Mexico recently passed a labor law that will make jobs less secure by, among other things, permitting greater outsourcing as well as temporary and part-time work. The law is the result of 40 years of struggle among political parties, rival unions, employers, and workers. While the new law represents a defeat for the Mexican working class, the struggle by Mexican unions and their international allies continues.

Mexico’s labor law reform has its origins in the economic crisis of 1982, when the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and large creditor banks began to exert pressure on Mexico to carry out a thoroughgoing liberal economic reform. First, the technocratic wing of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and then the National Action Party (PAN) initiated a series of proposals, including constitutional amendments, changes in law, and the signing of international agreements designed to open Mexico to greater international trade and more foreign investment. The most important of the international agreements were Mexico’s entry into the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) in 1986—replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995—and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Attempts by the nationalist wing of the PRI to defend the protectionist economic system failed, leading, in the late 1980s under President Salinas de Gortari, to the deregulation and privatization of much of Mexico’s state sector. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, foreign corporations and Mexican capitalists rapidly expanded their investments in Mexico both in the largely union-free maquiladora free-trade zone on the northern border and in the new industrial zone about 200 miles to the south.

The Mexican Employers Association (COPARMEX) began to lobby for a new labor law in the 1980s. The

basic idea was to reduce government and union interference in industrial relations and in the workplace so as to increase flexibility, that is, the employer’s ability to use workers as they wished. Employers saw this as a necessity because Article 123 of the Mexican Constitution of 1917, the most advanced in the world at the time it was written, and the Mexican Federal Labor Law of 1931 as subsequently amended in the 1970s, had strong protections for labor unions and workers. They recognized the rights to organize, bargain collectively, and strike, established profit sharing, and protected job security by prohibiting the hiring of workers on an hourly basis, banning virtually all subcontracting, and by severely limiting causes for discharge.

COPARMEX wanted to break the power of the unions, but it’s important to understand that there are various sorts of unions in Mexico. Dominating the union sector are corporatist or state-controlled unions, historically affiliated with the PRI and organized in the Congress of Labor (CT) mainly as the Confederation of Mexican Workers (CTM). There are also company unions like the National Federation of Independent Unions (FNSI), created by the employers of Nuevo Leon in 1936 and for a long time restricted to that state, but recently expanding to half of the country’s 32 states. Finally, there are the genuinely independent formations that are controlled neither by the government nor by the employers, such as the National Union of Workers (UNT), which was formed in 1997 by independent unions such as the Authentic Labor Front (FAT) and others that had left the Congress of Labor, as well as unions such as the Miners and Metal Workers (Los Mineros) and the Mexican Electrical Workers Union (SME), which now operate independently. Since the 1940s, government officials, employers, and the “official” unions have colluded to prevent strikes, keep down wages, and to fire workers who stood up for their rights all for the purpose of encouraging foreign investment. While the corporatist unions had been authoritarian, corrupt, and violent since the late 1940s, by the 1990s many had become thoroughly gangsterized, selling employers “protection contracts” with no more than the legal minimum wage and conditions negotiated without the knowledge of the workers. Somewhere between 80% and 90% of all contracts were estimated to be of this sort by the 1990s.

While some employers found a way to work around the system by entering into protection contracts with official or company unions, others simply ignored the law and began to hire and fire, to outsource and subcontract as they saw fit. But virtually all employers wanted to do away with the restrictions of Article 123 and the Federal Labor Law, and supported the unsuccessful efforts of COPARMEX in the 1980s to make it harder for unions to organize and to strike, while also removing protections for unions and workers.

In 1995, Nestor de Buen, a highly respected labor lawyer, drafted a labor law reform proposal. Although put forward in the Senate by the conservative PAN, de Buen’s proposal was not simply a pro-business bill. In fact, it was inspired in part by Spain’s labor law and by International Labor Organization standards and language, and incorporated ideas emanating from independent unions as well as management.

De Buen called for a new labor relations system for Mexico in the “globalized” world. He offered employers a system that would give them more productivity, and offered workers greater transparency along with a system of union and contract recognition that would give them more democracy and potentially more power. His proposal failed because it did not please the employers who wanted productivity but feared workers’ democracy and power. It did not please union officials who feared losing government backing. And it did not please workers who did not want to give up historic protections to increase productivity for their employers.

