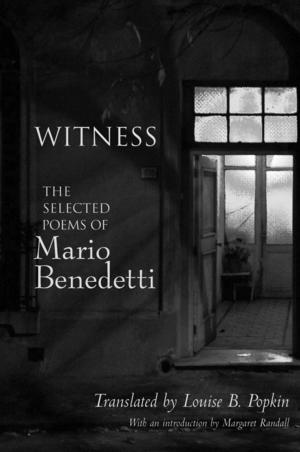

This book brings together selections from a lifetime of work by the prolific and celebrated Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti, and it’s a volume well worth the effort that went into it. Feminist poet, author, and activist Margaret Randall wrote the introduction, which offers an excellent biography and personal reminiscences of Benedetti. The translations were done by Louise B. Popkin, who as Randall points out in her introduction, “spends long periods in Uruguay, knew the poet, heard him read, consulted with him, and has studied his work and entorno (ambience).” In Witness, Popkin “gives us the first really satisfying, accurate, and deeply felt English translations that capture Benedetti’s poetic voice throughout all its periods and range,” writes Randall. The book is published by White Pine Press, one of the last independent presses left in the United States dedicated to producing quality Latin American literature in translation.

Until now, Benedetti has received scant attention in the United States, but he continues to be one of the most widely read and accessible poets in Latin America. Shying away from the surrealism that fascinated Pablo Neruda and the magical realism of the so-called Latin American Boom writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Benedetti gave us simple work that eschews all labels. It is deeply sorrowful and joyous at the same time, a poetry with the heart of flamenco and the elegance of tango, but transcending both in its concern with the universal plight of humanity, even as it is proudly rooted in the Latin American continent. With the publication of Witness, one can only hope that another great Uruguayan writer will now gain a larger audience in North America.

Until now, Benedetti has received scant attention in the United States, but he continues to be one of the most widely read and accessible poets in Latin America. Shying away from the surrealism that fascinated Pablo Neruda and the magical realism of the so-called Latin American Boom writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Benedetti gave us simple work that eschews all labels. It is deeply sorrowful and joyous at the same time, a poetry with the heart of flamenco and the elegance of tango, but transcending both in its concern with the universal plight of humanity, even as it is proudly rooted in the Latin American continent. With the publication of Witness, one can only hope that another great Uruguayan writer will now gain a larger audience in North America.

Benedetti was born in 1920 in rural Paso de los Toros, Uruguay, to a well-to-do family of Italian immigrants. The family fortunes changed, but they still had the means to send young Mario to a private German school where he attended until the Nazi salute was instituted in 1933 and his father withdrew him. After finishing his studies, Benedetti endured the boredom of employment in an auto parts store where he worked as the accountant, cashier, and sales representative, then later as a public servant—unpleasant experiences often mentioned in some of the early poems contained in Witness. Soon, however, he gained entry to the world of editing and writing, and by the age of 25 he published his first book of poems and gained recognition as one of the outstanding members of the Generation of ’45, a literary group organized around the older and already well-established Uruguayan novelist, Juan Carlos Onetti.

Benedetti became politically active in 1949, organizing against Uruguayan military cooperation with the United States. Political themes began to emerge in his poetry in the years leading up to the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and became a central concern thereafter. Already a recognized literary giant, Benedetti became a model for poesía urgente (“urgent poetry”), or “committed” literary work that used a popular idiom to take up political themes and causes. A 1959 trip to New York, the city of “millions of jaws / all chewing their gum,” left Benedetti disillusioned with Western capitalism and hungry for the alternative that the Cuban Revolution offered.

In 1971, Benedetti cofounded the Frente Amplio (Broad Front), a political coalition of left groups that included the Tupamaros, a Uruguayan urban guerrilla group, and two years later he was driven into exile for over a decade by the military dictatorship that took power in 1973. He was in the vanguard of a whole generation of poets, most of them younger than he, who used their voices to denounce the wave of fascism the United States unleashed on the countries of Latin America. Benedetti was privileged to see the Frente Amplio come to power in 2004, five years before his death in 2009.

Witness is a poetic chronicle of passage through the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st, in which the poet’s personal life reflects the larger social, political, and historical changes of the world. Indeed, his work is so integrally connected to the time and locale that it almost seems to be drawn and boiled down from the editorial pages of the newspapers.

As Randall points out in her introduction, “His early poems reveal a characteristically Uruguayan or, more accurately, rioplatense pessimism,” and this is particularly true in the often frustrating post–WWII years in Latin America leading up to the Cuban Revolution. In this period the poet describes having lost his “core like a slow-running clock,” doubtlessly resulting from life in the working-class world where—he writes in the poem “Payday”—“they pay me, of course, at the end of each month / for keeping their books up to date / and letting life go by, / one drop at a time / like rancid oil.” In these poems, Benedetti confronts the problem of the man-made inhumane world, which he would later dedicate his life to fighting, yet here only expressed in the ennui, the desperate sense of helplessness before a system designed to extinguish every “drop” of humanity in favor of numbers in a ledger (or now, a computer).

