First impressions matter and diablos rojos (“red devil”) buses make bold introductions. A riot of colors and images streaks down the street with booming bass and flashing lights. Everyone looks up when a diablo passes. After clambering up metal stairs, passengers are immediately hypnotized by a giant flatscreen blasting the latest Veejay mixes. The bus’s crisp leather seats are cool to the touch and merciful to a languid body melting in the Panamanian heat. The engine emits a bestial roar. Amid government efforts to modernize Panama City, diablos face the risk of being phased out and fully decommissioned. Some local residents, however, remain staunch defenders of these iconic buses.

Like many things in Panama, this story starts with the Canal. One of the most complicated infrastructure projects in human history, it carved a 50-mile maritime highway uphill and downhill through a malarial rainforest. In 1903, Panama declared its independence from Colombia and the United States took control over canal construction, importing vehicles, tools, and workers.

Most migrant workers originated in the Anglo-Caribbean—particularly Barbados—adding a sizable English-speaking, Black population to the preexisting Hispanic-mestizo country. Chinese, Indians, Arabs, Europeans, and Americans all flocked to the capital, converting a provincial city into a cosmopolitan metropolis. Political and intellectual elites (la ciudad letrada) lamented the loss of their idealized Panama—a land of pueblitos punctuated with festivals. For them, panameñidad was Spanish-descended settlers raising cattle and working the land. The Azuero peninsula epitomized this romanticized heartland. The corridor along the canal transformed into something different—urban, outward-looking, and commercial. Its beating heart has one name—la Ciudad.

As Panama City’s population surged, minibuses replaced the tranvía (tram). Called chivas, the first minibuses were converted Chevrolet or Chrysler pickups with wooden boards, holding eight to twelve passengers. The cramped design meant riders faced each other while boleros or mambos lilted and swaggered in the background. Low ceilings and plentiful knees in the aisle meant riders were adept contortionists. By forcing proximity and eye contact, buses were social hotspots with freely exchanged gossip, fashion statements, and arguments about baseball and politics. The bus became a place and experience in its own right—not an ephemeral bookend between activities.

Diablos rojos—school buses manufactured by U.S. companies International and Bluebird—entered the scene in the 1970s. Unlike their predecessors, diablos carried more passengers in greater comfort. Their higher clearance complemented the rutted, potholed streets of the city and outlying neighborhoods. But these buses were secondhand, with a decade’s experience of ferrying boisterous U.S. schoolchildren. They were cheap and durable, but needed a makeover. They would also benefit from a new political order.

In 1968, a military coup against then-president Arnulfo Arias upended the status quo. Arias typified the old Panamanian elite; born to a relatively affluent, landowning family in the interior, he studied in the United States and assumed the Presidency on three separate occasions. A proud nationalist, Arias promoted a “Panama for Panamanians.” While this stance generated conflict with the United States—which controlled the Canal Zone—the phrase underlined a problematic racial ideology. In an op-ed, he penned: “We fear a black cloud of English speakers occupying our city…our people crave measures to stop racial degeneration—minimally, creating obstacles against the entry of parasitic races” (italics added).

He clarified, “parasitic” races included Chinese, Japanese, Syrians, Turks, Indians, and Blacks. In the Presidency, he advocated eugenics-bile, introduced an immigration ban, and revoked citizenship for many, particularly Anglo-speaking Blacks. He confiscated shops and instigated xenophobic violence against immigrant merchants. Despite some popular reforms, his dictatorial inclinations and corruption triggered popular unrest. With three separate terms in office, he never lasted two years before being overthrown.

Through the 1968 coup, Lieutenant Colonel Omar Torrijos seized and consolidated power. He adopted a “man of the people” persona, called himself a “dictator with a heart”, and held titles such as “Chief of the Government” and “Maximum Leader of the Revolution.” He pursued agrarian reform and pro-labor policies, while building schools and hospitals. To most Panamanians, he is remembered for negotiating the treaty with Jimmy Carter that eventually returned the Canal to Panamanian control.

During a 1973 bus strike, Torrijos embarked on a radical reform. He feared a cartel of families who ran the city bus routes. They were political opponents linked to Arias and Torrijos worried they would undermine his government. Consequently, he abolished the family-run companies and permitted independent operators. Individuals could import buses, run routes, and form associations Driving a bus became an attractive blue-collar gig: dignified, with personal autonomy and decent pay. But opening the floodgates to participation meant drivers competed fiercely for customers—they needed to show up and stand out.

