ibid.

15. Latinobarómetro, 2010 Annual Report (Santiago, Chile: Corporación Latinobarómeter, December 2010), available at latinbarometro.org.

16. Ibid.

17. See Steven Dudley, “Inside: The Most Dangerous Job in the World,” InsightCrime, March 15, 2011, available at insightcrime.org.

18. Mica Rosenberg, “Guatemalans Live in Fear Again as Drug Gangs Move In,” Reuters, October 2, 2011. 19. Charles H. Wood et al., “Crime Victimization in Latin America and Intentions to Migrate to the United States,” International Migration Review 44, no. 1 (spring 2010): 3–24.

20. José Miguel Cruz, “Central American Maras: From Youth Street Gangs to Transnational Protection Rackets,” Global Crime 1, no. 4 (November 2010): 379–98; Oliver Jutersonke et al., “Gangs, Urban Violence and Security Interventions in Central America,” Security Dialogue 40, no. 4–5 (August/October 2009): 373–397; Sonja Wolf, “Policing Crime in El Salvador,” NACLA Report on the Americas 45, no. 1 (spring 2012): 37–42.

21. Maria Cristina Garcia, Seeking Refuge: Central American Migration to Mexico, the United States and Canada (University of California Press, 2006).

22. Nora Hamilton and Norma Stoltz Chinchilla, “Central American Migration: A Framework for Analysis,” Latin American Research Review 26, no. 1 (1991): 75–110. Andrew R. Morrison and Rachel A. May, “Escape From Terror: Violence and Migration in Post-Revolutionary Guatemala,” Latin American Research Review 29, no. 2 (1994): 111–32; William Deane Stanley, “Economic Migrants or Refugees from Violence? A Time-Series Analysis of Salvadoran Migration to the United States,” Latin American Research Review 22, no. 1 (1987): 132–54.

23. Sebastian Amar et al., Seeking Asylum From Gang-Based Violence in Central America: A Resource Manual (Washington, D.C.: Capital Area Immigrants’ Rights Coalition, 2007).

24. Elisabeth Kirchbichler, “Those Who Never Make It and the Suffering of Those Left Behind: The Fate of Honduran Missing Migrants and their Families,” Encuentro, no. 87 (2010): 71–74.

Read the rest of NACLA's Winter 2012 issue: "Elections 2012: What Now?"