The Cuban Revolution opened up the question of armed struggle as a path to liberation in Latin America and the world, and Benedetti didn’t shy away from the discussion. In “Angel” he writes of the oppressed who talk of peace: “the horrid savvy shoeshine boy,” the “fourth-level clerk,” the “fool who believes in a flag,” and others who are “too innocent / too carefree / to realize peace depended on an angel / and now that angel has / a finger on the trigger.” The ambiguity here is powerful, forcing readers to make their own conclusions, since they aren’t told for whom the angel is fighting or at whom the angel aims.

Most of these poems are powerful, complex, yet subtle in their simplicity, although some are merely simplistic, working more like jokes with punch lines and lacking the usual elements of music, symbol, metaphor, and image. “Heaven” is an example of such work, in which Benedetti plays again with the celestial dogmas to make a political point and portray the Manichean world of Cold War Latin America. “Our torturers are generally catholic,” Benedetti tells us in the first stanza, but despite their belief in the Trinity and their cause, “when they die they don’t go to heaven / because murderers aren’t allowed there.” In the second stanza he describes the victims as “martyrs” and as possibly even “angels or saints,” “but they don’t go to heaven either / because to them there’s no such thing.” The poem delivers a sharp, poignant message about the ironic realities of the time, but it is relatively flat, with few poetic elements and little that would invite the reader to return to it.

Side by side with such simply agitational verse are beautiful, sensitive poems written about, and to, Uruguay’s political prisoners. In pieces like the one immediately preceding “Heaven,” “I’m Off With the Lizard,” the translator shows her great skill as a poet (the key to translating a poem, after all, is to make a new poem in the target language). She translates “Me voy con la lagarjita / vertiginosa / a recorrer las celdas” as “I’m off with the slithery / lizard / to dart through the dungeons.” Such turns in the target language, where music can be made from a somewhat flatter original, are rare gifts bestowed on translators who listen to their own muse. In this poem, Benedetti calls out the names of those imprisoned by the Uruguayan dictatorship and imagines himself slip “through the iron bars / and leave here and there / right by their bruises / or on their spoons / a few crumbs of respect / a shared silence / and grateful thanks for their existence.”

Benedetti shared the anguish of exile for 12 years (1973–85), along with thousands of other Latin American revolutionaries, poets, artists, and intellectuals, and some of his most beautiful poetry comes out of the pain of one torn from home and left to wander the world. One narrative piece, written evidently toward the end of his exile, is “The Acoustics at Epidaurus.”

In the epigram that begins the poem, Cuban poet Roberto Fernández Retamar tells us, “When you make a sound at Epidaurus / You can hear it higher up, among the trees / In the air.” In the poem, Benedetti wanders with a group of tourists around ancient Greek ruins. He poses so his wife can snap a photo, then he imagines he is testing the acoustics and sends a message to his imprisoned comrades in Uruguay: “and that’s how I confirmed the acoustics were truly perfect / for my secret greetings were heard not just on the steps / but higher up in the air” as they crossed “the atlantic and my nostalgia / and slipped through the prison bars / like a clear dry breeze.”

The poet ironically experienced exile in a new and deeper way on returning to his native Uruguay in 1985. “Home” was no longer “home,” since, as he puts it in “Mulatto,” the exiles had been transformed into “mulattos / crosses between stockholm and buenos aires.” As the USSR collapsed and the dictatorships of Latin America fell, Benedetti expressed the confusion so common to those who grew up in the dangerous yet neat, ordered, and simpler world of the Cold War, with two clear sides on a polarized planet: one good, one evil, regardless of which side one was on. In “Mulatto,” Benedetti saw himself “trapped in / a twofold mulatto nostalgia,” in a tunnel “where we yearn for what awaits us further on / and then we’ll yearn for whatever we’ve left behind / and we’d love to weep like the angels / or at least like they say the angels used to weep / before the death of ideologies.” Benedetti reflects on exile, however, with his determined optimism of the heart rooted in his pessimism of the mind (as Gramsci would put it) when he tells us that “I return to the exile that’s banished me / and then I feel like / I don’t belong / anywhere / to anyone” and affirms that “to be honest I’m not sure / what I’m doing here / but here I am.”

Witness ends with Benedetti’s recognition that his exile is an exile from the world, a world in which consumerism and capitalism seem to have gained the upper hand against the struggle for humanity. In “Che,” he writes of his hero that “they have turned him into consumer goods” and used “him as a postscript,” but this is a conclusion Benedetti is unwilling to accept. He continues his rebellion in the name of beauty against this ugly world to the last pages in “Outdoor Poems”:

Outdoor poems are made of cloud

each carries its snippet of universe

and if a bird flies in their words

that means the heart has opened its cage.

As an old man who remained a faithful poet and revolutionary to the end, even in the painful last years of his life, he maintained that “maybe happiness is nothing more / than believing we believe the unbelievable.” And perhaps that is Benedetti’s lasting gift: His humane vision allows us to believe the unbelievable to be possible.

Clifton Ross is a Berkeley-based writer and filmmaker. His book, Translations From Silence: New and Selected Poems (Freedom Voices Press, 2009), won the 2010 PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Award for Literary Excellence. It was published in Spanish in 2007 in Venezuela by Editorial Perro y Rana in the Poetas del Mundo Series.

Read the rest of NACLA's Fall 2012 issue: "#Radical Media: Communication Unbound."