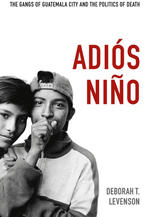

Deborah Levenson has described Adios Niño as the book she needed to write, but not the book she wanted to write. Similarly, we could argue that this is the book on gangs we need to read, but not the book we want to read. Adios Niño chronologically follows the development of the youth gangs (maras) of Guatemala and tries to explain their violent transformation through several successive stages of self-understanding. In a recent talk at NYU, Levenson admitted to being repulsed by her own book, but that only intensifies the power of her argument. She analyzes the historical effects of Guatemala’s social movements and military dominance, beyond just looking at the current situation of marginalization, on the development of the Guatemalan maras. The cover image of two street children, without the prison bars and tattoos normally associated with the maras, underscores Levenson’s desire to present an alternative story and argument for the maras’ historical present.

Adios Niño chronologically follows the development of the youth gangs (maras) of Guatemala and tries to explain their violent transformation through several successive stages of self-understanding. In a recent talk at NYU, Levenson admitted to being repulsed by her own book, but that only intensifies the power of her argument. She analyzes the historical effects of Guatemala’s social movements and military dominance, beyond just looking at the current situation of marginalization, on the development of the Guatemalan maras. The cover image of two street children, without the prison bars and tattoos normally associated with the maras, underscores Levenson’s desire to present an alternative story and argument for the maras’ historical present.

Her goal was to write the backstory of the present and show not only how the gangs developed in Guatemala, but the various ways something else could have happened. To do so, she follows the maras’ transformation into the hyper-violent gangs we see today through the parallel social transformations of the country.

She argues that the original maras back in the 1980s were part of a social imaginary of positive protest and a belief in hope and agency. Unfortunately, military prowess, civil war, and the long series of horrendous massacres suggested that violence was the dominant societal ideology. The maras in Guatemala today see death as a way to control life and are even proud of knowing they will die young and believing they have control over not only their own life, but also their death. This supremely violent and death-centric gang culture is a direct offshoot of the supremely violent death-centric military culture of the civil war. The gangs have shifted, as has Guatemalan society, from the hope found in the 1980’s radical movements to the necroliving of today where death dominates.

Adios Niño is a challenge to “presentism,” or the way that discussions of gangs so often fall into the trap of writing about the present—as simply the present—without discussing the path from the past. Levenson believes that this presentism includes dominant ethnographies that focus on multiple marginalities as an explanation for gang development. She argues that just looking at the frameworks of family dynamics or inequality or any such factors of the current environment in which gang members live, while important, fails to explain differences among gangs or why gangs form and transform. The transformation question runs through Adios Niño, which is organized chronologically to follow the gangs from their beginnings as cultural communities to their current-day violent formation. The early maras were “composed of fairly average urban youth who at the worst broke minor laws” and gathered to socialize or hold breakdance competitions, and framed their thievery as part of a sociocultural discourse challenging the bourgeoisie. Levenson’s previous research on the Guatemalan labor movement underlies an argument that the culture of social protest in the 1980s provided an alternative to the violence of today’s gangs.

As the 2013 trial of Ríos Montt for genocide shows, the effects of the civil war in Guatemala are far from over and Levenson’s book delves into the effects of the war on the transformation of the gangs. At a very basic level, the war created a multitude of orphans left without family or support system, and the maras recruited them. And these were war orphans, meaning that their lived experiences of violence contributed to their lived expressions of violence. State terror not only destroyed the family dynamic, but further decimated alternative forms of protest or organization and created a culture of violence and impunity. “The feisty 1980’s mareros are one unusual reminder of an era of social struggle. Those of the postwar period are part of the heritage of war, and they portend the permanency of the war in everyday life. Neither rebels nor conformists, they are orphans of the world, not only of Guatemala. They have been criminalized by adults … for all manners of evils.” Levenson’s discussion of the war at times relies on a montage of violent imagery without fully developing the connection between the civil war and the violent maras. Since this is one of the central points of her argument—that the political backstory of Guatemala specifically contributed to the transformation of these gangs—it would have benefitted from further analysis.

In a particularly powerful part of the book, she argues that the criminalization and demonization of the maras in their early stages contributed to the reification of the gangs as criminal and demonic. The media representation of the gangs, particularly through the evangelicals, presented these youth, back in the 1980s, as the dominant threat to Guatemalan society. The gangs were scapegoats for all forms of evil, and then became evil. The media paranoia gave birth to an externally created violent role that the gangs then expanded to fill: “mareros have been represented as threats to democracy, peace, toil, and the everyday life … attention has focused on the imaginary marero.” This demonization of marginalized youth is not isolated to Guatemala in the 1980s; it is equally relevant in New York City today. We need a better understanding of the effect of media demonization on the actual violence of young people.

The gangs are so complex that it would be impossible to cover every aspect of their formation and transformation. Thus, in many ways, Adios Niño asks more questions than it answers. What is the role of drugs and the transnational drug trade on the violent transformation of the maras in Guatemala? How did neoliberalism and the shifting political culture affect the gangs? How does Guatemala’s indigenous population and politics differentiate the maras in Guatemala from those in other parts of Central America? All of this, too, is part of the backstory of the present as we try to consider the myriad of other ways the gangs could have developed. And these are the questions we should be researching in Guatemala and elsewhere. I look at the “innocent” gangs of delinquents in Peru who sound a lot like the early 1980s maras Levenson discusses and wonder how they will be affected by the anti-mining protests, or the decline of the Sendero Luminoso, or the neoliberal expansion of Lima, or the increasing coca cultivation and drug trade in Peru.

Naomi Glassman has a BA in Latin American Studies from Swarthmore College and currently works as NACLA’s archival intern.

Read the rest of NACLA's 2014 Spring issue: "Mexico: The State Against the Working Class"