Enter the Era of “Prity”

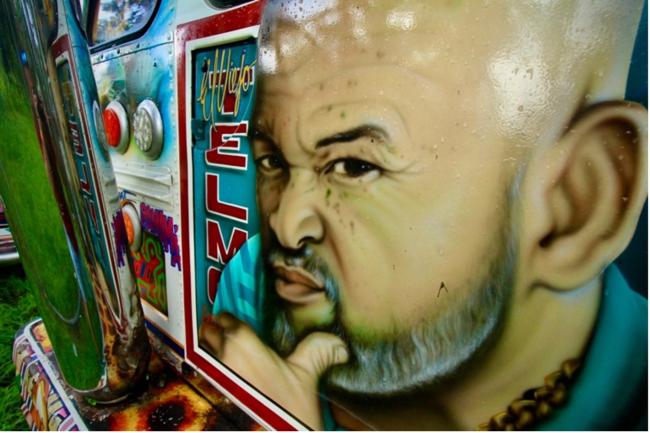

A generic, beat-up school bus fails to impress and drivers modified their buses to make them "prity" (pretty). While chivas included artistic embellishments, diablos rojos became an art form. Peter Szok’s book Wolf Tracks beautifully recounts how this popular art developed in poor, Black neighborhoods. Pioneers like Luis “El Lobo” Evans painted chivas in the 1940s and his style influenced early diablo artists: Teodoro “Yoyo” de Jesús Villarué, Ramón “Monchi” Enrique Hormi, and later, Andrés Salazar.

Buses became arte rodante, rolling art installations splattered with geometric patterns, cartoons, images, and pregones (catchy phrases), festooned with leather fringes, and kitted in chrome and flashing lights. Every bus is unique and has a name. Chat with a bus owner and they swell with pride, as if they are describing cherished family members. Drivers assume the role of tastemaker and DJ, sharing personally-curated tracklists—devotional, morning baladas transitioning to bachata, salsa, and reggaetón in the afternoon. The back door is a revered canvas featuring famous singers, politicians, actors, and sports stars. Frequently, one sees spouses, lovers, children, and relatives. Commoners are elevated to celebrity status.

The cogent argument threading Szok’s book is that bus art asserted the artist’s—and by extension, the driver’s—sense of self and value in a society that consistently denigrated and erased Afro-culture as “un-Panamanian.” Bus art is popular art—cultural elites devalued and demeaned it for decades. Scolded as ostentatious, artists and drivers stood out to become visible. They refused to accept undifferentiated anonymity. The bus confidently proclaimed the individual in a very public space. Not buried in private galleries or museums, bus art is literally street art.

![Cristóbal “Piri” Merszthal said: “I put myself in every bus [trying to] put my best self out there. Painting buses captures you and marks you for life... It makes you proud. Starting from zero, you make everything and it’s a rebirth.”](https://nacla.org/sites/default/files/styles/650px_wide/public/DiablosRojos_8.jpg?itok=R_Rk1unU)

![Oscar Melgar said: “You entered the bus, hearing [Rubén Blades, Héctor Lavoe]… you started chatting with the stranger next to you. Then, you lost yourself in the art, ultimately, falling in love with your daily commute.”](https://nacla.org/sites/default/files/styles/650px_wide/public/DiablosRojos_9.jpg?itok=_HBVzFec)

Artists built careers, putting their visions on the rolling canvas. Neighborhoods rallied around their bus with its unique images, sounds, and pregones. Locals admitted to waiting for their favorite bus, even if it meant turning down the bus parked in front of them. Drivers were known entities, recognized throughout the community. Diablos became expressions of individual and collective identity nailed into the concrete fabric of urban folklore. Driver Telmo Antonio Julio Sr. said it directly. “You look at a diablo and it’s practically a Panamanian flag. I love it like my sons. This is familial patrimony.”

A new ecosystem flourished. Secretaries (pavos) call out the route, take money, and help drivers navigate narrow spots. Mechanics perform Herculean tasks, keeping trundling warriors operable despite few spare parts. Metal workers craft custom grills, rims, and exhaust systems with horns that could stop boats. Electricians soup up audio-visual systems with massive batteries. Leatherworkers re-upholster seats. Several drivers revealed they invested upwards of $30,000 USD. To them, expenses were investments—the price for individual freedom and independence. They could be their own boss, dressing like they want and driving when they want. Fathers and uncles impart skillsets and buses to their children. New initiates start at the bottom, washing buses—dreaming one day of becoming drivers and owners.

Omar, an Uber driver, is nostalgic. His kids will never know the real diablo experience. He left the San Miguelito neighborhood in Panama City and now, no diablos cruise his block. “It was cool, loud, brash, you could meet chicas and the best ones took the coolest buses.” His first kiss was in the backseat of a Diablo, he confides with a chuckle. As we drive by a metrobús, Omar sighs. “Those are okay, but it’s comida sin sal.” I retort: “The diablo rojo would have sal y picante chombo!” Omar flashes a wide smile. “Definitivamente.”

