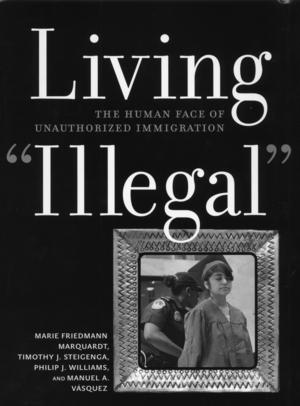

Living “Illegal”: The Human Face of Unauthorized Immigration

By Marie Friedmann Marquardt, Timothy J. Steigenga, Philip J. Williams, and Manuel A. Vásquez, The New Press, 2011, 328 pp., $26.95 (hardcover).

The authors of Living “Illegal” have made a significant attempt at humanizing an immigration debate that has lost all humanity in mainstream politics. They delve into the lives of ordinary migrants and paint a moving picture that defies the polarizing, hateful, stereotypical debates over immigration. Living “Illegal” sheds insightful light on what it means to live in the shadows of “America.”

The protagonists of Living “Illegal” are precisely those undocumented immigrants who were forced to leave their homes and are living on the margins of U.S. society. Vibrant and raw testimonies give depth to the faceless immigration debate, such as the story of Don Felipe, a migrant from Santa Ana, Mexico, who became a successful entrepreneur in Atlanta, or Claudia and Rita, who tell of their struggles as migrant women who crossed multiple borders and faced countless dangers from Guatemala through Mexico and into the United States. Claudia tells the authors:

The protagonists of Living “Illegal” are precisely those undocumented immigrants who were forced to leave their homes and are living on the margins of U.S. society. Vibrant and raw testimonies give depth to the faceless immigration debate, such as the story of Don Felipe, a migrant from Santa Ana, Mexico, who became a successful entrepreneur in Atlanta, or Claudia and Rita, who tell of their struggles as migrant women who crossed multiple borders and faced countless dangers from Guatemala through Mexico and into the United States. Claudia tells the authors:

“The biggest risk a woman takes in crossing [into Mexico] is being raped. Coming alone, it’s risky. You leave your house in your own town and there are people from other places, people you don’t know. I was the only woman in the group with twenty-two men. I prayed the whole time. I wasn’t thinking of myself, but of my daughters.”

Through engaging with personal testimony, the reader gets a clear and poignant portrait of the tremendous sacrifice and extraordinarily difficult journey north, which hundreds of thousands of people endure annually. Unauthorized migrants also describe the harsh realities they face once in the United States, living an underground life of invisibility, fear, and stress.

National and local immigration policy has only exacerbated the hardships they face. In one case, covered in Chapter 3, “Living Together, Living Apart,” the Cobb Country, Georgia sheriff’s office implemented the 287(g) program, which permits state, local, and county law enforcement agencies to work with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to investigate people’s immigration status. Many undocumented migrants live in such fear of being deported that they do not report crimes and become targets of assaults and robberies. Wage theft, in which employers hire day laborers and refuse to pay them, is common across the United States. The authors quote a Mexican migrant and resident of Cobb County discussing policies like 287(g):

“A lot of people are scared. I noticed that a lot of people have moved, they’ve moved to other towns where there aren’t these types of detentions.”

The book also points to how the mainstream has tied the terms Latino and illegal to criminality. Yet despite the unfavorable public discourse, unauthorized immigrants are more likely to be the victims of crime, not the perpetrators. Living “Illegal” documents a 2004 incident in Georgia in which four high school students picked up a 54-year-old day laborer and attacked him, stole $260 from him, and left him beaten in a pool of blood. The authors explain that this was not an isolated incident.

They further note that the FBI reported a 40% increase in hate crimes against Latinos across the southeastern United States since 2003, and that in 2009, a poll of Latinos living in the South conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that 68% reported having suffered racism in their daily lives.

By bombarding the public with rhetoric that blames migrants for social problems such as unemployment, the economy, crime, and the cost of public benefits, mainstream media and politicians encourage violence against immigrant communities. In other words, living “illegal” means living stigmatized and discriminated.

