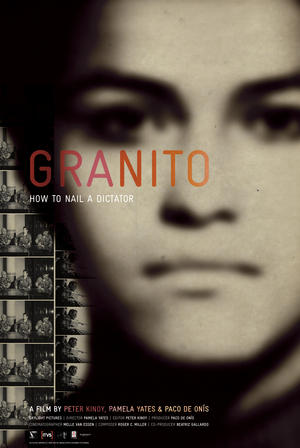

Granito: How to Nail a Dictator directed by Pamela Yates and produced by Paco de Onís, 2011, 103 mins., Skylight Pictures (skylightpictures.com)

For activists trying to halt U.S. intervention in Central America during the 1980s, Pamela Yates’s documentary film about Guatemala, When the Mountains Tremble (1983) was obligatory viewing. It chronicled Guatemala’s “hidden war,” a brutal 1982 counterinsurgency that leveled hundreds of Maya villages and killed tens of thousands of people. A United Nations truth commission in 1999 called these army massacres a genocide. The wrenching scenes of state violence and indigenous resistance in When the Mountains Tremble affected me greatly as a college student in the 1980s; partly through this film, as Yates describes for herself, “Guatemala wrapped its arms around my soul and would never let me go.”

For activists trying to halt U.S. intervention in Central America during the 1980s, Pamela Yates’s documentary film about Guatemala, When the Mountains Tremble (1983) was obligatory viewing. It chronicled Guatemala’s “hidden war,” a brutal 1982 counterinsurgency that leveled hundreds of Maya villages and killed tens of thousands of people. A United Nations truth commission in 1999 called these army massacres a genocide. The wrenching scenes of state violence and indigenous resistance in When the Mountains Tremble affected me greatly as a college student in the 1980s; partly through this film, as Yates describes for herself, “Guatemala wrapped its arms around my soul and would never let me go.”

Yates’s new film, Granito: How to Nail a Dictator, takes us back to those days. Yates says she began the Granito project several years ago when a lawyer investigating the genocide asked if her footage from Mountains might contain evidence that could be used in a trial against the high-ranking military officers blamed for the killing. For a quarter-century, Yates’s old cans of 16mm film had sat in storage; now those reels would be unpacked and scrutinized to see whether any of the outtakes might be useful in building a court case. In making Granito, Yates takes us on a journey from the highlands of Guatemala to an excavated cemetery in Guatemala City, to New York, Washington, and Madrid, and back again to Guatemala. The film chronicles what University of Georgia professor Amy Ross calls the complex “geographies of justice” that link diverse places and people in a decade-long effort to “nail a dictator”—in this case, former de facto head of state General Efraín Ríos Montt (1982–83), accused of orchestrating the Guatemalan genocide.

The timing of this film’s release could not have been more propitious. On June 17, the very day the film opened at the Human Rights Watch film festival in New York, news broke in Guatemala of the arrest of a general on charges of genocide. Although Ríos Montt has thus far eluded arrest and prosecution, his subordinate, 81-year-old retired general Héctor Mario López Fuentes, army chief of staff from 1982 to 1983, is now in custody in Guatemala awaiting trial, along with several other high-ranking army officials from that era. This is the first time anywhere in the world that a genocide trial is occurring within the national courts in the country where the crimes were committed. Granito doesn’t take us up as far as the current genocide trial inside Guatemala, but it narrates the uncovering of forensic, testimonial, and archival evidence that led to it. The tale is gripping, moving, inspirational, and informative.

Granito weaves back and forth from 1982 to the present by juxtaposing original footage from When the Mountains Tremble with documentation of the genocide investigation. Just as Mountains was held together by the testimony of a then little-known Rigoberta Menchú, who had escaped Guatemala and was living in exile, the thread that ties the different facets of Granito together is the story of Pamela Yates herself. Yates recounts how she arrived in Guatemala in early 1982 as a young filmmaker who thought she could help stop the violence by documenting it. In those final bloody weeks of the dictatorship of General Romeo Lucas García, Guatemalan journalists faced mortal danger, and there were relatively few foreign journalists in the country, possibly because Guatemala was seen as a place where the United States was less involved than neighboring El Salvador and Nicaragua (even though the United States had been deeply engaged in Guatemalan counterinsurgency ever since the CIA-orchestrated coup in 1954). Fewer still were the reporters who ventured out into the rural areas that were becoming the killing fields for the military’s attack against the presumed support base of the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG), which according to army documents of the era included “100 percent” of the population in certain regions.

Scheduled presidential elections in early 1982, however, created a small opening for the international press corps to cover Guatemala (the elections, held on March 7, were widely seen as fraudulent; two weeks later, a military coup brought Ríos Montt to power). The army was keen on persuading the U.S. Congress to resume military aid that had been interrupted under President Carter because of widespread human rights abuses. In this context, Yates was able to begin filming in Guatemala.