At the end of 1999, the Canal was returned to Panama. No longer consumed with correcting a historical wrong, the government focused on the future. Elites envisioned a financial and logistics hub—a Singapore of the Americas. Skyscrapers and air-conditioned shopping malls shot up. In this modern Panama, there was no room for old school buses and independent, owner-operators. The diablos, harried as ever, raced around the streets searching for customers, filling their buses beyond capacity. Several headline-grabbing accidents triggered a political outcry. Why were old buses still plying the streets of this urbane metropolis? If Omar Torrijos opened the road for diablos, his son, Martín Torrijos, curbed them.

As President, Martín launched an urban mobility plan, promising to eliminate diablos. The government purchased Brazilian Marco Polo buses and recentralized urban transport in the hands of a Panamanian-Colombian consortium. The city established the Metrobús system with standardized service routes and fixed bus stops. Larger buses hauled more passengers, featuring a prepaid card system, and most importantly—air conditioning. More environmentally friendly, the new fleet belches fewer noxious fumes and carbon. Drivers were offered $25,000 to retire their diablos rojos—which were promptly scrapped for parts. For many in the diablo community, it was an ignominious end for a community icon. Many owners refused to decommission their buses. The compensation money was paltry compared to the sums invested. Furthermore, the unsentimental finale—shredding, compacting, and shipping the recyclable pieces to a foreign country—verged on blasphemy.

At the Albrook bus terminal, the counter attendant emphatically denies the lot contains any diablos rojos. “Those no longer exist,” she replies flatly. A glance at the lot undermines that argument. We pay our 25 cents entrance fee and make a beeline for the flashiest diablo resting in a corner. Security guards quickly materialize to badger us. “What are we doing here?”

Despite a significant overhaul, the Metrobús rollout experienced growing pains and fell short of expectations. A decade later, diablos and independent operators remain, but routes are severely diminished, largely connecting Albrook to the city’s poor communities on the periphery. A few drivers ditched their diablos for “neveras” (refrigerators)—newer Hyundais and Mini-Toyota Coasters with air-conditioning and minimal ornamentation. Nevertheless, independent operators continue supplying routes the Metrobús cannot or will not service.

Metrobús critics note there are too few buses to provide reliable, efficient service to all neighborhoods. Where service does exist, announced schedules are rarely accurate. Poor-quality roads cause constant breakdowns. New buses have neither the clearance nor durability of their diablo predecessors. While buses are clean, service can be surly and the hard plastic seats leave you saddle-sore. Many buses are still not wheelchair accessible. Commuters—earbuds firmly fixed—stare forlornly at their phones. No one recognizes or converses with the driver. There are no vendors or music. Buses have numbers, not names. Their colorless façades no longer represent neighborhoods or elicit much attachment. A brooding sense of loneliness and fatigue pervades.

Celebrated by politicians and technocrats, this eminently modern system of transportation embraces a sterile homogeneity. Lisbon had nearly identical buses—down to the orange-white paint scheme. Metrobús appeals to our sensibility for increased safety and efficiency, but something meaningful is being lost. To those in the diablo community, it feels like an imposition. For Oscar, striking diablos from the cultural landscape is akin to moving the Panama Canal to Nicaragua, getting rid of polleras (a traditional women’s dress), or killing off the endangered Golden Tree Frog. It is gutting. He notes the irony of the government promoting diablos rojos on tourist fliers while simultaneously eliminating them from quotidian life. No official asks Oscar or Piri to paint a metrobús—the goal is emulating international models, not celebrating Panamanian idiosyncrasies.

In 2014, then-president Ricardo Martinelli opened the Metro—Central America’s only subway system. A fierce critic of diablos, Martinelli’s polemic term witnessed significant infrastructure spending, including an expansion of the Canal. He was leading polls for the upcoming May election and promised to fully eliminate Diablos, but criminal convictions for money laundering barred him from the competition. Currently, he is hiding inside the Nicaraguan embassy.

Despite Martinelli’s disqualification, his Metro expands. A new line will connect the working-class, commuter towns of Panamá Oeste to Albrook by 2026. Estimated at nearly $3 billion, Línea 3 includes a tunnel under the Canal. It promises greater convenience, speed, and affordability. Service will finally reach poor communities that depend heavily on public transportation. But what about the diablos?

For two decades, politicians and observers predicted their demise—yet diablos persist. A gentleman awaiting his bus in Arraiján is steadfast. Metro stations will change routes, but Diablos are not going anywhere. They mean too much to the community. Somehow old U.S. school buses—legacies of American imperialism—were transformed into symbols of Panamanian popular culture. City planners remain unmoved.

Piri stares wistfully at the sky. A day when there are no longer diablos rojos? “That will be like a garden without roses. A sky without stars.”

All images in this article are courtesy of Grant Burier and Sarah Saeed.

Grant Burier is a political scientist and Associate Professor at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He currently co-directs the Panama Project Center. He researches infrastructure, development, and the environment throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. You can find more articles on Muckrack and ResearchGate.

Sarah Saeed is a Civil Engineering student at Worcester Polytechnic Institute with a minor in Philosophy and Religion. Their writing focuses on culture and identity.