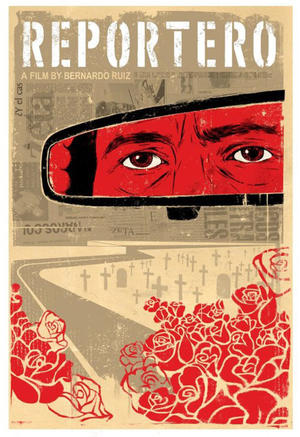

Reportero (Reporter) Directed by Bernardo Ruíz 2012, 72 mins. reporteroproject.com

When Mexican journalist Héctor Félix Miranda was killed on April 20, 1988, several thousand gathered in Tijuana to protest. They marched through the business district and amassed outside of the funeral home where the journalist’s body lay. They chanted angry slogans and carried banners that called for the resignation of the governor of Baja California, Xicoténcatl Leyva Mortera. The protesters wore black ribbons pinned to their lapels or waved black scarves.

Miranda’s body had been found that morning slumped inside of his blue 1981 Ford LTD. He had been shot several times in the neck and torso. The journalist was the author of the political satire column Un poco de algo (A Little Bit of Something), which was widely read in Mexico and printed in the Tijuana-based weekly newspaper Zeta, which he co-edited with Jesús Blancornelas.

Miranda’s body had been found that morning slumped inside of his blue 1981 Ford LTD. He had been shot several times in the neck and torso. The journalist was the author of the political satire column Un poco de algo (A Little Bit of Something), which was widely read in Mexico and printed in the Tijuana-based weekly newspaper Zeta, which he co-edited with Jesús Blancornelas.

Twenty-four years later, things still look very bleak for Mexican journalists. Reportero (Reporter), a documentary directed by former NACLA staff member and documentarian Bernardo Ruíz, exposes years of government corruption in Mexico that led to violence against Mexican journalists in the 1980s and more recent drug war violence against the media today. The film begins with a voiceover of recent news reports from Mexico that could evoke the perils of reporting during both periods: “A journalist was killed by multiple gunshots . . . Two women journalists were strangled and their naked bodies thrown in the street . . . Today a reporter murdered by an armed group was buried.”

Ruíz’s documentary connects viewers with the extraordinary men and women who risk their lives to report hard-hitting investigative stories about government and police corruption, and organized crime in Tijuana. Reportero focuses on the newspaper Zeta, which links the violence against journalists to the censorship and repression of Mexico’s government at the time of Miranda’s murder, and makes a compelling case that Mexico’s political and legal systems are complicit in the slaying of journalists by allowing their killers to get away with complete impunity.

Back in 1988, Miranda was the latest victim in a decade that had claimed the lives of over 30 journalists in Mexico who had been covering drug trafficking, government corruption, and questionable police practices. Reportero compels viewers to see the pain and indignity of these journalists through the unfiltered testimonies of Zeta editors and reporters who have become targets.

Miranda was the first Zeta journalist killed, but despite public outcry, it took five years and the election of a new government before the suspect—Victoriano Medina Moreno, a 37-year-old security guard at the Agua Caliente Racetrack—was charged and arrested. The film points out that because the government made no attempt to bring the intellectual authors of Miranda’s killing to justice, Zeta still includes a page in every issue about its co-founder’s killing, exposing the Tijuana millionaire Jorge Hank Rhon—owner of the racetrack and employer of Moreno—as one of the suspected masterminds. “Why did one of your bodyguards kill me?” the full-page spread asks of Rhon.

Other media sources support Zeta’s quest for justice and reveal how the killing of journalists like Miranda are still being committed with impunity. In 2012, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 64 journalists and media-related workers have been killed in Mexico since 1992, 39 of them since President Felipe Calderón came to power in 2006 and launched a government offensive against Mexico’s powerful drug cartels. The killers of 22 of the victims cited in the report have never been brought to justice.

Ruíz’s documentary chronicles how this collapse of Mexican government and legal institutions that failed to uphold public interest compelled some journalists to establish independent newspapers like Zeta. The newspaper’s co-director, Adela Navarro, says early in the film that when the weekly was established in 1980, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) made it impossible to publish articles critical of the government. As a result, she explaines, the only way to practice investigative journalism was to “found a newspaper that belonged to journalists, independent from corporate, union, or political interests.”

The documentary uses archival film footage from an interview with the weekly’s co-director Jesús Blancornelas before his death in 2006 to drive this point even further by explaining how various affiliations undermine public interest. “The newspapers have always been controlled by businessmen or politicians,” he says, “and when I worked for them, I couldn’t write what I saw. I don’t mean my own opinions, but what I witnessed with my own eyes.”