Yates eventually meets el mero macho, army chief of staff Benedicto Lucas García, brother of the soon-to-be-deposed president. She asks to go along on an army helicopter mission. “He took one look at my innocent face and must have thought, ‘Hey, why not have this gringita come along, what harm could she possibly do?’ Little did he know that what I was about to film would become evidence against him 25 years later.” In a dramatic moment, a guerrilla sharpshooter shoots the helicopter down; both Lucas García and Yates survive the crash, and, according to Yates, the general saw the incident “as a test of my mettle, and in his eyes I had earned the right to go out with the army on their field operations.”

At first, I wondered if Granito would be another example of what Argentine sociologist Elizabeth Jelin calls the “ritualized repetition of the traumatic and sinister story.” At the beginning of the film, images of a death-squad kidnapping on the streets of Guatemala City and charred houses and unmarked graves in the highlands are paired with a voice-over by Menchú from the original Mountains: “The only thing we have is our destiny of pain, suffering, and misery.” Representing historical memory in Guatemala is complicated, and equating collective memory with histories of death has a lot of narrative power, for understandable reasons: The brutality was extreme, and the revolutionary movement failed spectacularly. From the vantage point of the present, it is hard to excavate through the grim layer of violence to get a deeper sense of what motivated people’s struggles. Yet the problem with this conflation of historical memory with violence and death is that it elicits sympathy rather than empathy, insofar as it drains people of their identities as protagonists of history and reduces them to a flattened category of “victim.”

But as I watched more of Granito, these concerns dissipated. Above all, this film is about protagonism. The film takes its title from the idea of many different people putting their own small grains of sand together to create larger, meaningful change. The film is multilayered: It traces Yates’s own personal odyssey and the work of an international human rights team (a group of smart, savvy, and committed women who recall Guatemalan writer Francisco Goldman’s apt term, “the sweet sisters of solidarity”). Granito also illuminates the great, indeed, heroic efforts of survivors, community organizations, lawyers, and forensic specialists in Guatemala who not only document the genocide but also pursue justice for its victims, even when it is arduously slow and harrowing.

An outstanding feature of Granito is how it takes us back to the “insurrectional moment” of the early 1980s, before the scorched-earth army sweeps laid waste to large swaths of the Maya highlands. The film does this by interspersing Yates’s original footage with a retrospective interview with Naomi Roht-Arriaza, a University of California–Hastings law professor who was a journalist in Guatemala in 1982 and who had helped Yates gain access to a guerrilla encampment in the mountains. Yates also tracks down Gustavo Meoño, the Guatemalan guerrilla commander who authorized her 1982 meeting with the alzados, the URNG rebels.

Both Roht-Arriaza and Meoño describe the intensely charged political atmosphere in Guatemala in the early 1980s, when the entire Central American region was in ferment. The Sandinistas had taken power in Nicaragua, and there was a sense that the revolution could triumph in El Salvador and Guatemala as well. No one imagined the scale of the repression that was to come. “It seems funny to talk about it now,” Roht-Arriaza reflects, “but the word that comes to mind is hope. People had a lot of hope that things really could be different.”

In one of Granito’s early scenes, we are transported back in time to Roht-Arriaza and Yates’s January 1982 meeting with a group of Maya villagers aligned with the revolution. Roht-Arriaza recalls: “We expected 15 people to show up. . . . 10 to 15 people showed up, then 50 people, then 100 people, then 200 people. In a way it was kind of magical; it was this clearing in the woods, literally in the middle of nowhere, and all of a sudden it was full of people. A half hour before there had been nobody, and a half hour after it ended, there was nobody again.”

During this meeting, which first appeared on film in When the Mountains Tremble, guerrilla combatants spoke in K’iche’ about their hopes for change in Guatemala. It is a haunting scene: Just three months later, this region would be one of the hardest-hit by the counterinsurgency, with numerous villages destroyed. Most likely some of the people who gathered in that clearing did not survive.

It is beyond the scope of Granito to explore the complexities of what participating in the revolution meant for people. As noted in the film, the question of whether there was an authentic insurrection or whether Mayas were “deceived, manipulated, or caught between two fires” is a subject of ongoing (although mostly spurious) debate in Guatemala. Meoño argues that there was an insurrectional moment (elsewhere he recalls this scenario as a “vortex,” whereby in some cases the guerrillas intensified the armed struggle, while in other cases rural populations joined the rebels so quickly that they overran the insurgents’ organizational structures).1 Given the disastrous outcome of the guerrilla struggle, it is not surprising that today this history of revolution is often disavowed. One of Granito’s most stirring contributions, therefore, is to remind us of a time before the massacres, a fleeting moment when hundreds of thousands of people in Guatemala deposited their hopes in a belief that broad social change was possible.