The book also provides a larger context to the personal stories, arguing that migration isn’t just caused by “push factors” like poverty, unemployment, and political turmoil, or “pull factors” like wealth or job opportunities. Instead, the authors explain, people’s decisions to migrate are strongly shaped by changes in U.S. immigration policy and U.S. economic needs. The book analyzes how slavery, the Chinese Exclusion Act, World War II, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the overthrow of democratically elected presidents of Latin America, military interventions, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, and other factors have set the stage for migration patterns and increasing numbers of unauthorized immigration.

Many migrants do not just magically appear out of nowhere, write the authors, but “come to specific destinations in the United States because our economy creates a large demand for people to mow our lawns, clean our dishes and bathrooms, work bottom-end construction jobs, and fill a niche of other service and short-term labor needs.”

In other words, the U.S. need for a constant source of exploitable cheap labor has principally guided immigration policy.

“By establishing quotas and suspending the Bracero Program, new laws ensured that Mexicans, and also Central and South Americans, who desired to work in the United States, had to seek alternative ways to enter, even though work opportunities were available. Thus began the era of unauthorized migration from Latin America,” write the authors.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government has continued to intensify the same hardline immigration policies, regardless of who is in the White House. For instance, in 2004, under the Bush administration, the total budget for immigration enforcement was $9.5 billion. By 2010, under the Obama administration, this had escalated to $17.2 billion. Living “Illegal” emphasizes that over the last four years, the Obama administration has deported record numbers of undocumented immigrants, increased the Homeland Security budget like never before, and implemented programs such as 287(g) and Secure Communities (a collaboration between the police, the FBI, and ICE to share immigration databases) nationwide. It has continued to militarize the U.S.-Mexico border, causing increasing deaths to migrants trying to cross into the United States. More undocumented detainees are being held at for-profit detention centers, and the Obama administration failed to pass the DREAM Act and the elusive Comprehensive Immigration Reform.

Despite the dark political landscape, Living “Illegal” closes on a positive note, examining the churches and communities that support migrant communities across the United States. Luz del Mundo, a church in Atlanta, for example, serves as a place where migrants find mutual support and build community. At St. Thomas the Apostle of Cobb County, Georgia, congregation members responded to the serious illness of an undocumented immigrant by pooling their own resources, and with the help of the church, were able to help pay for his medical expenses. The church also provides immigrants with referrals to services that can provide for their basic needs with employment, food, housing, and legal issues.

The authors portray these churches as a pivotal safe space for migrants, where diverse communities—both immigrant and non-immigrant—engage in meaningful dialogue and where “transformed relationships can serve as the foundation for broad social, economic, and political change.”

The book ends with a chapter titled “Migrants Mobilize,” which highlights how migrants are themselves agents of social change. The authors describe the process the people of the city of Jupiter, Florida, courageously opened El Sol Neighborhood Resource Center to support day laborers in their community. In Alterna, Georgia, a small intentional Christian community has developed, which can serve as an inclusive model of living cross-culturally.

The book also highlights the Trail of Dreams, organized in 2010, in which four young adults, Juan, Felipe, Gaby, and Carlos, walked from Miami to Washington, D.C., to bring attention to the plight of the 1.8 million undocumented students fighting for access to education and legalization. Carlos tells the authors:

“We did it because as undocumented individuals we wanted to share our stories with our own voices. For too long people have told our stories incorrectly. We did the walk because we wanted to end the nightmare of racial profiling programs, such as 287(g), and we wanted the DREAM Act to pass.”

Overall, Living “Illegal” offers an important, painful, poignant, and empowering portrait of the people who live in the United States not only “illegally,” but also with dignity, resilience, and the determination to make strides toward justice and equality for all. Despite a hostile, oppressive political and economic system, migrant communities are working, building grassroots political power, and enriching their vibrant neighborhoods. Living “Illegal” documents both a harsh political landscape and a beautiful reality of struggle, solidarity, and resistance.

Raúl Alcaraz Ochoa was born in Jalisco, Mexico, and grew up in Richmond, California. He has organized around educational justice, youth power, queer justice, and migrant rights issues. He currently lives and organizes in Tucson.

Read the rest of NACLA's Fall 2012 issue: "#Radical Media: Communication Unbound."