During the presidency of Ernesto Zedillo (1994-2000), the center-left Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) put forward its own reform proposal incorporating many of de Buen’s suggestions, such as independent labor judges (who are not institutionally biased against independent unions) and a simpler process for union and contract recognition. The proposal attempted to preserve many of the historic labor protections, while also making some concessions to employer demands for productivity, and putting some limitations on the right to strike. With a minority of deputies in the Congress, and opposition from both the PRI and the PAN, the PRD proposal died.

*

The introduction of a subsequent proposal by the PAN in January of 2003 spoke of the need to be a modern, competitive nation, and of a new dynamic in labor relations. Notwithstanding the lofty phrases about mutual collaboration and interest, the substance of the proposal represented an attempt to strengthen state control over unions while extending more power to employers, and at the same time eliminating worker rights and protections. De Buen’s suggestions were gone. Despite a rhetorical flourish in the direction of the democratic unions, not only were his proposals ignored or eviscerated, but onerous new prerequisites were added, making it virtually impossible for workers to change unions, to create or join an independent union, or to strike.

Faced with major opposition, PAN’s Secretary of labor Carlos Abascal Carranza opened negotiations regarding labor law reform. However, on November 25, 2004 the PRI and CTM suddenly announced an agreement to move forward on what was known as the Abascal Plan. The law was resisted strongly by the independent unions and their international allies. However, there were various perspectives on the best way to oppose the proposal. A group of unions representing workers in state industries who had enjoyed a rather privileged status and were not facing the difficulties of organizing new groups of workers strongly opposed any changes. They argued that the problem was lack of enforcement, and that to propose any changes could open a Pandora’s box, potentially leading to something worse. The UNT took a more aggressive stance. Its proposals, introduced by the PRD, called for the right of workers to know if they had a labor union and to have access to the union constitution, by-laws, and contract. They also called for the abolition of the tripartite labor board—which historically colluded against independent unions—and for their replacement by independent labor tribunals.

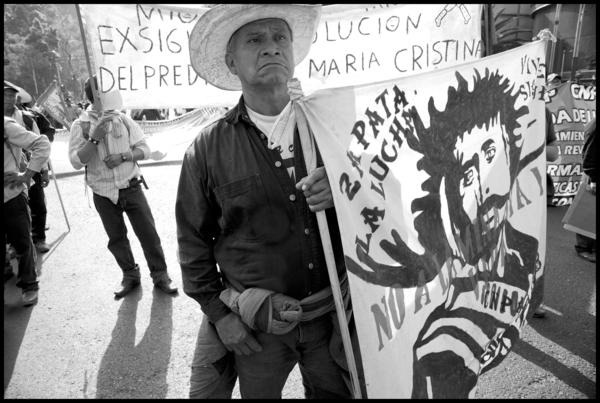

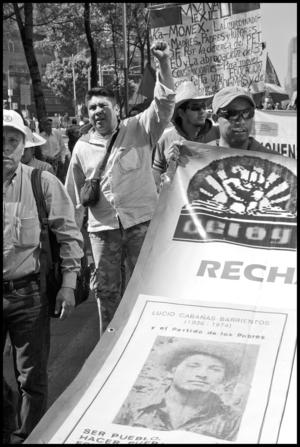

Labor and social movements responded rapidly, beginning a sit-in at the Chamber of Deputies on December 1, and calling for major mobilizations in Mexico City and around the country. They also called for international opposition. Faced with threats of major mobilizations, the proponents announced that introduction would be delayed until Congress reconvened in February.

In the interim, unions from Mexico, Canada, and the United States, along with the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), filed a submission with the U.S. Department of Labor alleging that the Abascal Project violated the central obligation of the NAFTA labor side agreement (NAALC), which obligates the parties to ensure that its labor laws provide for high labor standards. Human Rights Watch also condemned the proposal and Representative Marcy Kaptur (DOH) began circulating a congressional sign-on letter to Labor Secretary Elaine Chao, urging that she accept the submission, review the Abascal Project, and immediately initiate consultations with the Mexican government to address its violation of Mexico’s obligations under the NAALC. The combination of worker mobilization in Mexico and international solidarity succeeded in keeping the law in committee. Although rumors circulated in subsequent years, it was not until 2012 that labor law reform moved forward.