The main story Granito tells is about reckoning with Guatemala’s repressive past. In 1999, the Commission for Historical Clarification (CEH), Guatemala’s truth commission mandated by the peace accords and run by the United Nations, issued a 12-volume report on the history of the conflict, calling the destruction of Maya communities “acts of genocide.” The term is significant, since genocide is not covered under the amnesty laws that were passed as a prelude to the peace accords. The crime of genocide can be prosecuted in Guatemala, but until this year, the country’s Justice Department (Ministerio Público) had not wanted to touch the cases.

This is where the geography of justice gets complicated. Within Guatemala, the Center for Legal Action on Human Rights (CALDH), a human rights NGO, presented genocide cases that languished in the national courts for a decade. Parallel to this, a genocide case was presented in Spain under the concept of universal jurisdiction—the idea that some crimes are so heinous that they can be prosecuted anywhere, regardless of where the crimes were committed. Spain had already dealt with the concept of universal jurisdiction in the famous case against former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in the late 1990s. For several years, Spanish courts deliberated over whether or not to hear the Guatemalan genocide case. Finally, in 2005, the Spanish high court opened the way for a genocide prosecution, and in 2006, Spanish human rights lawyer Almudena Bernabeu, who co-narrates Granito, took over as lead counsel.

As Bernabeu explains, genocide is a difficult crime to prosecute. In order to prove genocide, the legal team would have to show that the Guatemalan army intentionally killed Mayas as Mayas. According to the CEH, which drew upon emerging international jurisprudence to make its genocide argument, the intention to commit genocide did not have to be explicitly expressed; rather, it could be inferred from the army’s “general political doctrine” of annihilation against the guerrillas and perceived supporters, combined with the “repetition of destructive and discriminatory acts,” such as killing children and elderly people and razing entire Maya villages. The army’s ultimate motivation was to defeat the insurgency, but in order to do this it intentionally killed Mayas, at least in certain regions, because the military high command viewed these indigenous populations as such as inherently subversive and as “internal enemies.” The CEH report helped shape the legal case in Spain, even though the truth commission’s mandate prevented it from assigning individual responsibility for the genocide.

To “nail” Ríos Montt on charges of genocide, the legal team would have to show that he had given the orders for the sweeps and that he knew what his men were doing in the field. The team would have to build its case on the logic of command responsibility. Yates’s film outtakes prove important to this effort: In a July 2, 1982, interview with Ríos Montt, the general told her that the Guatemalan army’s greatest strength was the vertical control exercised by those at the top of the command structure. Ríos Montt said he controlled the entire army, that he gave the orders.

But the team also had to show that the army high command knew about the atrocities being committed as part of the counterinsurgency. In its ongoing detective saga, Granito takes us to the offices of the National Security Archive, an NGO in Washington, D.C., where forensic archivist Kate Doyle reveals a previously secret Guatemalan military document called Plan Sofía. Plan Sofía is a collection of army dispatches documenting a counterinsurgency sweep in the Ixil region of El Quiché in July and August 1982. The mission is “extermination” of subversive elements in the area, which the army describes as “every village.” The dispatches are significant because officers in the field created them to show their superiors that they did what they were told. “Plan Sofía shows a two-way flow of information,” Doyle notes, “a constant coordination between the high command and the patrols on the ground.”

Bernabeu agrees: “When we confront Ríos Montt with this evidence, there is no way he will escape. I think it will change Guatemala forever.”

Granito shows us as, one by one, people come forward before the judge in Spain to testify about the Guatemalan genocide. Yates arrives with the 1982 film outtakes from When the Mountains Tremble. Maya K’iche’ villagers from the embattled community of Ilom, high in the mountains of northern El Quiché, describe the horrors of what they experienced in 1982. Freddy Peccerelli, a Guatemalan forensic anthropologist who grew up in the Bronx in the 1980s when his family was in exile there, testifies about the exhumation of clandestine graves in the highlands and what the bones recovered from these graves reveal about responsibility for the killings.

The evidence is solid. But there can be no trial unless Ríos Montt is extradited to Spain, and that remains the Achilles’ heel of universal jurisdiction. “When you fight impunity,” Yates observes, “impunity fights back.” Guatemala has thus far refused to extradite Ríos Montt, effectively halting the Spanish case.

But that is not the end of the story. The international process had a positive impact on Guatemala’s internal justice system; as Granito shows, the Spanish case helped motivate judges and prosecutors in Guatemala to take up human rights cases in the national courts. Although not shown in the film, the appointment in December 2010 of human rights attorney Claudia Paz y Paz Bailey as Guatemala’s first female attorney general was like moving a whole mountain of granitos, as the Ministerio Público suddenly began to investigate and prosecute major cases from the Ríos Montt era, demonstrating that the Guatemalan justice system can work when there is sufficient political will.