Blancornelas’s career before Zeta is briefly mentioned, but the film makes it clear that his unbending standard to report the truth made him, along with Miranda, the target of government censorship and repression as early as the late 1970s. Other news accounts document how before Zeta, Blancornelas had launched the Tijuana newspaper Adelante Baja California (ABC) in 1977. After standing up to demands from the state’s governor, Roberto de la Madrid, to fire Miranda—whose columns were highly critical of the governor and local politicians—the state government sent police to forcibly seize control of the publication under the pretext of a labor dispute. Blancornelas would have to exile himself to the United States for two years until the Mexican government dropped charges that accused him of fraud in ABC.

After the collapse of ABC, Blancornelas and Miranda decided to found another newspaper and after they briefly considered calling the new publication DEF, following the next three letters after ABC, they decided to jump to the end of the alphabet to Zeta as a clear statement that they would never let the government silence them again.

Reportero explains how Zeta was founded during Blancornelas’s exile in San Diego, California, in 1980. Viewers can appreciate through the testimony of Blancornela’s son René Blanco, the current co-director of Zeta, how the weekly grew from a small network of family and friends on both sides of the U.S.-Mexican border. “The only link between the newspaper and my father was my mother,” recalls Blanco in the film. “She would take the original pages across the border for him to edit. Sometimes she crossed two or three times a day.”

Both Blancornelas and Mirandas’s zeal to protect Zeta’s freedom of speech also compelled them to print the weekly in California, outside of the Mexican government’s influence, which then monopolized the printing industry. “In the 1980s, PIPSA, the only company that sold paper [in Mexico], was owned by the government,” Navarro says in the film. “If they liked what you wrote, they’d sell you paper. If they didn’t, you wouldn’t get any.” Zeta continues to print in California in an effort to maintain its autonomy. “It’s more expensive to print in the U.S. Each time the peso devaluates against the dollar, it weakens us. But it guarantees our freedom of expression,” Navarro further explains.

Today, with a circulation of about 30,000, Zeta is an anomaly in comparison with most newspapers, which rely heavily on the Internet. Reportero shows viewers how the weekly depends more on a human network of distribution that in some ways has become like an extended family that maintains the legacy of the Blancornelas-Miranda partnership. Every Friday at 4 a.m., bundles of the thick weekly are hauled over the border to Mexico in trucks that are branded with Zeta’s motto, Libre como el viento (Free like the wind) and distributed by hundreds of street vendors. Zeta then posts its stories on the Web three days later with a focus on drawing readers to the print edition instead of “replacing it.”

As Ruíz’s film penetrates deeper into Zeta’s 32-year history, it also asks viewers to consider what newspapers reflect about them as readers—why do we read what we read, and how does our interest gauge the success and failure of a newspaper? Recent sales show how the interest of Zeta’s readership has shifted from the political and social pieces that were the centerpiece of the weekly’s content to drug-trafficking and organized-crime stories.

“When we publish a political story on our front page,” says Blanco, “it doesn’t sell as well as a narco story. If it were up to the newspaper vendors, the paper would be dripping blood.” This perspective reflects a wider trend in the Mexican media, which has prioritized stories of drug-war executions, gun battles, and masked soldiers on the streets over important social issues that focus on political reform and the protection of civil rights.

This is particularly disheartening for Zeta reporters who do not want to desensitize their readers with chronicles of gratuitous violence. The newspaper seeks alternatively to bring readers closer to the families and neighborhoods of the victims. But when these journalists are also threatened by organized crime, they have to dig deep to recover the human connection that compels them to write.

At the end of the film, one of Zeta’s journalists, Sergio Haro Cordero, who has received death threats for his drug war reporting, personifies the moral dilemma that many investigative journalists in Mexico are confronted with daily. Is it worth risking my life to cover a story? Could I just look away? The viewer can hear the weight of Haro’s moral conviction in his voice as he concludes that not reporting on drug violence would betray the legacy of Blancornelas and Miranda, and would make him just another accomplice.

Arturo Conde is the former director of NACLA and a freelance journalist. He covers immigration rights, Latino issues, bilingual education, and culture. His articles appear in Univision News, City Limits, the Spanish newspaper La Opinión, and other publications.

Read the rest of NACLA's Fall 2012 issue: "#Radical Media: Communication Unbound."