Meanwhile, the attack on labor escalated. Felipe Calderón’s administration, best known for its disastrous drug wars, also waged a war on workers, particularly the SME, liquating Central Light and Power, the public company in which most of its members worked, occupying plants, sweeping aside the union, and firing 44,000 employees. Calderón also cooperated with the Grupo Mexico mining company to eliminate Los Mineros from the Cananea mine and to force the union’s national president into exile in Canada. The situation for workers became disturbingly worse, with legitimate trade union and social movement leaders facing violence, intimidation, and criminal charges on top of the intransigence and the usual collusion between the labor boards, employers, and official unions. All of this taken together, combined with the economic recession of 2008, strengthened the hand of the conservatives and weakened the hand of labor.

In accordance with new political reforms permitting the designation of two bills under fast track, and working with President Calderón, the Mexican legislature introduced labor law reform in September 2012. After many revisions, both houses passed a somewhat modified version of the COPARMEX proposal in November, even before the new president, Enrique Peña Nieto, took office.

The new law gave management labor flexibility—part-time and temporary work, pay by the hour, probationary and training periods—and brought Mexican law in line with international standards on discrimination, sexual harassment, and flexibility for working women, while making a small concession in the area of workers’ rights by calling for the publication of collective bargaining agreements. [See box for the law’s principal points.]

The independent unions that opposed the law succeeded in eliminating some of the worst provisions in terms of restrictions on freedom of association prior to passage, a remarkable accomplishment that still leaves a tiny space within which independent unions can operate. However, the new law did not deal with protection contracts, which are perhaps the most serious problem facing Mexican unions. The employers, however, who had been promoting a neoliberal vision of legal, unrestricted outsourcing, were far from pleased with the restrictions that were imposed on sub-contracting. The independent unions, leftist political parties, and their allies have vowed to continue the fight both in the courts and in the streets.

*

Fighting for survival in a hostile political climate and a depressed economy, unions organized the Tri-National Solidarity Alliance (TNSA) which is composed of most of the significant labor organizations in Mexico, Canada, and the United States, an important development in all of the countries. For the past three years, unions and their allies have organized a week of action in solidarity with the independent unions in Mexico, targeting embassies and consulates in as many as 50 countries around the world.

These actions laid the groundwork for steps taken by the global union IndustriALL, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), and the Latin American Union Confederation (CSA). The groups followed up on an International Labor Organization (ILO) case that had been filed by IndustriALL and the Mexican Telephone Workers, Los Mineros, the Union of the Autonomous Metropolitan University of Mexico, and the FAT’s metal workers union (STIMACHS), and had resulted in strong recommendations regarding protection contracts.

In an August 2013 meeting with President Enrique Peña Nieto and Labor Secretary Alfonso Navarrete Prida at the Los Pinos Presidential Palace in Mexico City, the government conceded that protection contracts were an issue and agreed to consult with the ILO Director General regarding a technical review of the labor laws. The Peña Nieto administration also agreed to work towards a resolution of the dispute involving SME, stated that the General Secretary of Los Mineros was free to return to Mexico, and said it would take steps to ratify ILO convention 98 that protects the right to bargaining collectively. These statements represent rare government recognitions of labor rights and even rarer promises to do something about them. However, there is little reason to hope for positive change from a government that has clearly demonstrated its commitment to pursue neoliberal policies and to attract foreign capital.

While the Mexican unions continue to wage an uphill battle, and the Tri-national and other labor initiatives are significant, the Mexican independent labor movement is weaker today than at any time in the last 25 years. What Mexican workers need if they are to overturn the labor, education, and other regressive reforms is a rank-and-file movement among workers across sectors, industries, and unions with the economic power to really disrupt private sector production and profits, together with a mass political movement for a democratic socialist alternative. We have yet to see such a movement emerge.

Robin Alexander is Director of International Affairs for the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE). Dan La Botz is a teacher, writer, and activist. He is the editor of Mexican Labor News and Analysis.

Read the rest of NACLA's 2014 Spring issue: "Mexico: The State Against the Working Class"