The highest-level case by far is the upcoming genocide trial in Guatemala, which focuses on the Ixil region of northern El Quiché. This case bundles several members of Guatemala’s military high command from the early 1980s, including López Fuentes, former intelligence chief and retired general José Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez, and the army’s former operations chief, General Luis Enrique Mendoza García. In a startling development, on October 12, an arrest warrant was issued for retired general Óscar Humberto Mejia Victores in the same case. Mejía Víctores had been Ríos Montt’s defense minister, and he later led a coup against him, ruling as Guatemala’s military president from 1983 to 1986. At the end of October, however, the 80-year-old Mejía Víctores was found unfit to stand trial after apparently suffering a stroke. For the time being, Ríos Montt benefits from legislative immunity from prosecution within Guatemala, ever since he was elected to a seat in Guatemala’s Congress. But his term expires in January 2012, and Guatemalan prosecutors have suggested that Ríos Montt may then face an indictment on similar charges of genocide and other war crimes.

Granito shows us other human rights initiatives underway in Guatemala. We are taken to Guatemala City’s La Verbena cemetery, where a team of forensic anthropologists is excavating a clandestine gravesite in which the bodies of many of Guatemala’s 40,000 “disappeared” were dumped. The body pit at La Verbena is so deep that it looks like one of the city’s infamous sinkholes. As Peccerelli describes, “This was a very well thought out system to disappear bodies, one of the few things that works in this country.”

We are also taken on a tour of the newly discovered police archives in Guatemala City, a cache of millions of police files from the era when police units acted as official death squads, which human rights groups hope will shed light on the fate of the disappeared. Meoño directs the project to recover the archives and make them available to prosecutors, and he tells us that the files are having a concrete effect on judicial processes in Guatemala.

One of Granito’s most emotional scenes is a tearful interview with Alejandra García, a daughter of human rights leader Nineth de García and Edgar Fernando García, a trade unionist kidnapped by security forces in 1984 and never seen again. The young woman, now a human rights lawyer in Guatemala, speaks about how her father’s disappearance darkened her childhood and how much she longs for information on his fate. In the film’s epilogue, we learn that in 2010, based on information gleaned from the police archives, two former policemen were convicted and sentenced to 40 years in prison for that kidnapping. Edgar Fernando García’s remains have yet to be found, however.

As Granito explores the meaning of these long-dormant cases, it shows us how the torch is passing to a younger generation of human rights activists in Guatemala. Many of the film’s Guatemalan protagonists, such as Alejandra García, Freddy Peccerelli, and Antonio Caba Caba, a leader of Ilom’s Maya K’iche’ Association for Justice and Reconciliation, were children during the worst years of the repression, and they are now leaders in the struggle for accountability. In the excavation and police archives projects, young technicians work alongside the older generation of political activists (although the film does not explore the potential disjuncture of these encounters). In one of Granito’s inspiring final scenes, Yates travels to Ilom for a screening of When the Mountains Tremble. The audience is filled with young people, who perhaps for the first time are seeing images of what their parents endured. As Meoño says, it is now up to these young people to recover Guatemala’s past and protect its future.

Like its predecessor, Granito is obligatory viewing for anyone interested in the human rights struggles of Guatemala and the legacy of the Cold War in Latin America more broadly. As Kate Doyle of the National Security Archive argues, the genocide in Guatemala, “how it looked and how it smelled,” was fundamentally a Guatemalan project, rooted in the country’s historic racism against the Maya. But the United States “was present at the creation of what became a uniquely savage counterinsurgency,” she says, helping to “create the machine which would go on to commit the massacres.”

“And that’s the responsibility that we bear,” Doyle adds. The reckoning, then, is not only for Guatemala.

As of this writing, it looks fairly certain that a former general and veteran of the counterinsurgency war, Otto Pérez Molina, will become Guatemala’s next president. There is a vein of despair in Guatemala that the struggles to recover historical memory perhaps make little difference. Yet, in a final scene, forensic anthropologist Freddy Peccerelli, who continues to receive death threats, tells us, “I think what we started here is a process, a process that is now being fueled by thousands and thousands of families, who are not going to be scared anymore, who are not going to be pushed into being quiet anymore.”

And so the work of the granitos goes on.

Elizabeth Oglesby is Associate Professor of Latin American Studies and Geography at the University of Arizona. She is editor, with Greg Grandin and Deborah T. Levenson, of The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Duke University Press, 2011).

1. Carlota McAllister, “An Indian Dawn,” The Guatemala Reader: History, Culture, Politics, Greg Grandin, Deborah Levenson, and Elizabeth Oglesby (Duke University Press, 2011), 352–60.

Read the rest of NACLA’s November/December 2011 issue: “Latino Student Movements.”